I had been pounding my mountain bike through dense forest for over an hour.

The sinuous track finally straightened and I crested the pine-coated hill. I looked over at Wilma and grimaced, then stared out across the vast unending lands stretching out ahead of us and channeled the last of the Mahican in me. These were the territories of the Native American tribes who had roamed freely over these hills and prairies for tens of thousands of years, existing in a deep spiritual communion with a sacred earth they called a mothering power.

I was born in Nature’s wide domain! The trees were all that sheltered my infant limbs, the blue heavens all that covered me. I am one of Nature’s children. She shall be my glory: her features, her robes, and the wreath of her brow, the seasons, her stately oaks, and the evergreen.

George Copway Kahgegagahbowh, The Ojibwe People (1848)

*

That was in 2016, near the beginning of a 2,800 mile bike race that ran the length of the Rocky mountains from Alberta in Canada to the US border with Mexico. That trip was about as far from normal as a bike trip can get, but is an example of the fact that for the last decade of my life, it’s become clear that I can’t really do any travelling anywhere if I don’t have my bicycle with me. I wouldn’t really know how.

In 2007 when i was 24, my mate Guy and I took some bikes to Japan on a journey into the unknown, and thenceforth spent the next few years chasing the two-wheeled dragon wherever we could. We braved the southern spaces of the Arctic circle and unending daylight in Norway, and traversed Eastern Europe from Poland through Slovenia, Hungary and the Ukraine, crossing the Carpathian mountains into Bucharest.

In 2012 I took up the reigns alone, and went to the Andes for six weeks. That was the first trip that really scared me. 43 days at 3,500 metres above sea level, nights so cold water would freeze inside my tent, migraine-inducing altitude, you can read an account of it here. Closer to home my bike took me through Italy, the Alps of Austria and Switzerland, it showed me the length of Germany, there were forays through Holland and Belgium, and France many times over. And a month exploring New Zealand.

I’ve been eaten alive by sand-flies in a river near Dunedin, suffered third degree sunburn in the shadow of Mount Cook, had 3am hallucinations in the deserts of New Mexico, slept in a village on Japan’s east coast that has since been destroyed by a wave, was run off a mountain road by the Romanian mafia, and bought apricots off a 60yr old Ukranian woman with a handlebar moustache. I’ve looked down roads I can’t see the end of, camped out in the middle of them, got more lost than you can ever fathom, I’ve felt the most sad, tired, confused, and by turns the most at peace, elated, and alive I’ve ever felt in my life.

All from the saddle of a touring bike.

*

Discovering the world by bicycle has become my favourite thing in life. It is something I crave when I feel distant from it. It is something I feel a physical pull towards. And is something that fuels me for months once I have returned from it. Until the point where that flame has weakened and splutters and I look for the next chance to go again.

I thought long and hard as to why I felt this so strongly, and I came to a realisation. This physical pull, this joy, this peace of mind, this aliveness, this residual contentment in its aftermath, none of it is actually about the bicycle. Not really. It’s about where the bicycle deposits you. I realised that it was about something far bigger than just the bike. It was about getting the hell away from cities, and getting back into nature. It was something wise and ancient inside me, calling me back to the mountains and the rivers and the birdsong and the silence.

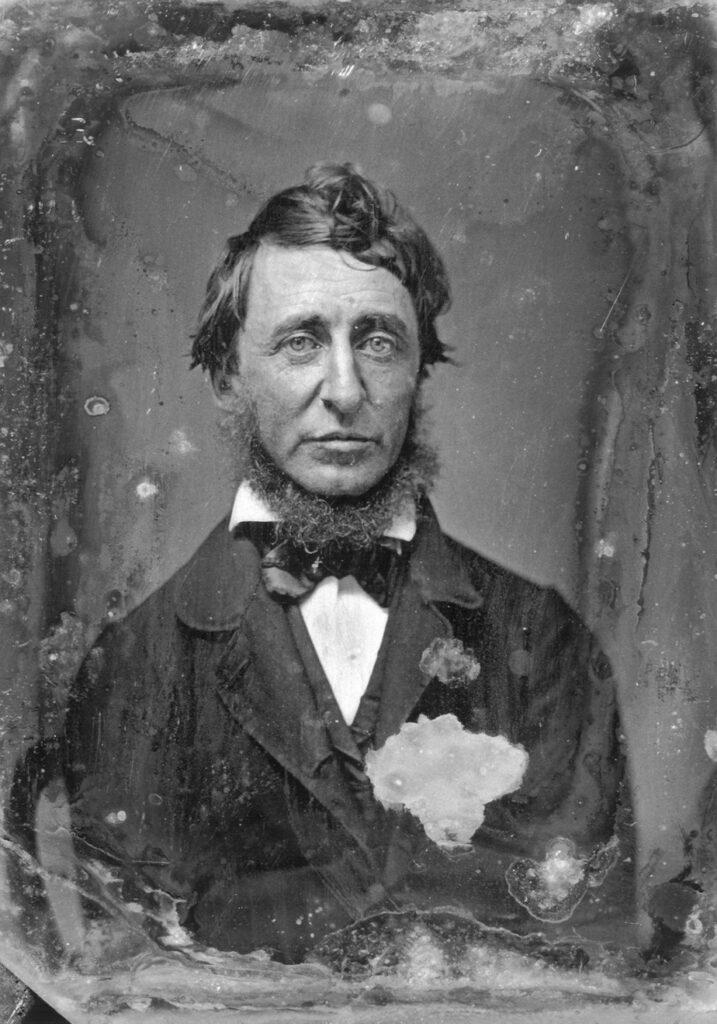

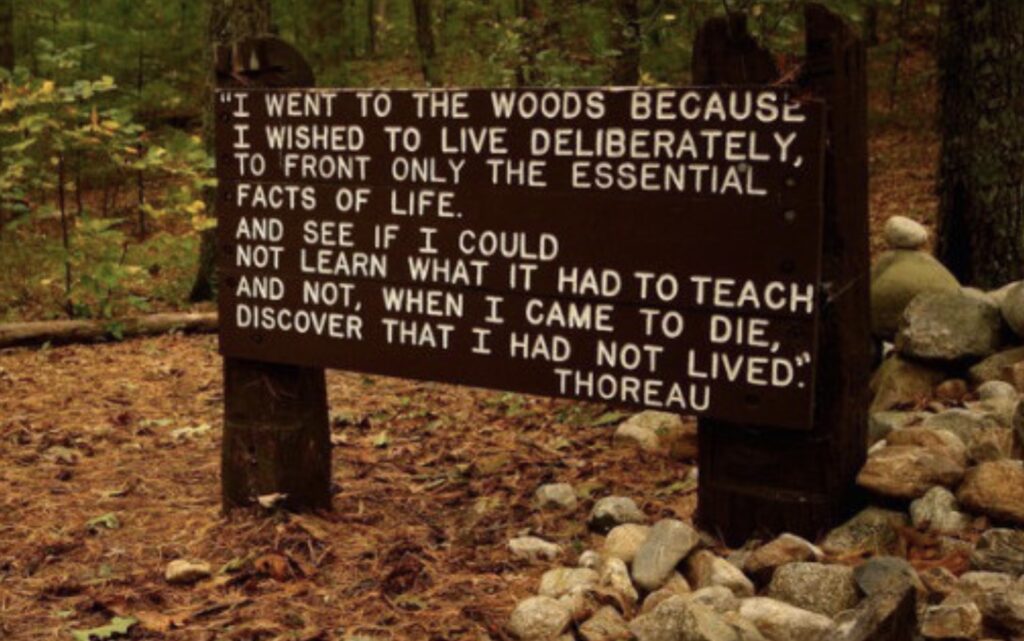

In 1845 the American writer Henry David Thoreau, in his late 20s, built himself a small cabin among the pine trees on the shores of Walden Pond in Massachusetts, wanting to see what it would be like to live cut off from other people, in communion with nature. He summed up his experiences in the book Walden.

He went for long walks, read, mended his clothes, gathered fruit, went fishing and mused on what holds us all back from living in this way. Amid the trees with only birds and badgers for company, he ate and lived simply, but felt like a king. At the end of his time in the woods, Thoreau returned to the modern city sceptical of its so-called achievements and determined to live according to the wisdom and modesty that is the gift of the natural world.

Thoreau was tapping into something innate. This need to be in nature, I have come to believe is deeply nested in every single one of us, thanks to the seven million years of human evolution, and the hundreds of millions of years before that, when we lived in the world and all of the world was just trees. What Thoreau was saying was the same wisdom the Native American tribes had passed down between them since time immemorial.

Nature’s features, her robes, the wreath of her brow, shall be our glory.

I remember one morning lying against the trunk of a giant Eucalyptus in the South Island of New Zealand, looking up and watching its branches and leaves silhouetted against the sky dance in an almighty summer wind. And an intuition came to me that I’ve never forgotten. Straight out of left field. Nothing is wiser or cleverer than nature. I remember thinking it clearly and indelibly. Nothing has been here longer or is more perfectly designed or knows more. It was here before us and will be here after us, and we should pay attention to what it has to say.

Getting into one environment can also get you out of another. And the world of screens and status updates and vibrating alerts and inadequacy, the world of rush hour commutes and screw faces and carbon monoxide and fear,I think we could all use getting the hell away from for a minute or more. It’s not just what nature can give you, but also what it can take you away from.

I wanted to write this because I’m off on my bicycle tomorrow evening at dusk, my ferry lands in Saint–Malo on the north coast of Brittany at eight in the morning, and for the next ten daysI will trace a path as far down the belly of France as I can get. I have my tent, some reading material, a notebook, some clothes to mend, some fruit to gather, the company of birds and badgers, and some fishing to do.

I was going to make this a detailed account of the tiny things that make cycle touring so majestic, but I thought i’d use the next two weeks for research. So here’s Wild Geese by the poet Mary Oliver, if you want you can find her propping up the bar with Thoreau and Kahgegagahbowh, the fellow with the feather peaking out above his head at the start.

They’re all singing from the same hymn sheet.

Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and i will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.