Walking through Stanstead at 5.27am one morning, bleary-eyed and dehydrated, I surveyed the carnage around me. Men bent-double over pints of lager, a girl with sad eyes and bad makeup offering samples of skin cream to nobody, a four year old with hair the colour of maple leaves lost in the drone of wheelie suitcases clutching the straps of her pink backpack, so overwhelmed by the amount of human energy on show I wanted to pick her up and run. Why do people go on holiday I thought.

What are they escaping from.

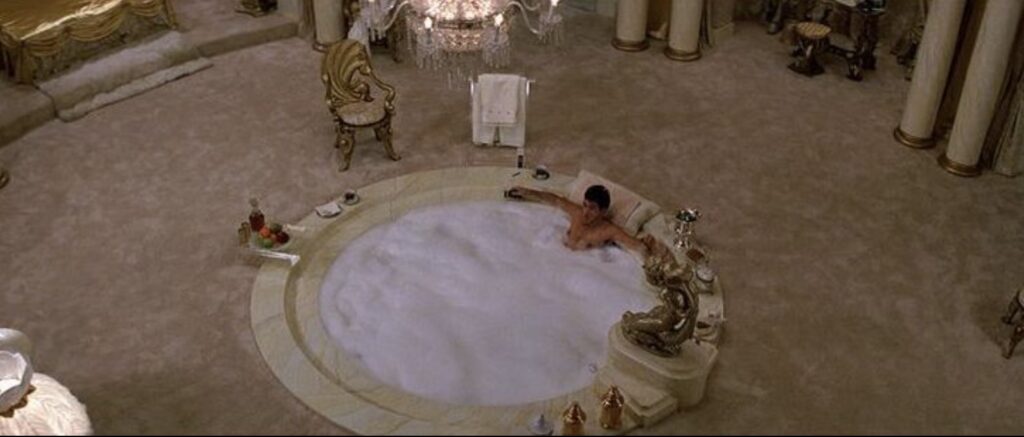

It isn’t until about two days into my holiday, a few years later, sitting on soft cushions heated by the sun, experiencing DFS-advert comfort as the soup of hot air from the Sirocco pushes salt and the barking of dogs and some sentences in dialect towards me, and I stare out at the expanse of water and mull over a beer, an extremely cold beer, a Messina Cristalli Di Sale, and imagine the taste of the first sip fizzing and cooling my mouth, it isn’t until then that it dawns on me something I don’t think about very much, that a holiday can be a monumental experience, because this is fantastic.

I walk languidly from the terrace into the dark cool of the kitchen and take a bottle from the fridge, I crack it and hit it, it does more than my imagination had prepared me for. If someone handed me a pale ale from some microbrewery in Clapton right now I’d throw it at their forehead and insult their career trajectory. This is the beer for me. I am an islander now. One of the Filicudari.

The mountain in the middle of the sea they call it. A mass of volcanic rock rising out of the Tyrrhenian to the north east of Sicily, Filicudi is one of the 7 Isole Eolie ruled over in myth by Aeolus the divine keeper of the winds, who Homer told, helped Odysseus on his way by granting him a favourable gust. An island far from war, far from time, watched over by the sun, wrote Roland Zoss in 1973. The same sun watches over me. I look out over the water from my heated cushion and raise the bottle and toast.

It heats up quickly and I drink it fast, record-trouncing temperatures are igniting hillsides across the Mediterranean, Syracuse records 48 degrees on Wednesday, the Italians are too refined for stubby holders. Thousands emigrated to Australia from these islands between the wars, one of them could’ve brought a stubby holder back by now. The drink of the Filicudari is Malvasia, a sweet straw wine grown on the vines of Lipari.

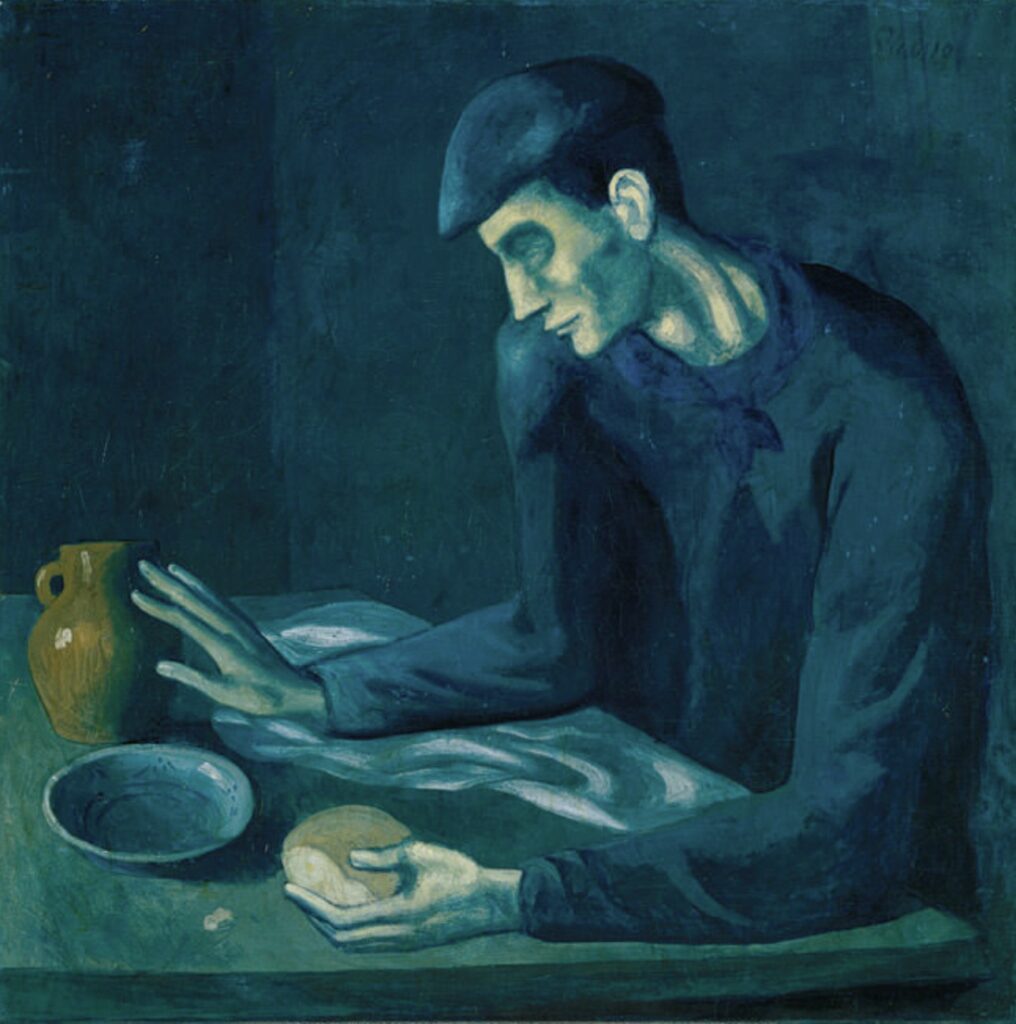

Two days before I spent the morning in bed, overwhelmed by my new environment. Was it too long in lockdown, was it my old age, was I hormonal, bed seemed safer, I wasn’t ready for this strange world outside the window. I woke at eight but stayed put til eleven, hiding under sheets, until a grudging acceptance came that spending a week there would be a bad use of my time. I ventured out. Cool dark high-ceilinged rooms, sheathes of light, through a doorway a slender ankle.

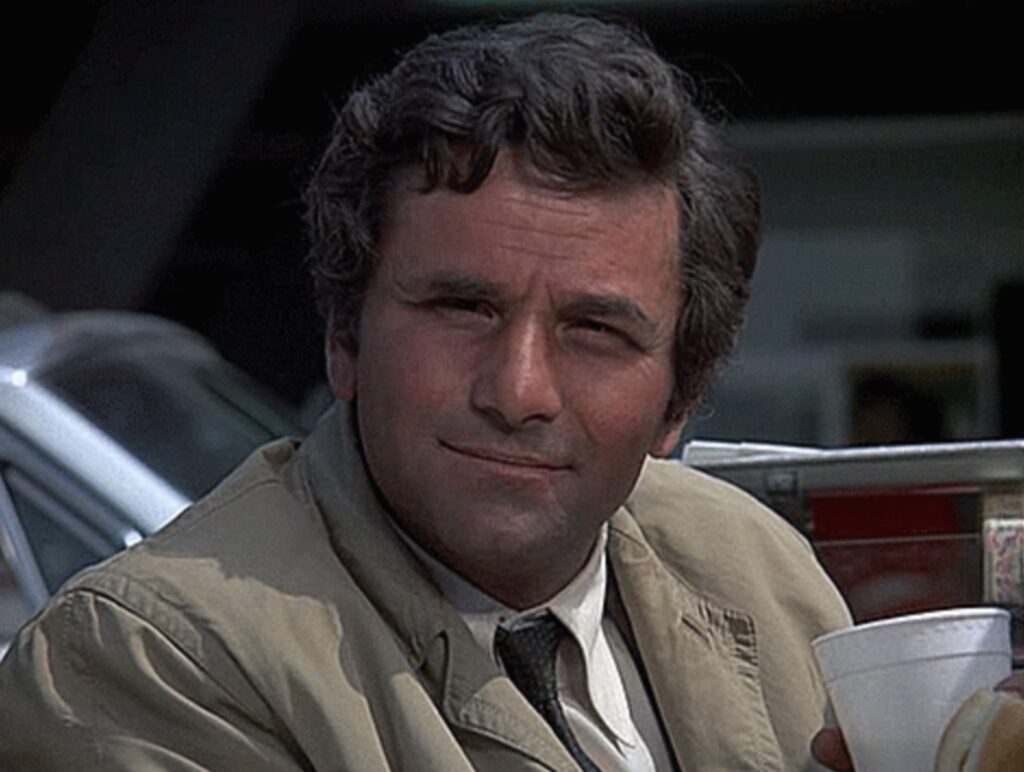

Raymond is a man of class and continental allure. The incarnation of a sea breeze, inhabiter of past lives, he keeps a fine collection of linen shirts and an Amex open to new experience. On the phone across the ocean to plumbers, electricians, plasterers, stone-cutters, painters, engineers and foremen he speaks of mastic, light-switches, second coats, architraves, shower handles, Sky installation, and dust. His mother calls and he reassures her that move-in day is imminent. Mate if I did even one of those things in a calendar year for my parents they’d never recover. It’s a cultural thing bro, he explains, children look after their parents in India, it’s expected.

One of the nice things about being with people our age is studying how they’ve set up their lives, taking the things you admire and using them for inspiration. Most of all I dig Raymond’s adventure. Every year he spends months in different continents making new friends of all ages and creeds. I think how much new experience this gives him, how good to break habit and repetition and I am envious. I feel boring, it makes me want to be braver, to go and see new things. This adventure had led him, by word of mouth, to rent a villa on Filicudi for a month, most islanders we meet gawp and exclaim wat aryu doin eyur in Filicudi!

I feel like a celebrity groupie.

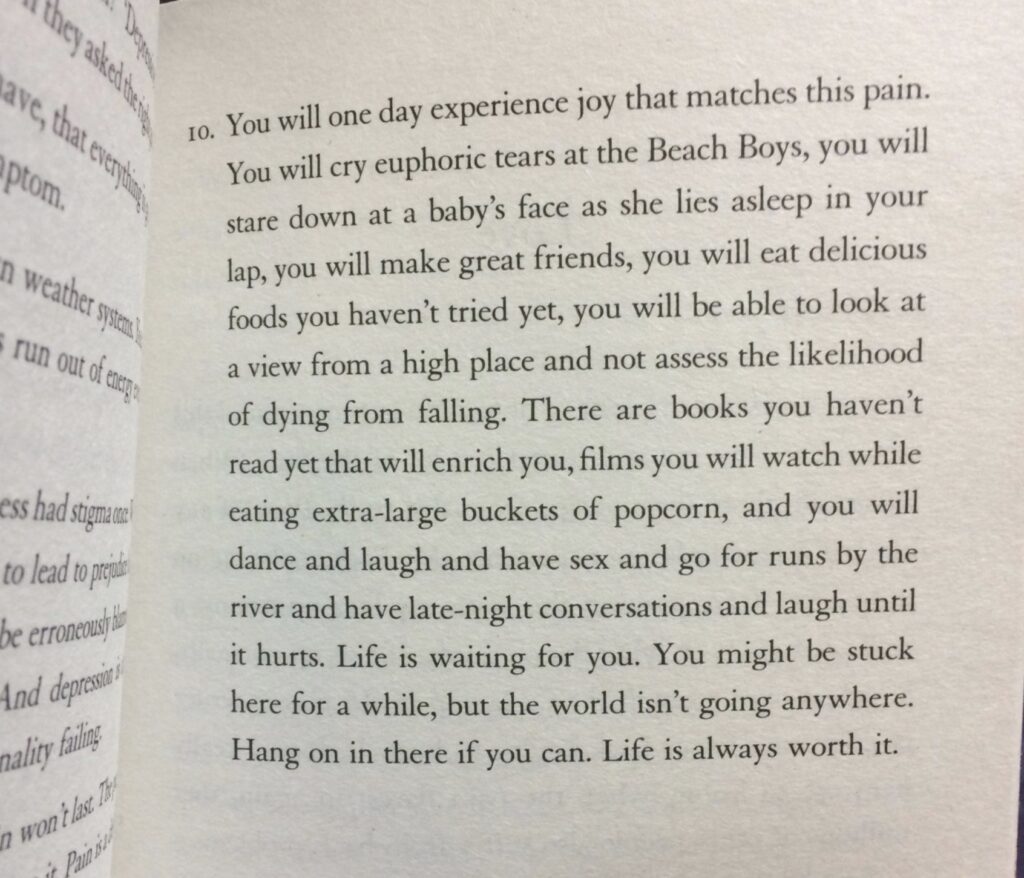

We go and swim and the big boulders of the Tyrrhenian are smooth and slick and comforting, the water is warm and the salt is tasty and I starfish on the surface and try to zoom out and imagine this strange spot in the endless ocean and I think wow what the hell where am I. And then a strong understanding of how much my brain needed reminding, of things outside London and lockdown and the repetition of days and unlearning love, and this reality I had begun to unquestion, now floating in the sea, warm and content, was jogging my mind from, and I didn’t know how much I needed it til then.

We lunch at Gramd Hotel Sirena, spadina, tono, patate al forno, caponata, the sea salt coats my skin, panna cotta, espresso, Raymond points out the waitress. There’s something about her, he says. I look and there is. Back up to the villa, one by one we take on the steep and endless steps that climb the hill and drench us in sweat. The heat of the afternoon demands focus on nothing, I read the Neapolitan novels, a present from my cousin Clara, watch out, she says, they’re like crack, once you start you won’t stop.

At night we walk down to the port. Esta que arde like papa always says. The place is full of human energy, young and beautiful Italians, loud, gesticulating, music and cries, smoke, the sound of beer bottles against stone, queues leading to a stall selling fritti, the fading light and out to sea the boats that Raymond says have tripled in number wait. I feel nervous and awkward. I find any communication hard and am sensitive to even the mildest input. It was like this when I was small, I remember, an urgency to run from uncomfortable situations, to be alone. I don’t know why I feel it now again.

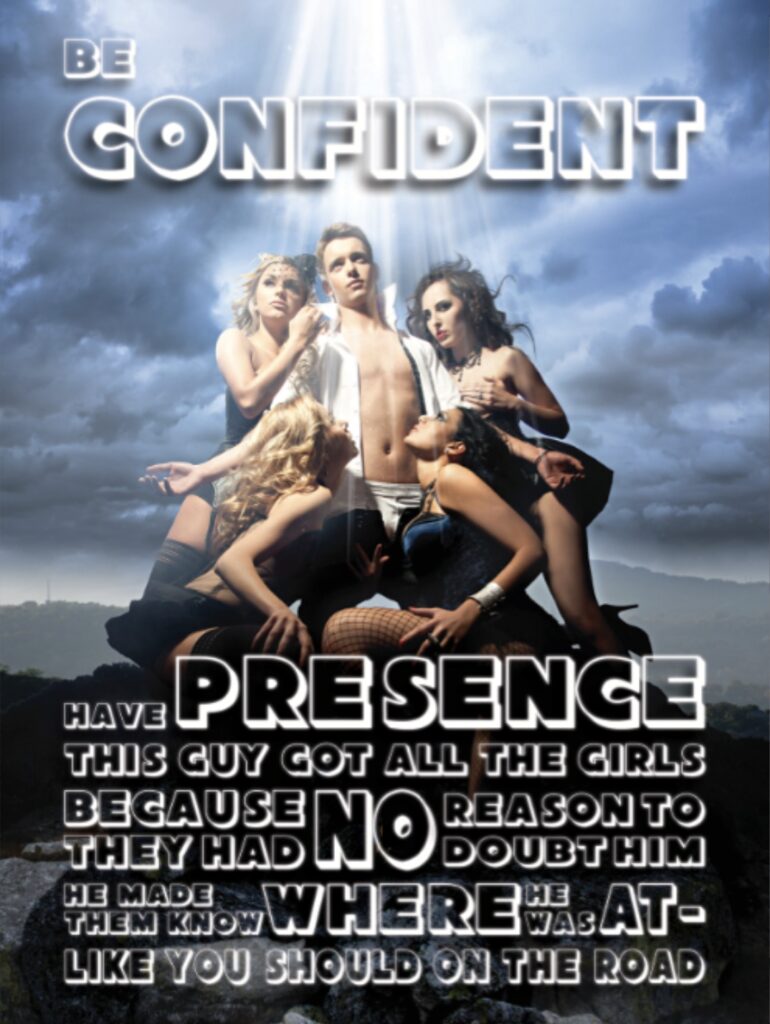

Raymond is an absolute babe magnet.

Some girl beelines towards him on the port and her friend drags her back by the hair. The guy who rents him a boat wants to take him to dinner. The mother and daughter who run the only shop in town giggle as he picks cheeses from the counter. It comes naturally to me man… he shrugs smilingly. A lady stops him in the street. She asks in shock… ma sei tu Rajan? A day later we are on her boat. Her husband Rino captains it with a tired, kind smile and two Italian women lie on the white seats, we swim off the rocks, eat lentils and drink wine, our host persuades Raymond to buy a house on the hill, it’s for sale, she will take him round it tomorrow.

The very top of the island is Fossa delle Felci, says Patricia. It is a beautiful walk. Back on the terrace I inspect my back, it is the colour of a Puglian tomato. Gisella, an islander, is doing her weekly clean. Roh-ger? She says. Rah-jan. I teach her the annunciation. An Indian name, I explain. Si Indio. Sempre con el telefonino. I ask her the name of the little purple flowers, to which she replies Bougainvillea. Bellisima ma fragile, she says looking down a little sadly at the petals on the terrace floor. A little bit of wind and they all fall. I turn and show her my back. Bougainvillea I say. She laughs.

In 1971 the islanders gathered at the port carrying with them the statue of their patron saint San Bartolo, brought down the hill from the church, to set sail for neighbouring Lipari in protest at the government’s decision to exile 18 reputed Mafiosi to the island under house arrest. 270 of them, pretty much the entire population, left. Leading the Mafiosi to complain, we’d rather be in prison, at least there we’d have company.

We go back to the restaurant the next day. Alberto the manager sits at one of the tables doing numbers on a pad. He looks up at Raymond, and starts yelling. Look at this man! A face like that and never a reservation! The waitress smiles at me for the first time and I fist-pump madly under the table. The happiest I’ve been all year.

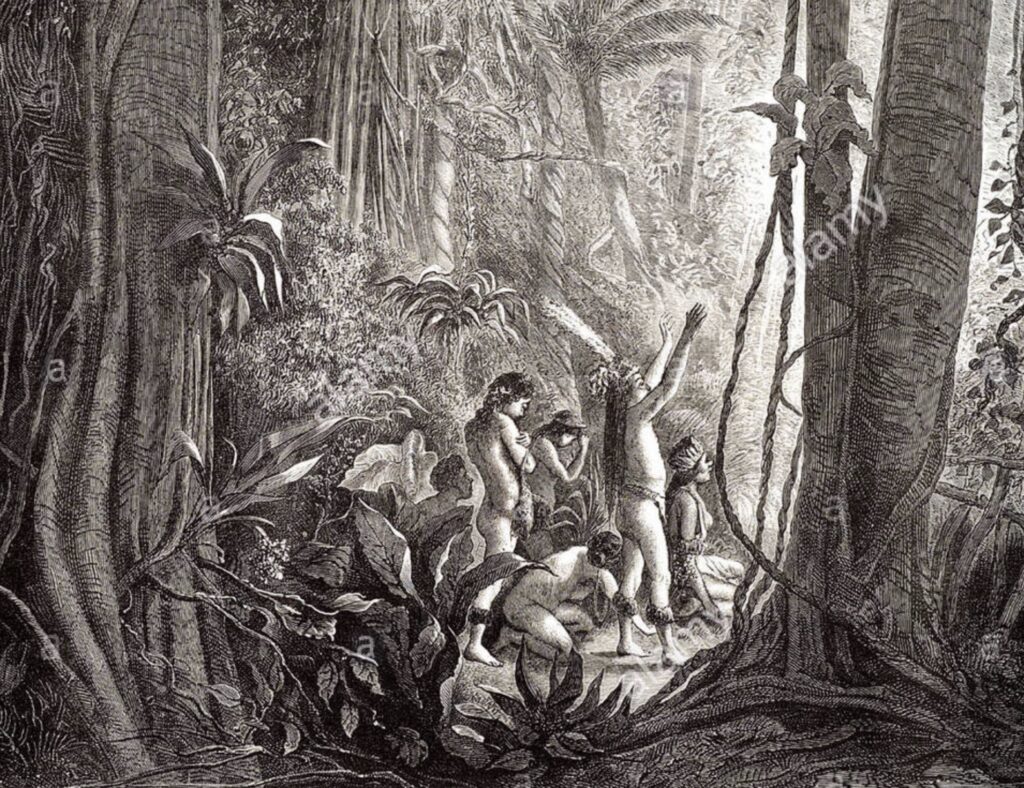

That afternoon on a bookshelf I find a map of the island’s trails. The peculiar sensitivity I’m feeling is eager for my own company, Raymond is busy with builders so I take the map and walk up into the hills. All around me I see rocks, from the shore up to the sky, terraced walls, piled up as far as the eye can see. I read in a book they are called Lenza. Torn from the mountainside, cleared of stones and levelled they were little gardens, in their thousands, where the islanders grew barley, vegetables, and fruit in the abundances the volcanic earth provided for them.

That evening we head into town spruced up and smoothed out, into the thick din of revelry, on the sloping flagstones the kids play out an unending game of football, running between the revellers spilling their drinks, politely apologising, running on. We climb the four steps to the restaurant importantly. Completo, Alberto grimaces. I smile at the waitress and she looks through me without a flicker of recognition. It took men and women hundreds of years to build the Lenza and I can’t get her attention for longer than one lunchtime, I watch her glide around the tables, bow-legged and insouciant. All of a sudden from within the kitchen the cook starts shouting. He is Gisella’s husband! Raymond will come to dinner! He will cook him whatever he desires!

Thus the week lilts onward in the manner of the boats moving around their anchor, we fall from the clutches of one day into another. We are on holiday. We swim in the sea, sleep late, drink beer with no hangover, we eat fish, read, sit in the shade, cool off in the shower. Some mornings before the sun gets too fierce I run down to the port, and glimpse the island stirring. The cacti and the cocoa-coloured earth and the wine-coloured sea.

One afternoon I walk to the cemetery. Either side of an avenue of firs the tombs bear the names of Filicudari families. Zanga, Zagami, Rando, Paina. Qui sono i resti del forte onesto e laborioso Gaetano Taranto. I look back past the gate to the sea and hear the wind rise, it moves through the trees below and comes up past the gate and a branch sways and my face just cracks.

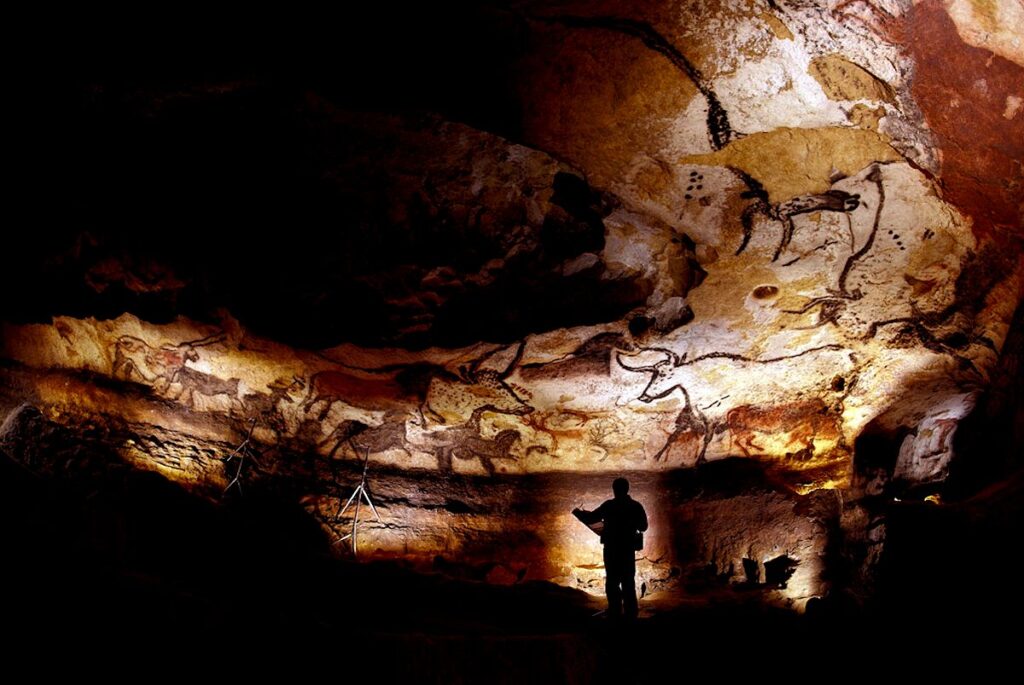

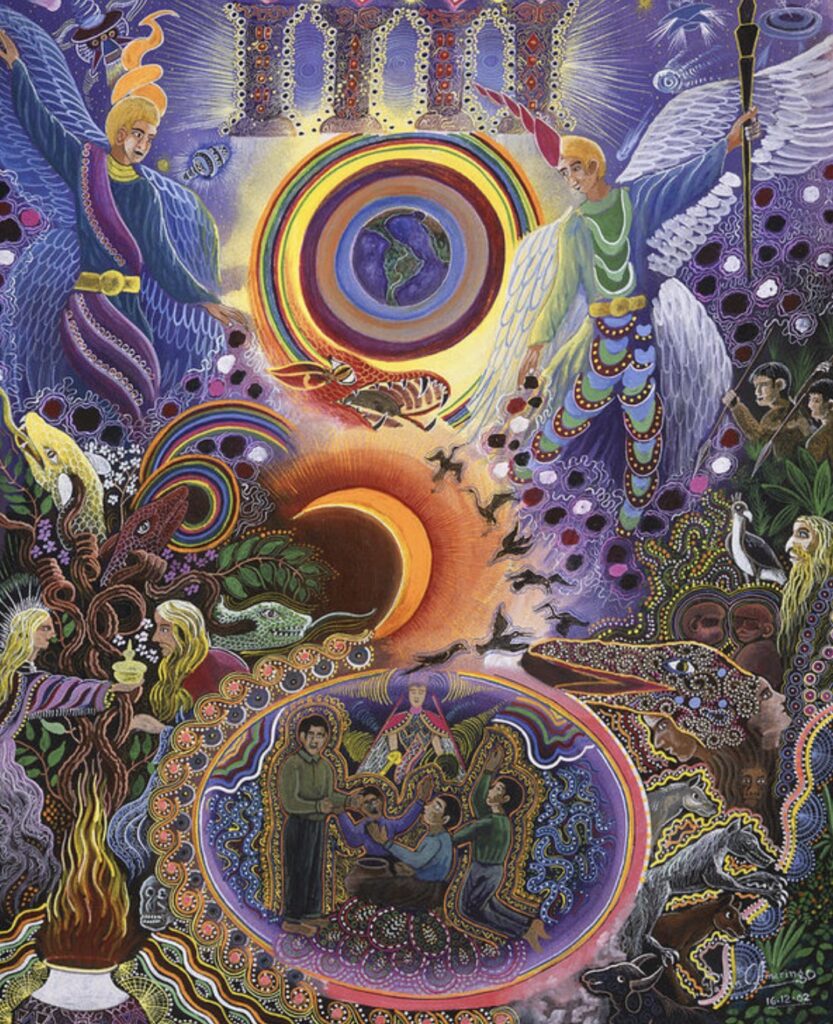

All I have been feeling lately, this overflow of senses, something like the pain of everything and our struggling on in spite of it, over and over again, and in this sacred place among generations of islanders resting here warmed by their sun and cooled by their sea, some glimpse of the endless repetition of things, the beauty despite the sorrow, a sign of what to hold onto, to be grateful for the miracle, to be involved in the grandeur. I think I have never felt so open, like I am touching the edges of something bigger and it will not always be like this so I must not let it disappear.

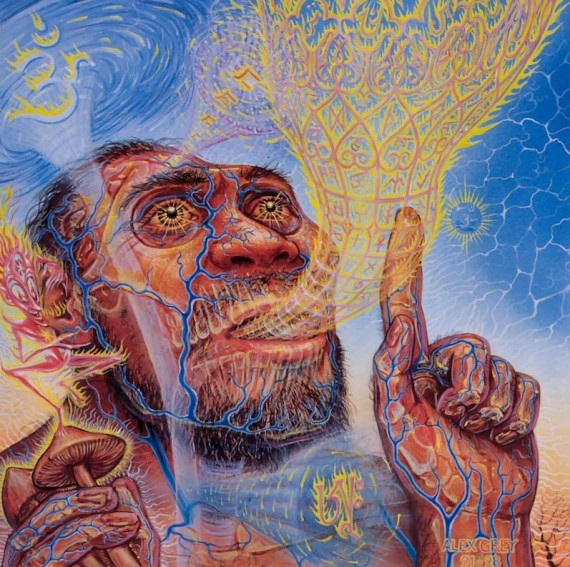

That night we eat chocolate mushrooms and listen to tunes in the dark and dance and chat breeze and end up lying on our backs on the terrace looking up at the stars, taking turns with the music. We see a dozen shooting stars at least. They leave a trail of sparks and stardust behind them. UFOs bro. Raymond laughs, tells me to shut up. Laugh all you want, one day they’ll be in charge. Probably already are. The stars are innumerable, we stare up and gawp, what a sky, what an evening, the mosquitos cut it short.

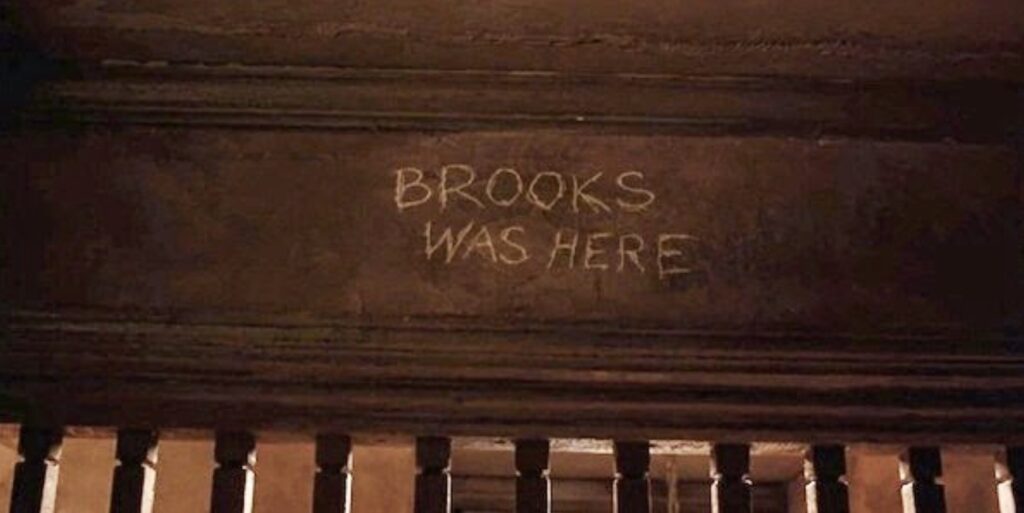

The next morning is my last and I rouse myself at six, fail in my efforts to get a slumbering Indian out of bed and pick my way up the hillside through the morning light. Up and up, along the path built from sacks of earth leftover from the building of the pier, levelled because the men carrying the statue of San Bartolo from the church would trip on uneven steps. I get above the clouds.

Over the years the children would race each other up here until the crack of a rock against one of the boulders at the summit would echo across the hillside and denote a victor. How strange and deep a week can be, even one where I don’t feel that good, I breathe in the morning, leave a little stone on top of the pile, blow a kiss to the sea and pray.

Down in the port for a last ice-cold Messina, I thank Raymond for having me, for bringing me to this strange place with his invention and his nose for new experience. I look over at the restaurant and see her. What if told her I’m leaving tomorrow, but if she goes for a drink with me I’ll stay. Pretty good opening line, no? Raymond smiles. I can’t quite work out what his smile means. A few days later, back in London I realise what it meant. Fine, said the smile, you’re never going to do it are you.

On Sunday walks down through Rotherhithe my mate Matt’s voice would boom out along the river path. It’s not a dress rehearsal! It was one of his favourites. This is it. Real life. We have to take our chances, make our luck. La oportunidad la pintan calva. Imagine, wrote Viktor Frankl, that you have lived already what you are about to do, and are aware you have done it wrong, but have a chance to go back and put it right. This, he said, is how one should live the present.

Go out into the world.

Come towards Me, said the voice.

What a way to live, I think. Still, I don’t ask her. Fear of being shot down I suppose. Not enough swagger in me. At the end of the aisle, out past the pews, the sea gets on with her business.

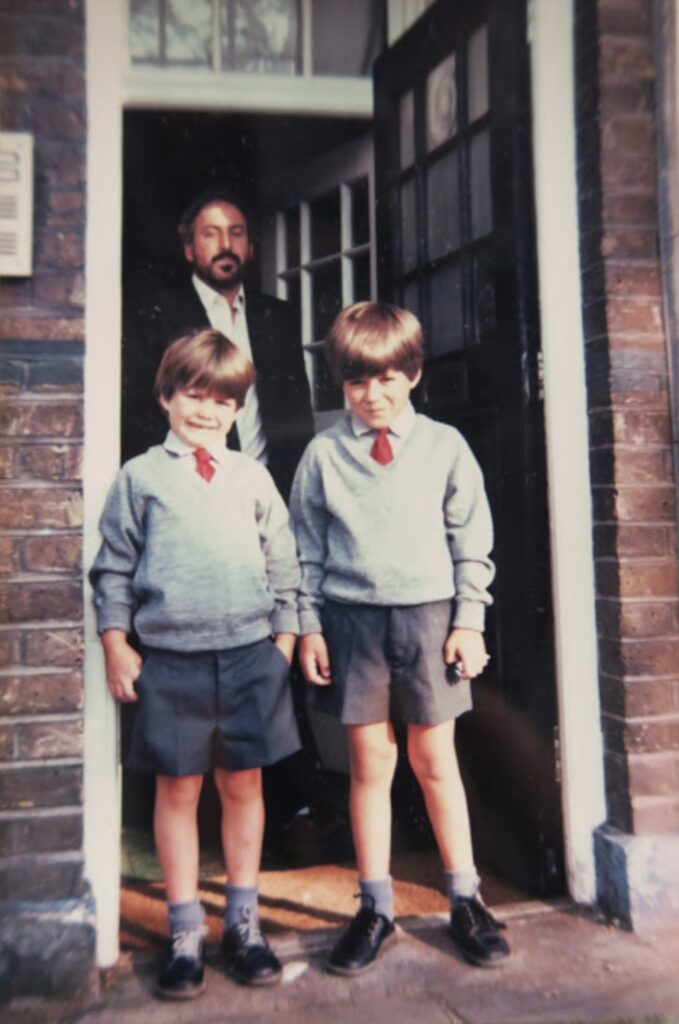

On the way back on the ferry I look through the cloudy glass at the Thyrennian, calm and with the sun on it, like silk. How long life is, I think, feeling heavy, and I must live every second of it. But it is full of an unformed magic, and all the feeling it contains I want to seek it out and write it down where I can, bottle it. The translucent skin, it callouses over, my brother tells me, sitting on the floor of his new flat. Give it some form, I think, not its perfect form, a refraction of a moment. So you can hold onto something that is always trying to leave, before it does its thing and disappears into the past.