Ahhh…

Christmas.

The season of goodwill, family discord, organised fun, 12 days of merde. Anyone who says they love Christmas is either living a lie or six years old. Against my will, having just been through a month of early onset SAD, I flew across the ocean in late December to a summer on the Argentine pampa, to appease my mother, whose priorities in life can now be broken down to two in number.

Uninterrupted siestas and family harmony.

I arrived. Having not yet unpacked, within 36 hours I was almost on a plane back.

On our first lunch, it quickly became clear my father’s anti-exploding-with-irrational-rage-about-literally-nothing medication had gone awol.

Such was the tension, such was the steam billowing out of both his ears, my mother had to grip the table with both hands to stop herself from leaving, my cousin did the finest act of international diplomacy I’ve ever seen, and all the while I sat there in shellshock, my right leg still numb from a 28 hour transatlantic KLM shitshow.

I’d been there for ninety minutes.

Things got worse before they got better.

My first few days were permeated by sleeping in til 11.30 and long walks in the pampa. The closed-door, it became known as, the door of my bedroom shut to the bustle of the house through mid-morning, became my parents’ affectionate codeword for ‘our son is having a moment’. I’d eventually make it downstairs, dopey-eyed and coffee-lorn, mumble for an hour about how I just wanted some privacy.

Harry Enfield stuff.

It wasn’t all struggle.

There was laughter and extended hugs, walks under the canopy of the huge trees. The sounds of the cotorra beneath the cedar and the swift chasing the chimango, the rustling of the eucalyptus. There were songs at table and poetry recitals, repetitive jokes, grave meteorological predictions about encroaching clouds, dinner by candlelight, stargazing.

At the beginning of Ana Karenina, Tolstoy writes:

All happy families are alike.

All unhappy families are unique in their own way.

He was implying I think that happy families are a fib. They don’t exist. What you get are short stretches of harmony. The unluckiest might not ever get there, the luckiest have it for the least brief of stretches.

How are families not going to fight each other, resent each other. The return to the nest, years after the flight from it, is a get-to-know-you all over again. Your folks aren’t used to it, you’re not used to it. My brother, with Victoria and Mary, me nursing a hangover from an unkind November, this melting pot and all the ingredients that went into it, every day was bound to bubble over.

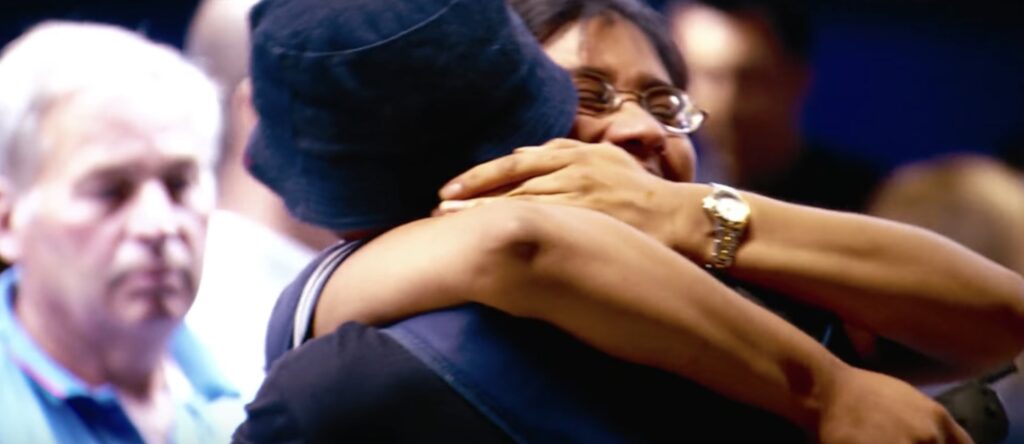

On the afternoon of Boxing Day, after some more hi-jinx, sat on the terrace with my mother, papa off in the pampa counting cows, I lost it, started heaving, my face wet with tears. Darling you can go if you must, I understand, she said. I know how hard your father is to be around sometimes. You do what you need to.

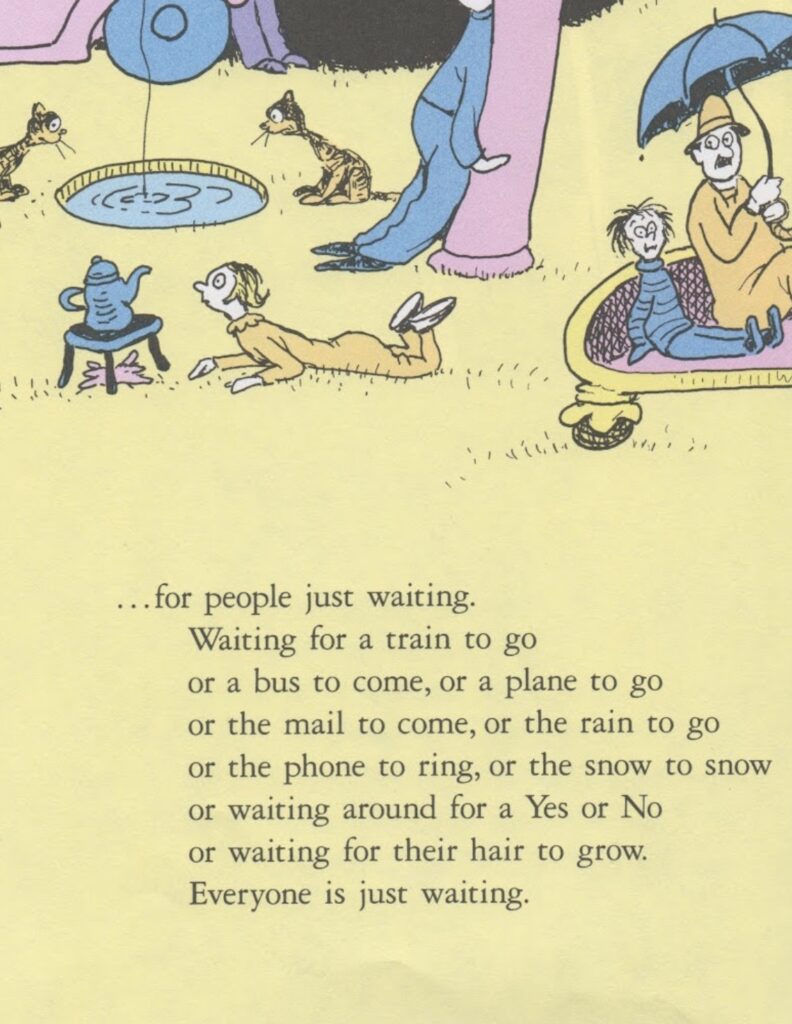

There I was, six months away from 40, blubbing to my mum about how my holiday had become a holiday from hell, and yet, as unjust as all this felt, it was familiar. Isn’t that the problem with Christmas with los padres.

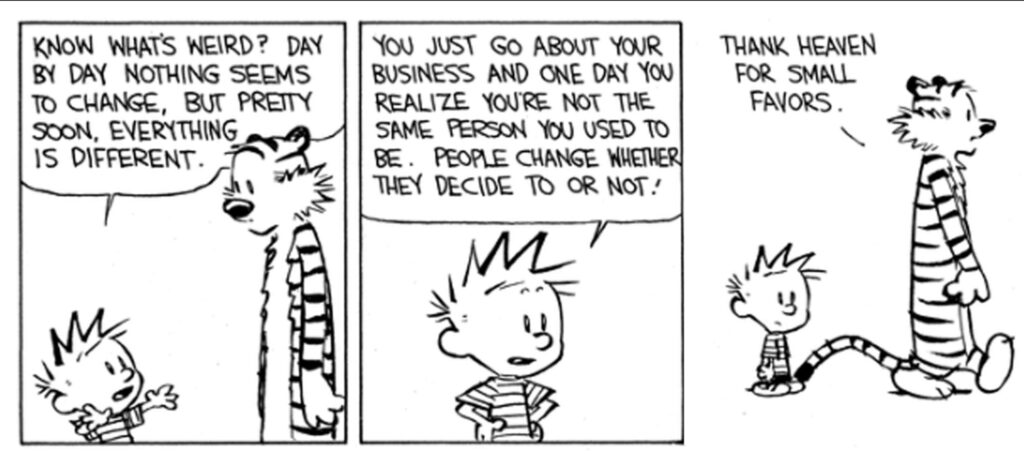

It’s time-travel.

You ain’t 39 son. You’re six. Enter the hissy fits, the screwfaces, the stomping out, the long walks. It’s totally infantilising. Around them you ride a DeLorean straight back to childhood. You’re standing there in front of the people that made you. You can do your best I’m a man of the world impression but the same shit that took you down when you had no front teeth to speak of is just as hard to swallow.

*

I remember in a restaurant in Knightbridge once with my mother, I must’ve been 26, I said pointing to her stomach, Mummy, do you think the fact that I came from in there, and that you made me in there, does that mean in some weird way you’ll have a connection, a strange sort of agency over me for the rest of your life that no force can break. Smiling knowingly as if I’d said something quite dumb she said, yes darling.

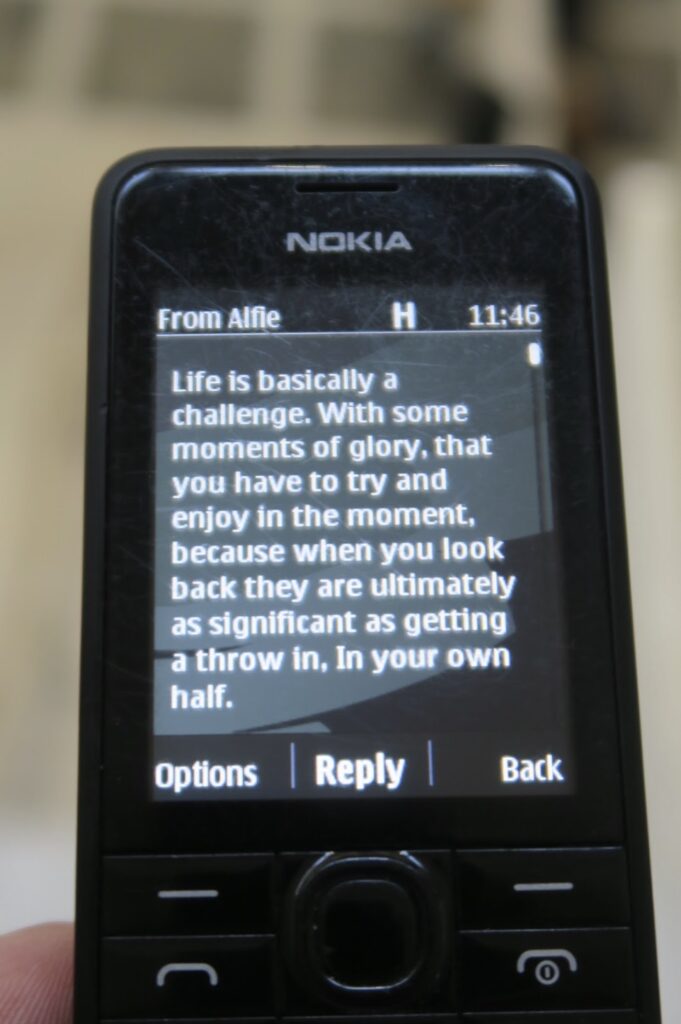

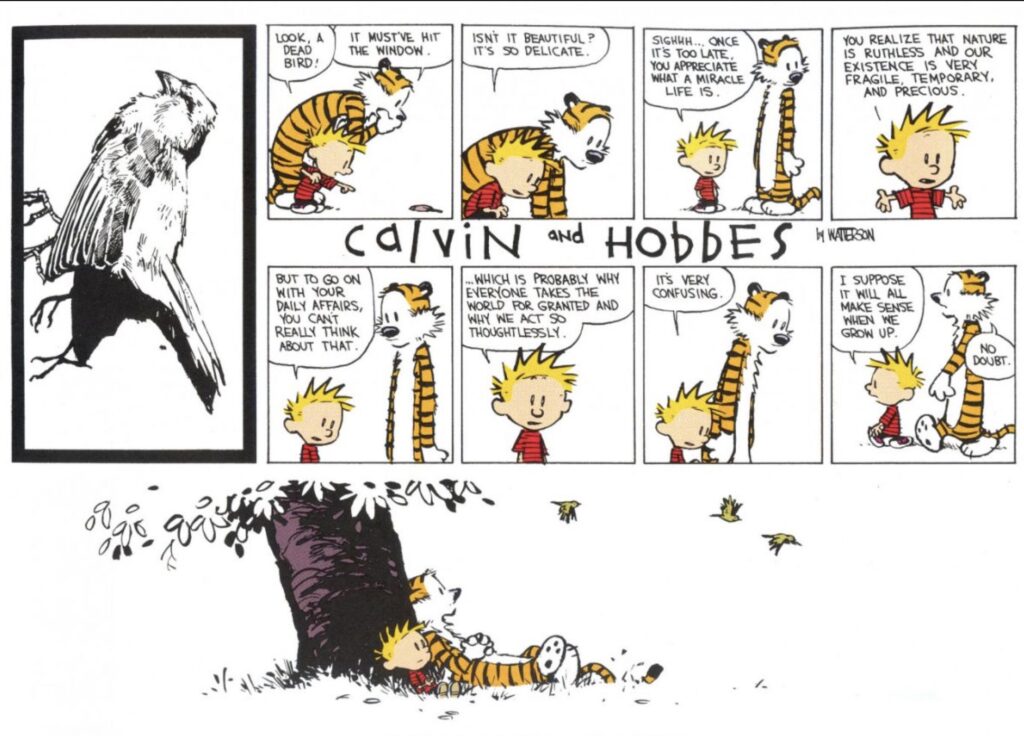

Now comes the period of our lives when our parents stop hanging about. It’s maths. Some have been gone for time now, some have started to leave only recently, many friends are now in the process of deep grief. Wondering where they are, how they can have left, just like that. It is a reminder for us lucky ones to double down. Life is short, it brings that much home, wrote a friend in an email yesterday. Her mother had died only the day before.

*

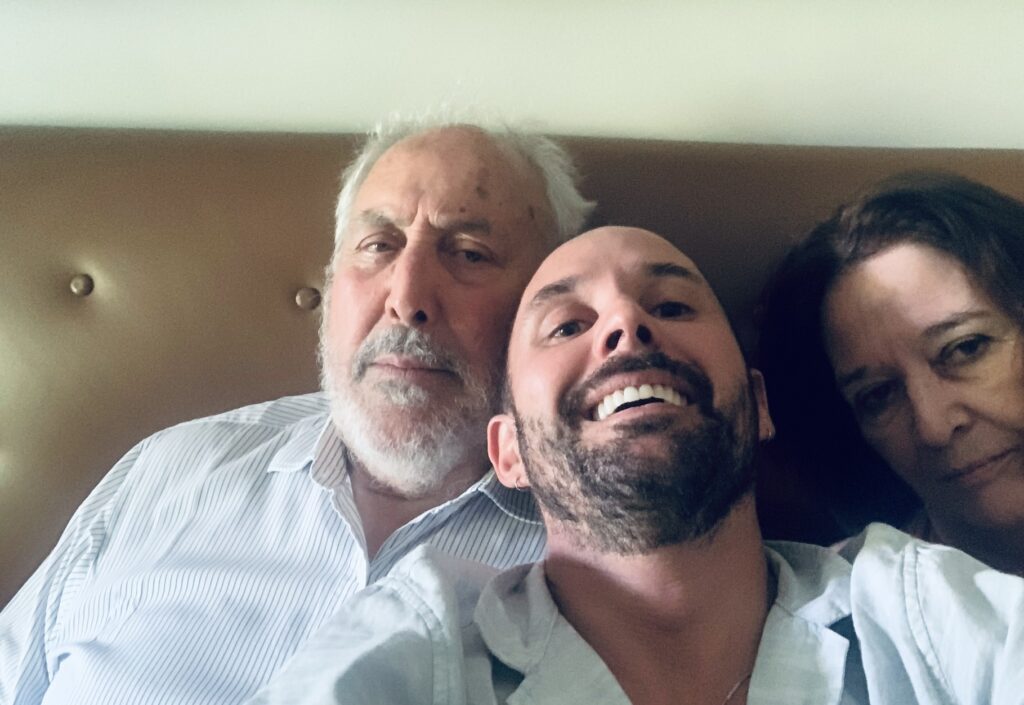

Back in the pampa, day became night became day, downstream we drifted towards the New Year. The fighting thinned out, the makeups became more productive. A rhythm was found. The New Year was welcomed in in the courtyard with dancing and speeches, all the Estancia sat round the table.

My brother and his fam flew back, leaving the three of us. Sidling into each new morning, days swaying into one another in the manner of the branches above our heads, we’d sit on the terrace in the evening discussing the hide and seek of the moon. I began to get out of bed at a normal hour.

We’d breakfast lunch and sup together. I hadn’t spent this much time with my parents since I was fifteen. Everyone had their topics. My father’s was his happiness, his wholeness, in his homeland, surrounded by his earth. Mine was spirit, synchronicity, woo-woo stuff. Guys, do you think that fly just landed on me for a reason. My mother’s topic, more important than any of ours, was being allowed to speak now and then. Two latin loudmouths interjecting and projecting.

But it was lovely.

That first week of January was something special. I wouldn’t have got there if I’d bounced, abused my superpower of finding the first available exit when things get heated. Like that line from American History X, if you leave now you will find no peace.

Life teaches you how to live it if you only give it time.

I’d get friend updates from Blighty now and then, each one in the middle of their own familial shitshow. ‘Bloody boring’, ‘traumatic’, ‘how long can this go on’. Maybe, I thought, I have it better than most. We might scream our heads off at each other, but there is a lot of connection. Lots of deep and meaningfuls, in-jokes, listening, taking turns to speak, walks under the moon, the odd bout of feet-tickling.

By the end, my heart was heavy.

Predictably on our Last Supper, one of my parents said something that threw me into such a prepubescent rage that I became catatonic for half an hour. Didn’t say a word. Eventually wandered off into the night, on one of my ‘walks’.

Parents.

Can’t live with them, going to have to work out how to live without them. Looking out across the laguna nursing a beer with my cousin Francisco, he said, you don’t know how much I’d give for an hour with papa again. Just an hour. So don’t take him for granted. Me acompaña, he said. He’s there, when I wonder what to do, I ask myself what would papa do. He talks to me.

This Christmas showed me the beauty and the horror. All things in opposition. Taught me to not take for granted the people that made me, that might have more to teach me than my stubborn mind might be willing to concede.

When Larkin said they fuck you up, he really was stating the obvious. I’ll see you and raise you, Phil. They give you the gift of life. And no life, however completely miserable, is pointless. Frankl went through the camps. Still, he said this:

Imagine you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favourite symphony, and your favourite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine, and now imagine it would be possible for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like ‘it would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!’

Sat there alone the other night watching Arrival, my face cracked. Much more than a film about alien visitation, it was about the choice to spend time with the people we love, knowing it won’t and can’t last forever. The Heptapods, and their ability to see time non-linearly, had given the main character a vision of her future, in which she would have a child who she would then go on to lose to a rare disease.

If you could see your whole life from start to finish, she asks at the end, would you change things.

Einstein believed the same, that past present and future were happening simultaneously. Another thing he said, is there are two ways to live. As if nothing is a miracle. And as if everything is. There was a thing to think about. Why is there even anything at all. And still there is. We should be grateful for every day of our lives. Every hour. Every minute. Even a nanosecond of oxygen is subscribing to the miracle of everything.

To mummy and pops, reading this. (as they always do.)

Holaaaa.

Les extraño.

Tell them you love em, and you miss em. Even if they’re up in the sky. They’ll be listening, I think so. Hear what they have to say. If you can’t make it out, listen harder. They will whisper in your ear.