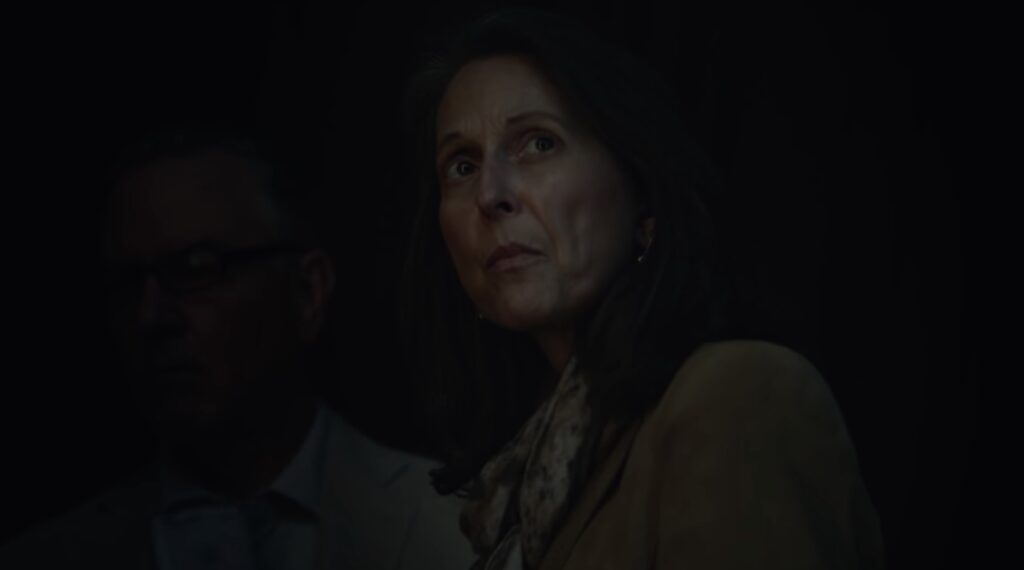

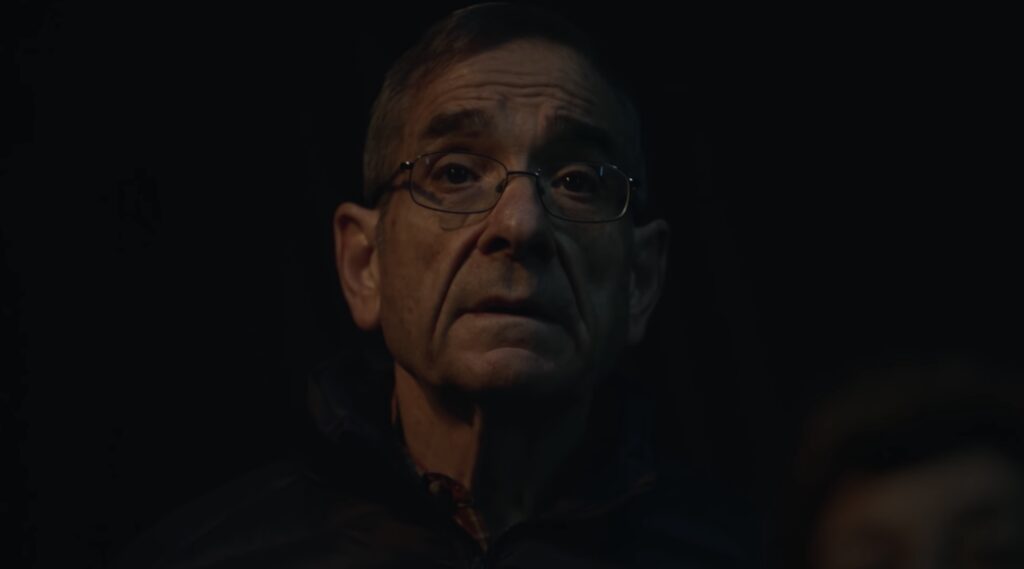

So there I was the other night, deep in a YouTube hole, feeling its algorithms clank and churn and some video loaded and began to play and it changed the course of my evening. It seemed pretty inauspicious, just a bunch of people taking turns to look at a painting. But as I watched something strange happened.

Fifteen seconds in the hairs on my arm began to stand on end, a minute later my eyes were wet with tears, and by the end my face had cracked into some sort of cubist jumble. With salty cheeks I gathered myself and wondered what the hell was going on.

The eyes of these people were trained on the Salvator Mundi, a painting of seismic historical importance once thought lost, but after cleaning and restoration, newly attributed to Leonardo de Vinci.

The hype was real.

It was sold at auction by Christie’s New York, and for two weeks prior people queued in the rain the length of entire blocks to catch a glimpse of it. The painting the size of a lunch tray went for £450m, the most expensive artwork ever sold. Then disappeared.

I watched the video a few more times to try and recapture the emotion I’d felt, which came easily, and resolved to get to the bottom of this thing. What had I reacted to, what was it. Awe in the face of supreme beauty? Why would that move me to tears. Why do we have a strange physiological reaction to beauty.

Where does awe come from. What purpose does it serve.

*

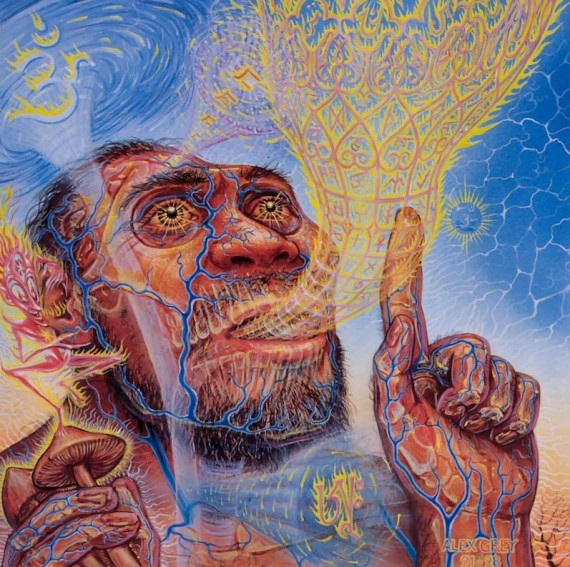

Eight million years ago a group of chimpanzees making their way through the African savanna stooped to pick up a mushroom. They found more and ate a bunch and again strange things started to happen.

The stoned ape theory claims that chimps experimenting with different food groups led them to psychedelic psilocybin mushrooms, which upon ingestion began to radically alter their behaviour. Over millions of years the mushroom trips led to heightened vision, the invention of language, harnessing of fire, and some argue the inexplicable doubling of the human brain size.

Scientists don’t really buy the stoned ape theory. But an early hominid getting high is still meaningful, in that it must’ve been the first instance of the elevation of the animal brain into the realms of the transcendent. The first time a living thing might’ve been aware of something far bigger than itself, and felt awe.

Scientists now think psychedelics were behind all prehistoric cave art. Without doubt the psychedelic experience has been responsible for the birth of religions and profound leaps in cultural evolution.

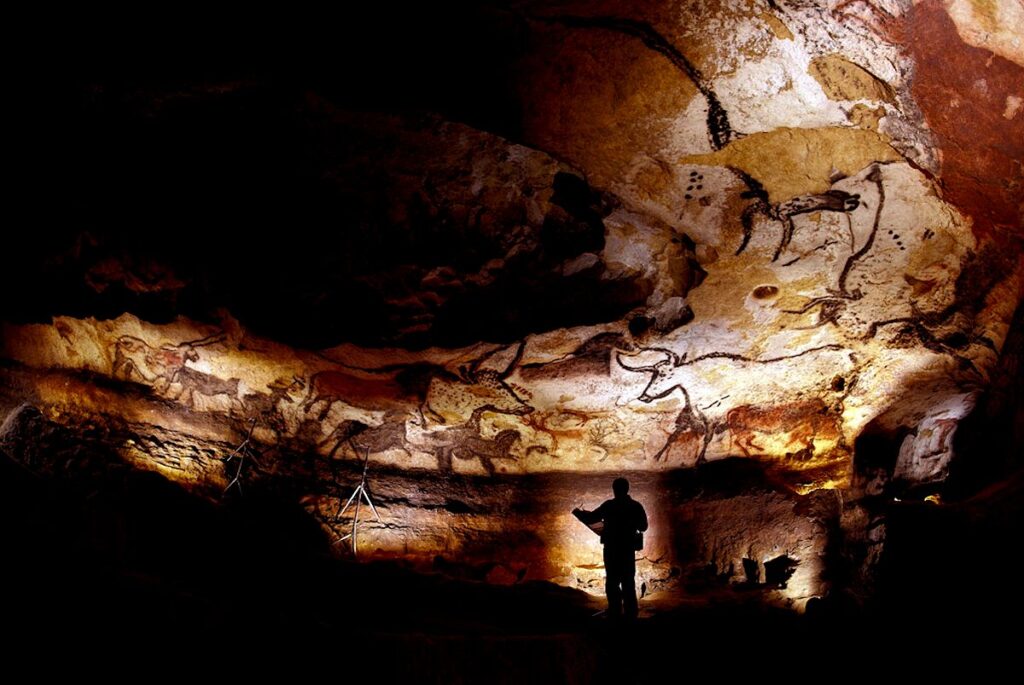

When Picasso clambered out of Lascaux cave in 1949 after seeing the bulls and lions and rhinoceros that had lain undiscovered in their darkness for 17,000 years, he exclaimed in wonder at his ancestors… we have invented nothing.

But what do psychedelics have to do with looking in awe at a Leonardo.

Turns out the neurochemistry in the brain is identical. When the brain experiences awe, the default mode network, the part responsible for policing the interaction of multiple brain regions, dims down, and as if let off a leash the brain begins to make connections it would otherwise be totally fenced off from.

The brain switches its focus to the right hemisphere, the part responsible for imagination and intuition, and what results is a feeling of deep connection to the world. Awe has been called ‘the perception that is bigger than us’. On psychedelics, the same part of the brain is activated.

Early humans eating a bunch of mushrooms and staring at the heavens would’ve encountered mystical experiences completely outside their daily remit of hunting and gathering and finding shelter. Inspiring them to create representations of what they saw on the walls of caves.

But why.

Why do we have a capacity for awe and mystical experience.

Why did watching a bunch of people in New York be so affected by a painting make all the hairs on my neck stand on end, piloerection, the same thing that happens to a cat when it sees a particularly big dog, and reduce me to a blubbering wreck. How did it improve my life.

Victor Frankl, the neurologist who wrote Man’s Search For Meaning about his time in the concentration camps, thought awe was about meaning. Beyond personal responsibility, he thought we could face up to the demands of existence through a loving dedication to beauty.

‘Imagine you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favourite symphony, and your favourite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine, and now imagine it would be possible for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like ‘it would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

*

The splashes of beauty around us, thought Frankl, were there to pit against the one constant in life the Buddha spoke of, the fact of our suffering. That what touches us deeply might lift us out of our drudgery for a brief moment to remind us that all is not so hopelessly lost, if only we look hard enough.

Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on cottonwoods

Leaves floating on trout streams

And above the hills

The high blue windless skies

The unexpected smile from the bus driver. The floated echo of the empty church. The smell of the air after new rain, the lick of condensation on the pint glass, the Jack Wilshere goal against Norwich someone uploaded to Pornhub.

*

Maybe the question is not why we have the capacity for awe, but why we walk around so blind to beauty. There are those who see too much beauty, who grapple all their lives with it. They look and look and look and report back on what they have seen.

Artists remind us that everything however small or insignificant is worthy of infinite attention. Their lesson is this. All that there is, can be found exactly where you are, always. We are everything, and everything is us, and so the finite becomes infinite. The psychedelic lesson is the same.

What Blake meant when he wrote:

To see the World in a Grain of Sand

And Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Being in a permanent awe-addled state might be slightly inconvenient, given that we would forget to eat and probably starve. So the brain has a prefrontal cortex. The linear, logical, problem-solving part of the brain, the 18 stone bouncer manning the doors of perception, hellbent on sleep and food and survival.

Working overtime while the larger parts of our brain remain mostly dormant. Freezing out the default mode network from making its connections. Fencing us off from the sublime because we could not reside there. Perhaps in the end, awe is the transcendent slipping through the cracks.

‘It was an April day’ wrote Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist who discovered LSD by chance and dedicated his life to the study of it, ‘and going out into the garden I saw it had been raining during the night. I had the feeling that I saw the earth and the beauty of nature as it had been when it was created, at the first day of creation. What an experience! I was reborn, seeing nature in quite a new light.

Go to the meadows, go to the garden, go to the woods. Open your eyes!’

*

Eight million years ago a hungry chimp ate a mushroom and pulled back the veil and got the party started, and here we are. Strange living things carrying inside us a bizarre capacity for mystical experience. Nature, psychedelic plants, meditation, outstanding works of art and literature and music, love, from inside them the unknown shines out, sparking an ember inside us.

Pushing us out to meet something bigger than ourselves. A sense of connection to the universe that is normally far beyond the narrow band of our consciousness. But is there all around us, always, if we keep our eyes open wide and learn how to look.

A portal to the divine.

Or perhaps the Divine reaching down to brush us with the tip of a finger.