1,268km I did, totted it up in my book.

Washed my face in the salt sea of Normandy off the ferry, saw the Med from the plane turned swamp grey by angry clouds in Marseille 12 days later. I got on a train too, which was cheating. I saw France, as always, perhaps a little differently this time. The last thing my mother said before I left was for God’s sake please don’t send any more photos of bloody croissants.

I got back filled to the brim.

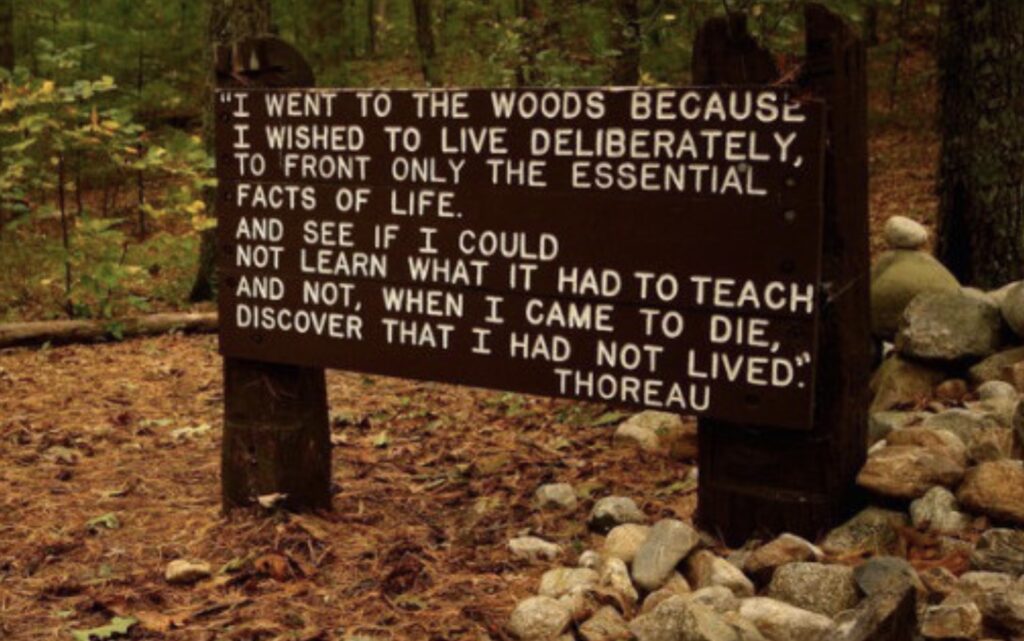

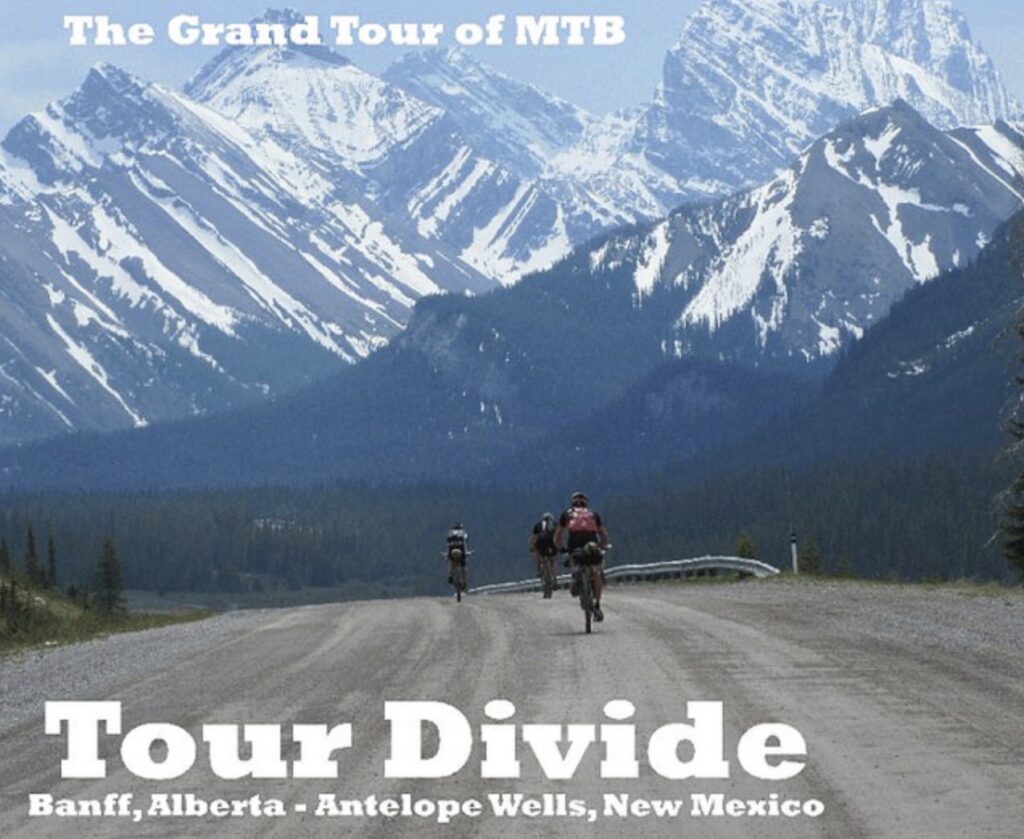

The journey did what it said on the tin. I had journeyed. Maybe more than anything I had breathed clean air for ten hours a day. And felt sun on my face. And sweated out the bad stuff. And felt alive. And scared. And stressed. And a bit brave maybe. Just getting the hell away from London was the ticket.

My old man said my mother was worried, that I always get back from these things and feel sad. But nothing of the sort. I felt supercharged. And I set to write, to stop it curdling into a soup of unmemory. And even though nothing I write would come close to bottling it, still a soupçon was better than forgetting.

For the first few days I was irritated. The townie in me resented being sat on a bike in a heat wave for eight hours a day. I felt critical, judgemental, le sandwich jambon fromage didn’t have the right amount of butter, the double café was a watery mess. A celestial beam shone through my Perrier one morning and the light on the paper had a simple message for me.

Sharpen up your shit.

I get my father’s mandatory sightseeing out of the way.

To Chartres, the famous stained glass. And I am underwhelmed, because of the people and the cleaning of the old stone which makes it look new and not real, I prefer the innumerable empty churches of villages I pass through, a tenth the size of Chartres and maybe more sacred.

I cross the Loire to Chambord, the hunting lodge built by Francis 1st, who diverted the course of a river to run past it. Never seen a building like it. The scale. Leonardo da Vinci designed a double helix staircase to run up its centre, so those ascending wouldn’t cross paths with those coming down. When the Luftwaffe bombed Paris an army of volunteers packed up all the works of art in the Louvre and in an almighty convoy took them out of the city. The halls of Chambord became their storage facility.

It riles me.

The guilt I feel for not seeing enough. Every year my old man gives me the same diatribe. What papa doesn’t get, I tell myself, is this is not cycle tourism. This isn’t swanning around the Loire to stop for a Panaché. This is crossing a landmass to dip an ankle in two oceans. This is touring. You can’t spend half a day deliberating purchases at a marché aux puces, you have to move.

It is not one cathedral’s stained glass. It is the weird villages, the cocked heads, the sleepy boulangerie queues, the cattle-bells, the bière in the late afternoon that disappears in two gulps, the vieil homme on the bench, not spoken to a soul all day, the birdsong above your tent before dawn, legs like concrete, the same bird shitting everywhere, on your tent, on your dreams, your mood like thunder, your mood calming, un petit café, one begins again.

This year I saw a France like frayed rope, where I normally see sheen I saw cracks. Hamlets of men smoking outside Tabacs muttering ‘c’est le bordel’ before going inside to bet, sad faces wheeling trolleys outside supermarkets, finely proportioned squares lined by planes missing any signs of life, ghostly whispers carried on the wind.

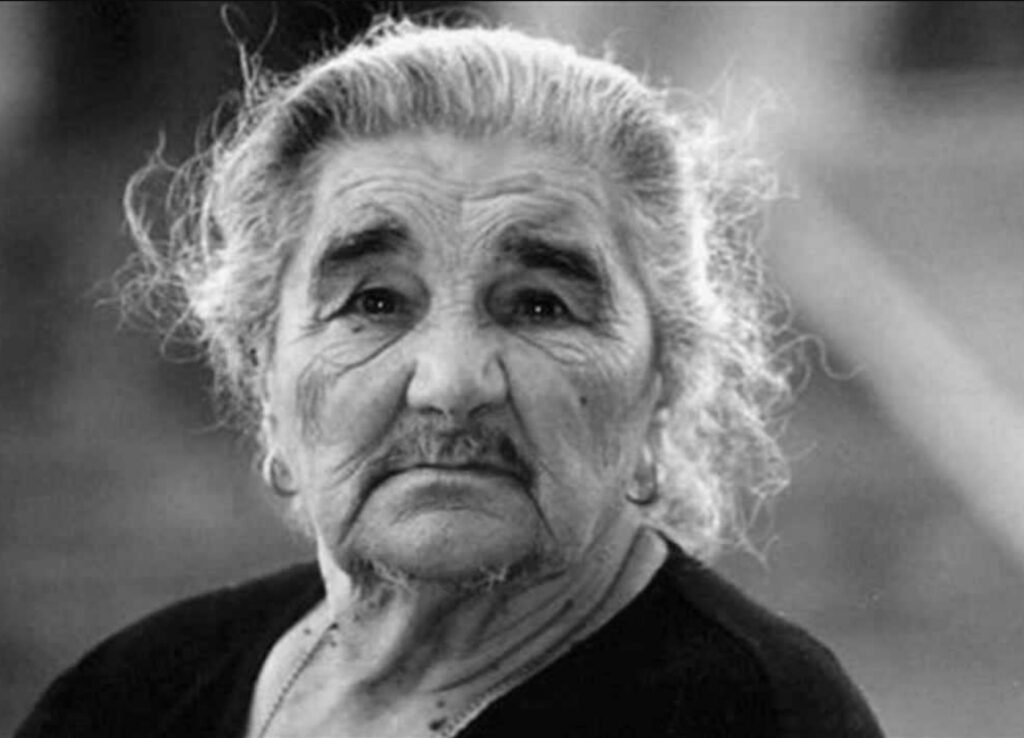

And also too the smiling faces of paysans, lined and curious, keen to know my trajectory, picking my bike up to weigh it, breaking into laughter, a lady in a service station handing me two cans of Perrier and a Powerade, declaring proudly après l’effort, le réconfort.

At Châteaudun the youths run riot and dragrace round town til 5am playing rap from car stereos and terrorise the old populace deaf to the shouts of ta gueule! That evening, sat in a snooker hall the size of a small conference centre eating Algerian lamb with four Irish Travellers in the corner trading stories, and later in bed, sleepless, hearing the screech of brakes and burning rubber, I am so happy I don’t know what to do with myself. The internet would’ve got me nowhere near this place. For ten days I go nowhere near it.

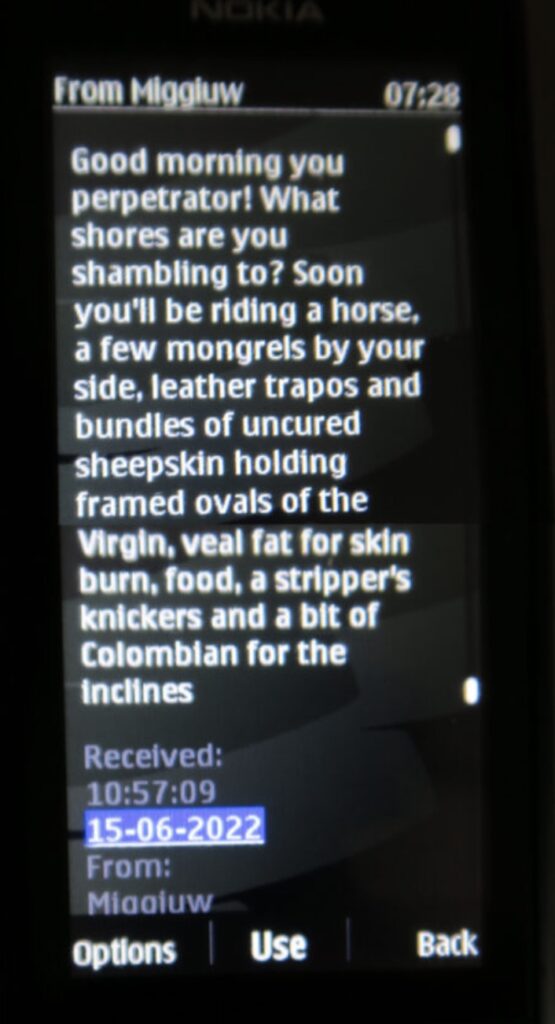

My bro texts.

A stripper’s knickers.

Bit of Colombian for the inclines.

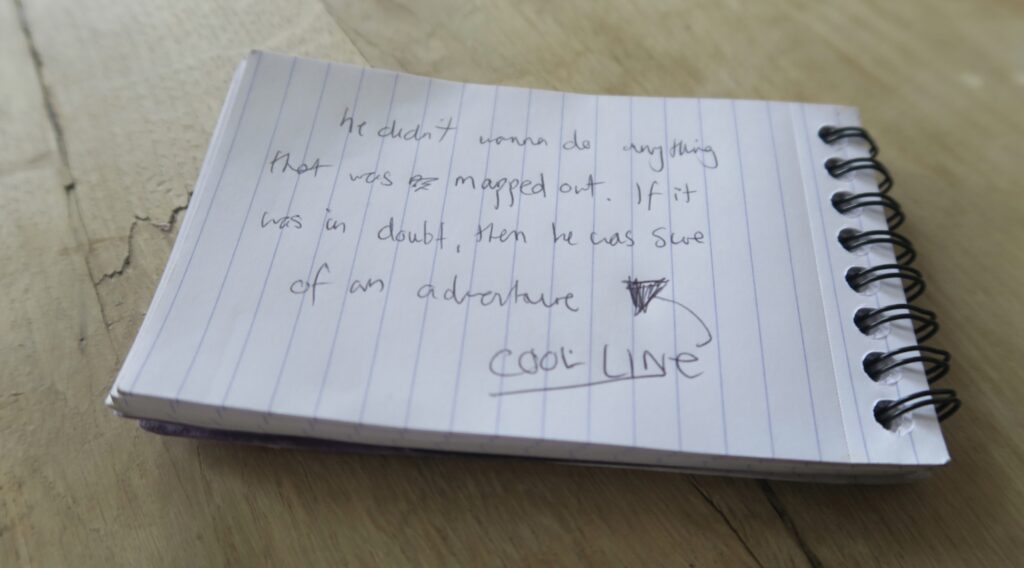

A crowd of villagers debate my route earnestly, I ask directions, get advice, I like not knowing where I’m going or where I’ll end, being untethered to the world beyond my eyes, beyond what I can see or smell or feel. Jean Baptiste fixes my rear axel at a bike shop and sends me on his favourite road, la Corniche du Drac, into the hills above Grenoble.

I camp at the bottom of a wheat field. At 1am two dogs start barking madly, I fear them leading an irate farmer to my tent, I hear a growl in the wood to my left and know I will get no sleep. I pack up all my things by the light of a head-torch, walk through the night along a road under the moon. It is warm and so quiet and I feel deep in an adventure. I sleep by the Mairie under the lights of a church and dream of large women.

For four days I am in the Hautes-Alpes. I want to see mountains Frodo, mountains. I climb all morning out of my saddle, it is ten degrees cooler at altitude than down in the valley, in and out of shadow, clawing at the gradient, getting high off the ache, I reach the top, down down down the other side. Swooping, leaning into the turns.

The ancients worshipped mountains as Gods, the clouds that cloaked the hillsides were bringers of rain, their fiery insides were the earth’s heart. I think there is nothing like being among them. Perhaps because I am never further from being found.

Cime de La Bonette is the highest road in the alps. 26km to the top takes me three hours. I am getting old. My mother is right, you’re not 25 darling, go easy on your poor legs. I make it. A loaded touring bike above 2,000 metres gets its fair share of ooh la las.

Freewheeling down the other side is…

A man at a campsite called Gilles offers me a leftover tomato from his pan and teaches me about fly-fishing for ten minutes. I return the pan, pay my compliments to the chef, he smiles, la meilleure sauce du monde, à dit ma grand-mère, c’est la faim.

There is another touring bike in the campsite. This is Kevin from Jura. His smile is something else. I’m not just here for a holiday, he says, I’m here to cure myself. What do you mean. I had an accident, cycling back drunk one evening. I hit my head, I couldn’t work for six months, I have terrible tinnitus. The longer I cycle, the more my symptoms disappear. So touring literally cures you? Yes! He breaks into laughter.

On some days, especially in the blind heat of the afternoon, when all had found shade and something in me insisted on cycling, I would get angry and would start to wonder, am I just rehashing a tired formula. Why am I still doing this. I did feel a little alone, not alone, I mean I was fine, but more like I wouldn’t mind so much sharing this with someone. Or sharing life with someone.

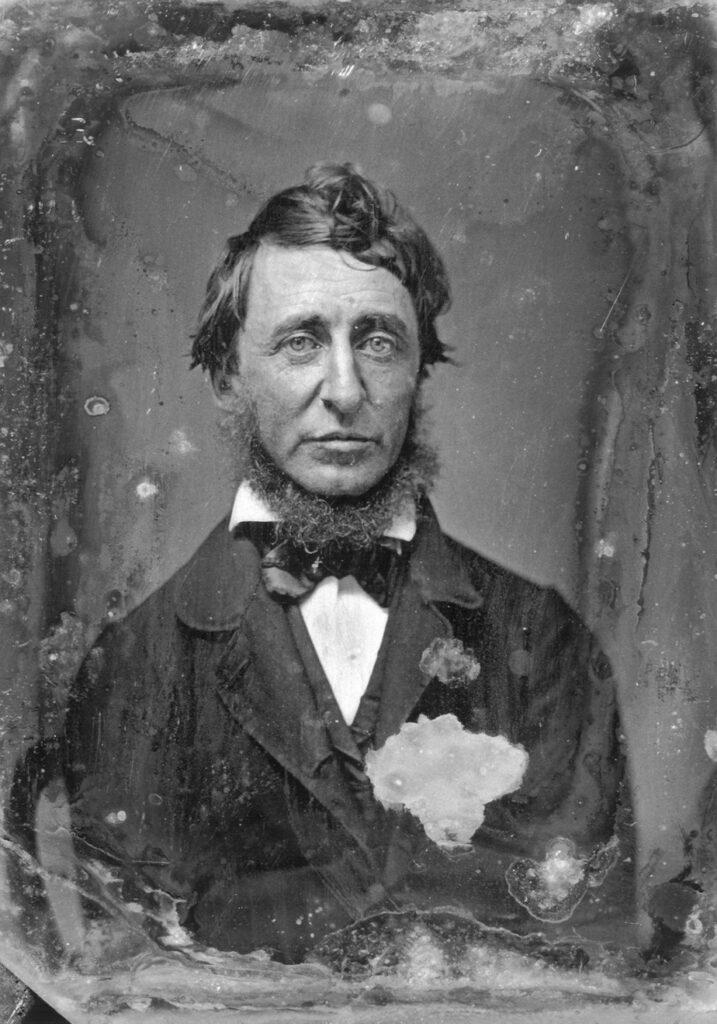

The Christopher McCandless thing.

That’s almost it.

Well not remotely, but the last thing is this.

When I’d last cycled, in autumn, up from Toulouse to the coast, I’d been in a state of openness. And spent most of my time crying. Not from sadness, just overwhelmed by the marvel of things. Everything I saw seemed to be bursting with resonance. Looking out to sea was looking aeons into the past, it floored me, to a blubbering wreck. Susanna, eleven, who lives in the Pembury estate next door said she’s seen me crying in the street, I tried to tell her sometimes when I’m happy I cry, she shook her head. No. You were sad, she said.

But it had disappeared, that feeling.

Like a friend departing. I missed that well of emotion. It probably meant I was healing over, from all that had happened in the last two years. But I felt like a husk, immune, so in a way I did wonder if the cycling might open me up again, get me to the place of sensitivity I sought. A couple of times my face cracked, walking under the moon for example, but I couldn’t tell if I was making it crack.

Down in Aix on my last night, sat in this very posh suite, the kind which looks nice and nothing works, I drank my complimentary half bottle of rosé and felt proud.

That something in me in my twenties, not even a healthy process, one that had made me want to cross continents on my bike as a form of self-flagellation, had now deposited me, calmer and more upright, in my late thirties, with a confidence to traverse a country, alone, up over hill and dale and mountain pass and meadow sweet, and breath in the experience, to restore me.

And I don’t often feel proud.

But still I couldn’t cry. Not in the way I hoped. And that made me sad. Because I hadn’t found what I was looking for. Like I’d found the gold, but not the Arkenstone.

POSTCRIPT

Ten days after returning from the continent, I am on the phone to my mother, she is driving. I tell her about what I saw at the weekend, half way up a hill in Somerset. How when everyone had gone to bed, I had stood there with my arms inside my shirt for warmth, shades on, just staring, for twenty minutes straight, at these people, the likes of whom I’d never seen. As if they had come up through the roots from the bowels of an otherworldly realm. They were fairies, woodland creatures, not from the earth.

Well darling, my mother said calmly, and my mother never really says this stuff, ever, maybe those people have been on that hill for a thousand years, maybe you were looking a thousand years into the past. I think about her words now and the hairs on my arm stand on end.

For the last two weeks, since that hill, since that weekend, I am open again. I feel involved in the world, in the smile, the glance, the sway of the leaf, the sunlight on my pillow, perhaps like never before. I feel a glow inside me, and what’s more I can share it, I feel people responding. Something came back with me from that ball of human energy and delight, some sprite, some puppeteer. Pulling its strings, dancing and laughing and pirouetting in the air. Everything makes me cry now.

And I am thankful.