The greatest cure I ever found for a drinking habit is for something godawful to happen. You can try any number of things, but a crisis is key. It could be someone dying, bankruptcy, watching your labrador get flattened by a Toyota Yaris, any of the stuff that makes people turn to the booze. That’s where you want to be. In my case it was a broken heart. But any kind of severe upheaval is on the money.

What will then happen is you turn to the booze with a reckless abandon. A couple of weeks of hard drinking is bang-on. The booze will drown out the voices, will numb you from your predicament. You’ll wake up a mess and mood-alter as soon as the chance presents itself, you’ll hunt down company, hit the pub with people you don’t even like. Distraction of any sort, so long as you don’t have to sit for a second in the pain of the present.

When your veins begin to pulse with alcohol, and your head is the kind of thick fog familiar to the characters of Bleak House, one morning after another night on the sauce your world will collapse. The adrenaline of your new situation will have run dry, and you will walk for three hours through a park in tears listening to old therapy sessions on an iPod trying to find any kernel of wisdom to save you from your pain, but the emotional depths will overwhelm you and you will discover a new type of despair. This is exactly where you need to be.

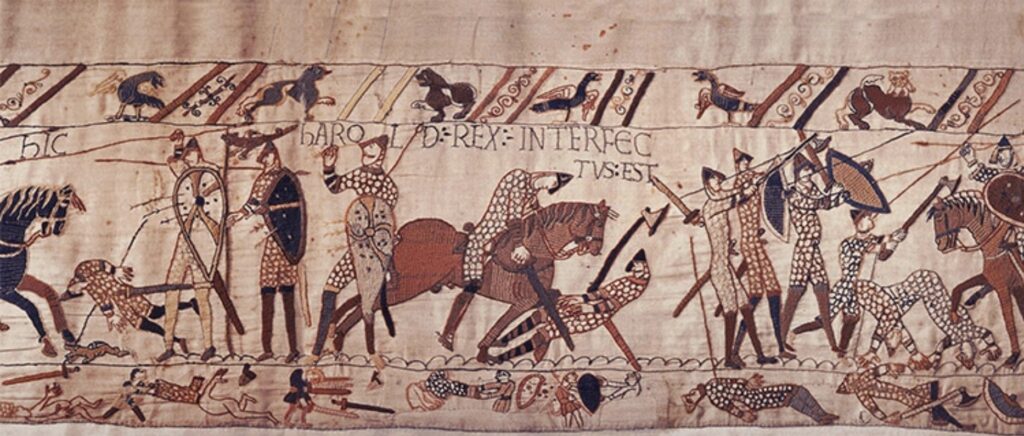

Rock-bottom.

The moment of clarity.

A place I found myself in the last week of September. Saturated in feelings I had processed none of, since all I could process was the alcohol I had saturated myself in. And the answer came: stop running. And I surrendered. It was extremely logical and obvious and remarkable in its simplicity. Enough. The booze wasn’t working.

*

I tried to stop drinking four years ago. An excess of excess had made me seek change, but after two months I’d jumped off the wagon to save myself from sobriety. The clarity that being sober revealed was terrifying. I had stared into the abyss and as Nietzsche warned the abyss had begun to stare back. With nothing to distract myself with or lose myself in, the mirror had shown me what I wasn’t ready for, and it had scared the life out of me.

But this was different. There was a voice in me now demanding I get my shit together. Not because it could be good for me, but because if I didn’t I was on the road to somewhere much darker. This time round I wasn’t so much stumbling towards an ideal, it was more like I was running from hell.

I just couldn’t repeat that walk through the park again, my head on the verge of eruption, at the edges of my sanity. I yearned for clarity. For clean clear lakes of Perrier, waterfalls of San Pellegrino, I wanted early nights and rooster crows, white towelling dressing gowns and Nescafé Gold Blend.

I wanted to sit in my feelings and let the pain hit me like a truck. Instead of running, I would go into the darkness to find what still shone. The move into sobriety was as uneventful as dew disappearing on a morning of spring. There was no ceremonial last drink, no sacrifice. Only a feeling of sanctuary.

Besides, it was only a girl.

I flew into non-alcoholic beer research. Turns out I had options. In the intervening four years since my last attempt, great leaps had been made and most pubs had at least one of these badboys on offer. Peculiarly thin at first, the more you drank the less you noticed the lack of kick. It was very placeboey. More than anything you could sit there with a pint full of some amber liquid and nod earnestly and feel like one of the fucking guys.

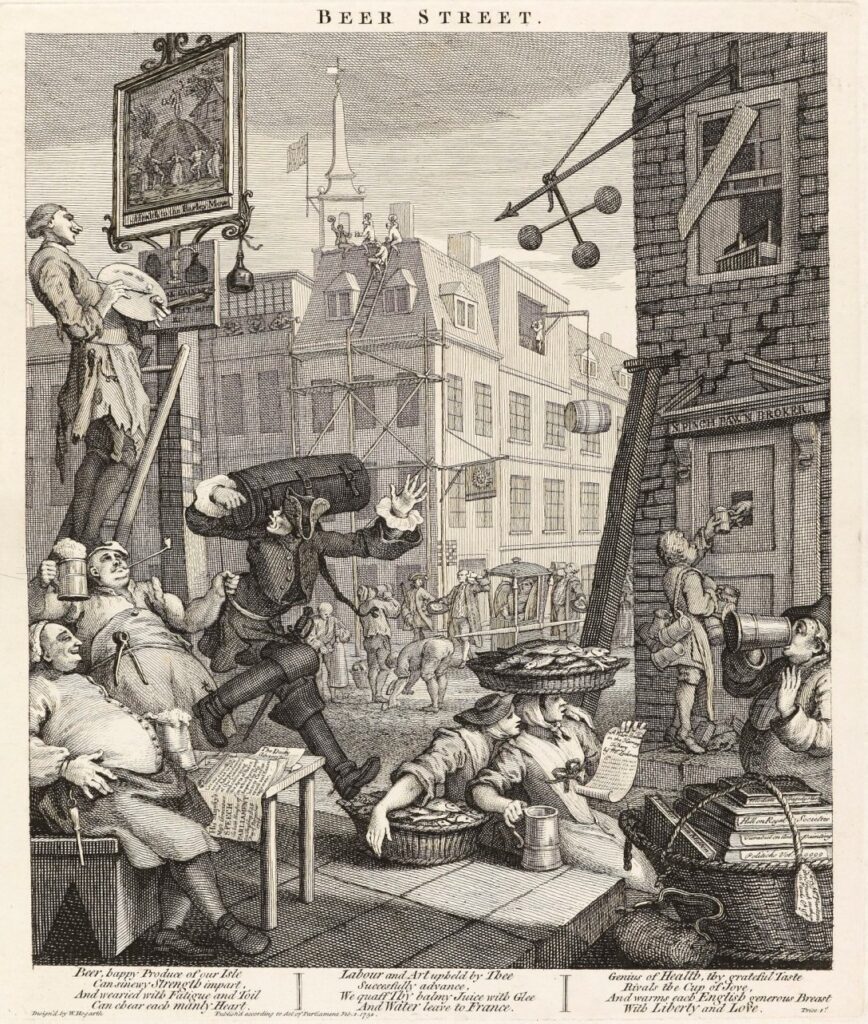

But when the call came for same again an interesting thing happened. Forcing another enormous container of liquid down me was just non-sensical. I wasn’t exactly thirsty. And yet the whole pub was doing it without a second thought. And I understood we love drinking not for the tannins and playful notes or the hops and the citrusy twang, we love drinking for what it does. Remove alcohol from the equation and you have nothing. You have Ribena. We drink for one reason.

To open a door into the unknown and walk through it.

I tried to unpick my drinking habit. First came the how. I was never an eight-pint man, or a half bottle of Malbec on a Monday night brother. I was a crafty at midday on a Saturday guy. A solo sharpener at the bar on a Thursday kinda cat. I lived for the ‘moment’, the first couple sips. The dance with the doorman of the unknown. I drank more than some and less than others. Pretty vanilla, with a dash of Cointreau.

The why was a different story. I remember recognising a period in my life when the role of alcohol changed. Like it began to mean something different. It went from exciting to calming, from a place of fun to a place of refuge. Not all the time, but still a shift. As if I was no longer excited by the fairground ride, I just wanted to be on it. A place I could sit in, that turned off the voice yabbering in my ear about all the ways my life was not as it should be.

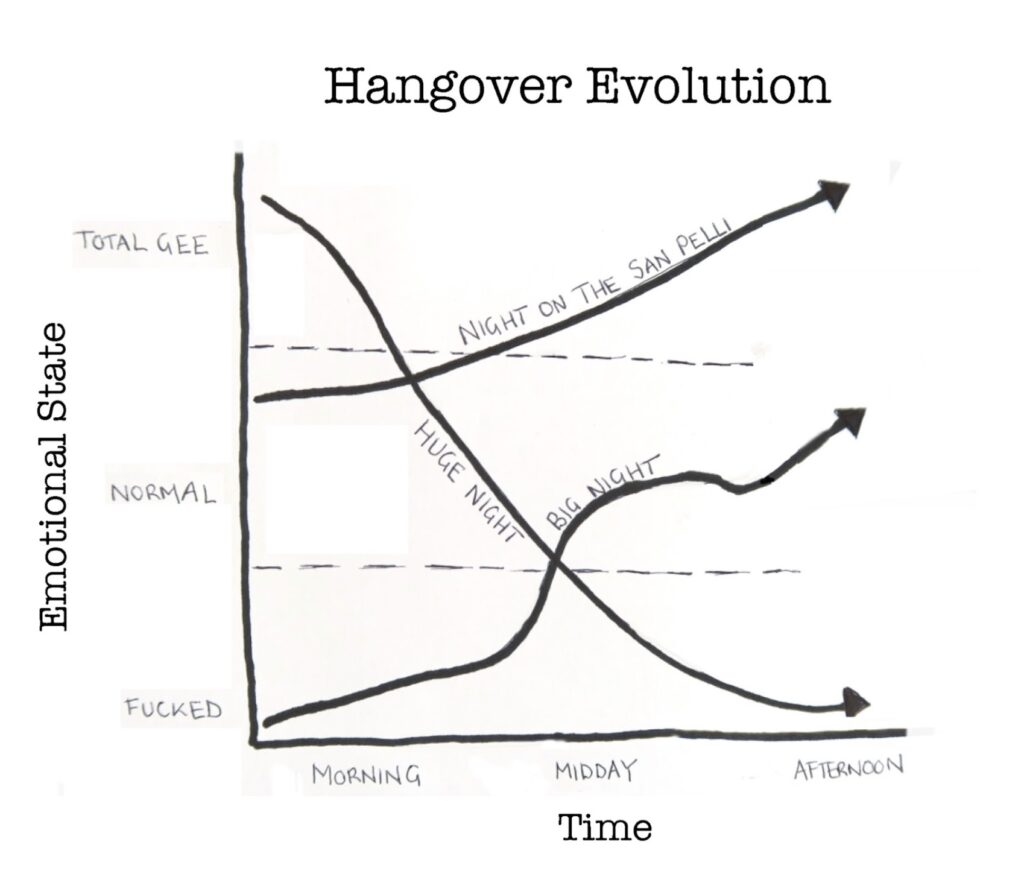

But it also meant I stayed on the ring-road of my problems. When things got overwhelming I’d hit the pub with a bro. And what awaited was distraction and hangover. Did I have a problem with drink. The hangover made me think I had a problem with me.

Hangovers for sensitive people are a first class ticket to Dante’s 7th circle. I’d come to where I’d left off two and a half days before, stripped of all confidence, picking my self-worth up off the floor. Hell was empty and my doorbell was ringing. My conception of myself evaporated. My friends didn’t like me. I couldn’t write for shit. I was no writer at all, I was a twat with a blog.

Imagine somebody gave you a pill and said swallow this and the pill made you feel exactly like a bad hangover. Nothing in the world would be worth this feeling, you’d think. The blanket negativity, the nausea, the delusion and insecurity. And yet we double-drop that pill most weekends, because all we see is the effect and not the cause, all we feel is the edge that needs taking off.

That’s what walking through the park was, fifteen of those pills at once. A beer-addled brain walloped by the news that the person I loved most in the world needed space from me. But that morning in the park saved me. Without it, I wouldn’t be where I am now.

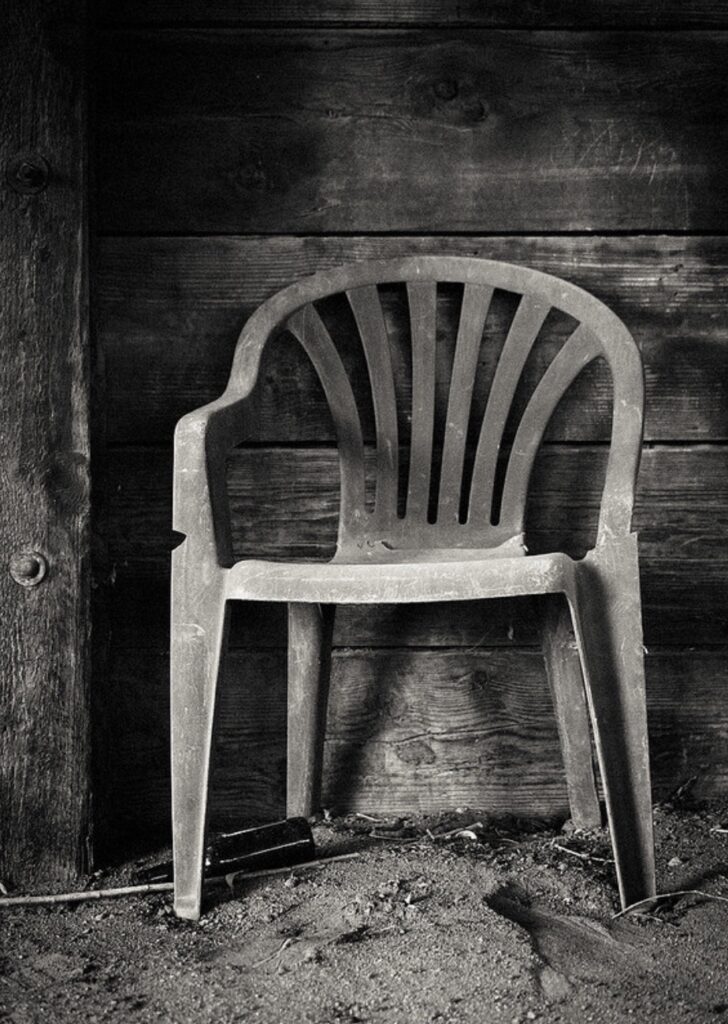

Domingo T-800. Cybernetic organism.

Living tissue over a metal endoskeleton.

I’ve done more DIY in the last two months than the rest of my life put together, I walk into Leyland and everybody knows my name. I’m a drill-bit away from building an orphanage in the jungles of Nicaragua. I repainted bedrooms, cleared out cupboards I’d forgotten existed, took down a couple of 1000 piece jigsaws. I lost 6 kilos. Which considering I switched vices and started smashing a family pack of peanut m&ms most nights, is impressive.

More than anything the clarity brought momentum. I’d bed down at half nine and rise before dawn and there was no drop-off. Only incremental steps and a feeling of same-same or better than yesterday. I was a better human, a better friend, brother, son, bit of cheeky banter for everyone. I think there was just no regret, which meant no mean self-talk, maybe I even liked myself a little. Above all no energy spent clawing my way back up to the surface, every morning began above water and from there I flew.

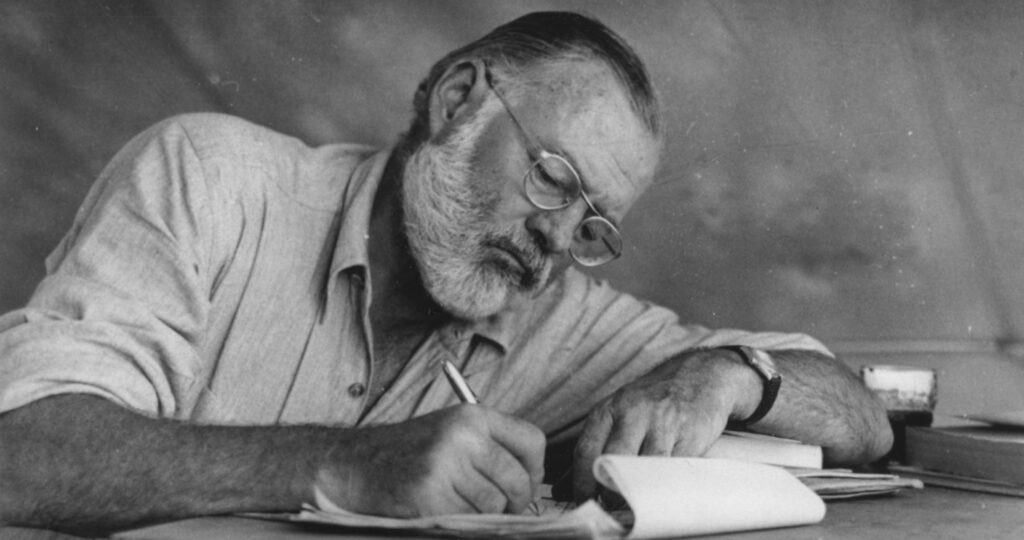

Hemingway drank to make other people more interesting. But watching people get all slurry and affectionate is a beautiful thing. There is a smugness in the containment, in spending two hours in a pub and cycling home knowing you can smash a whole page of Sudoku. I had my wild nights in. When you absolutely positively feel the urge to drink yourself into oblivion and show up for your niece’s third birthday the following day.

Accept no substitutes.

PINE TRAIL PALE ALE 0.5%

*

Sadly nothing is as good as it seems.

Every form of addiction is bad, no matter whether the narcotic be alchohol, morphine or idealism.

Jung

As the weeks have rolled on I’ve grown wary of this addiction to clarity. The more I avoid the hangover, the bigger its spectre becomes, the less I want to go near it. But I don’t want to live like that, always in control. How boring never to toast a pint in the sunshine, or swill an Umbrian red on your tongue on a pine-covered hill.

I don’t know if this whole thing is even about alcohol. I’d reached a point in my life where I couldn’t keep running from myself, I’d received a thump to the heart, and not drinking was my ticket out of there. And it has grown roots in me, I feel like a tree that cannot be bent by the wind. Jung said too the most intense conflicts, once overcome, leave a security and a calm that cannot be easily disturbed. But without conflict there can be no change.

So I guess life grabbed me by the balls and shook change out of me. That’s what happened. It was so necessary it was actually the easiest thing in the world. I couldn’t pretend it wasn’t happening or claim I wasn’t ready. It was time.

Going off the booze was symbolic of something bigger. Like I was finally looking out for myself. Not just me now. But me tomorrow, me next week, me in a year’s time. Earlier this week I took her photos down. I was dreading it but strangely enough it brought peace. To die to something, so in its place something can grow again anew.

And what ever happened to gratitude. For the quantum miracles that have occurred over billions of years to even get me here, with oxygen, with memories, with side one of Billy Joel River of Dreams, about to eat some tacos.

So that’s me.

Heart a little tattered but the best I’ve been in decades. Sadness might come and tap me on the shoulder now and then, and I have the strength to welcome it in and sit with it a while. Resolute and sound. How strange one of the worst things I can remember happening saved me. That in the darkness some things begin to shine with a light from another source. But we have to go where we least want to, down into the depths, and find an ember there on which to blow to cause the spark to light up once again inside us.

Some time in the new year, once the first buds of spring have tiptoed outside, I will cycle to a pub and stand at the bar with a mate and order a pint. A real one. With pleasure and no regret.

But I have some things I need to do. And now the booze, like another thing in my life, will have to wait. Gladiator’s mate at the end of Gladiator says it best. As he buries the little statues of his family in the sands of the Colloseum, he looks to the sky and speaks to his friend.

Now we are free. I will see you again.

But not yet.

Not yet.