The darling buds of May dangle forlornly with ice. For three days my socks are soaked through, my feet ache from the cold and I move eastwards through falling snow into a headwind, cursing my idea that France meant Mediterranean sun. On a nasty winding climb my gears lock up and I scream out in rage. My only company are the creaking pines and my rage is a fart in the wind. A well of happiness that has lain empty for months is filling up inside me. Whatever befalls me now won’t make a shot of difference, I think I have been saved.

*

A few hours into the first day of January of 2019, someone posted this.

My year has felt a little like that. Imagine sleeping through a whole weekend, going out alone on a Monday and getting totalled, waking up and feeling like shit all of Tuesday, with nobody to text about what a strange impromptu night it was. 2019 has felt like that kind of hangover, close to every day. When it threatened to get good, I would wake up on that same Tuesday all over again. Lapping against my shores was a lake of unease, joy was a stone skimming across its surface.

Ratcheting up the pressure and relieving it at will, a mild depression had had me by the balls since November. Too mild to knock me out, but still the mental health equivalent of a small annoying dog humping my lower leg. Every day I watched the warfare of a city fighting harder than I was to stay alive, the siren wailing and check-out lines and sad eyes staring from the top of night buses, folk surrounded from all sides but achingly alone. Joy was there somewhere around the next corner, and I was moving down the wrong side of the wrong street.

*

The Bordeaux airport Ibis Budget hotel is a strange environment to find a new lease of life.

In the past, when things got top-heavy I’d often look to the bike for an out. To go away into a new environment, to raise your heart-rate, to breathe clean air and be enveloped by green, the experience is rich because it is all new. Cycling across a country albeit with maps, is raw unmapped territory for your mind, it is taking five big gulps from an ice cold pint of adventure. We all need some adventure in our lives once in a while.

And so I found myself in the Ibis Budget Airport hotel just west of Bordeaux with my touring bike propped against the wall, lying starfished in the dark as the hum of jet engines sang me to sleep, feeling an emotion I hadn’t been able to muster all year. The kind of excitement only a free man can feel, a man at the start of a long journey, whose conclusion is uncertain. Lyon was my destination, 700km directly eastwards across the rolling terrain of the under belly of France, with a date to keep six days from then on the steps of Marylebone Town Hall, to watch my brother getting married.

This mood of mine had lingered inside me since early November, at times subsiding but never leaving altogether. It occurred to me that sensitive people have these pores that are open all the time to emotional information, good and bad. When depression rears its head it makes the information coming in always the worst kind, and switches off the ability to ignore it. The night ushered in the foreboding morning. Spilt milk was worth crying over. I would step out of my front door over the top into No Man’s Land and face a barrage of information, incoming from all angles, from a wild unforgiving city that didn’t give a fuck about me and my pores.

So like the rich Victorians taking in the healing waters of Swiss spa towns, changing the nature of that information seemed like a good idea. I traded in carbon monoxide and horns for the smell of pine needles in the afternoon. A slanging match between a Turk and a crackhead became the quiet of a sleepy village waiting for its boulangerie to open. For six days the light hitting my face was no longer the pale glow from a screen.

And it went to work on me.

*

The gently rolling fields around Bordeaux are busy with backs bent-double over vines, tending to grapes like newborns. Warmed by the May sun, I move through them slowly, tasting the salt from my sweat and the creeping excitement of the unknown. Bastide towns and hillocks, copses and farm yards, pine trees and butterflies, the tarmac moves slowly backwards beneath my wheel and I breathe and whoop and feel it all deeply, the kind of attention I haven’t paid the earth in a long time.

I feel anonymous in a way I wouldn’t feel in England, there are no rules for me here, and this adds to my sense of freedom. I stop in Castillonnès and eat a simple lunch on the step of a deserted high street, a couple of locals pass by and commiserate about the weight of my panniers. In a shop window I see an old photo of the same high street, and imagine the day the man set up his strange contraption in the road and the shop sellers came out and the village stopped to pose, and think of the children that have lived whole lives since that day and grown old and been mourned.

I move eastwards into the Dordogne, the landscape ramps up, hillier and thick with forest. It is the oldest inhabited area of Europe and feels wilder than the vineyards and the roads are quiet. In 1940 while rescuing a dog who had fallen down a hole, a boy lit a match and illuminated the prehistoric paintings of Lascaux cave, releasing them from a darkness where they had lain undiscovered for 17,000 years. Casting his eyes on the paintings of bull and lion and rhinoceros for the first time, Picasso exited the cave and exclaimed in wonder we have invented nothing!

That afternoon a winding climb takes me up into the hills and I stop a while to rest. There are no cars, and all is still but for the breeze through the trees and the hum of insects. Lions stopped prowling these hills millennia ago but the landscape must look the same, I think. I am a fleeting visitor in an ancient land, I feel small and insignificant. More than that I feel lucky, to be where I am up on this hill, peering into this timeless kingdom for an eternal minute. I look at my bicycle lying in the ferns and nod respectfully. You and me mate. What else could have got me to this spot, shown me all this, made me feel so deeply.

I cycle on.

The Dordogne becomes the Auvergne. Harsh volcanic landscapes, sinister slate grey villages, even the weather changes to suit the mood. A cold front sweeps across France and I take shelter in cafés and massage my toes to get the blood back into them. There is sleet and snow and cold hard rain that chills me to the core. A techno festival 30km north turns into a Red Cross disaster zone. Some men in a bar convince me to fill my water bottles with red wine. One of them warns the others mais un litre de vin rouge… après on ne bouge…. They roar with laughter. It is not yet lunch time.

In September I stopped taking antidepressants for the first time in nine years. I was doing fine and wasn’t sure how much they were really working. Being med-free felt like a badge of honour and when I started feeling not so good towards Christmas I imagined it would last a month or so and then I would come out of it. But I never really did. I’d have spells of upbeatness, and show my face here and there, and then be back to normal. The trouble was my normal was a good few floors under ground.

*

On my way out of the Auvergne one afternoon, sat on a bench eating lunch, I heard a faint thud on the glass behind me, and saw a tiny man lying in a chair by the window beckoning me over. Perhaps the oldest person I have ever laid eyes on, his nose knotted like a 600year old oak, as he spoke his dentures fell from the top of his mouth and were caught by the bottom. He was very deaf, and after a few stilted sentences he fell silent, and grabbed my hand and held it.

As I cycled off down the road, a strange emotion surged up inside me, the kind of sadness that makes your tummy ache, that makes you feel so alive it’s hard to bear. When I was out of sight I stopped again and something dawned on me. Fuck, I thought, how is it that I can feel all at once so happy and so lonely. I realised I was coming back to life. All year my mood had isolated me, made me see so few people, I’d forgotten how to be in the world. And it had taken me 650km of French countryside to get to a point where I was happy enough to want to be in the world again, and a meeting with an old man to realise I had to start immediately.

Depression is the most narcissistic thing around, because it places you at the centre of everything. The world outside is beckoning you with open arms, and you can’t see beyond the four walls of your addled mind. Everything affects you, concerns you, hurts you. All information that comes in passes through the toll-booth of your depressed brain, which is too sensitive and defensive and afraid. The narcissistic part is the unending self-obsession.

Being in an environment so vast and ancient and eternal made me feel tiny and fleeting and insignificant. To be amongst those ancient hills and valleys and endless woods made me feel a tiny part of something bigger. My father complains that when I cycle I blitz through countries and have no time for cathedrals or museums. But the woods are my cathedrals, the trees are my spires, the cattle bells ringing out over the hillside are my evensong. Psithurism is a word for the sound of the wind running through the trees

*

On a rainy joyous day in early April interspersed with blasts of brilliant sun my brother got married to Victoria, and not long after my mood returned. My therapist did some rough calculations and we decided to go back on the meds. I was happy to in the end, I was fed up. It was taking the best of me. The roots of some trees run deeper than others. It takes something bigger to unearth them.

*

Looking down from the plane as it flew up and out of Lyon airport, I saw the small details of the French countryside I was leaving behind. Lines of roads, little hamlets, reservoirs, copses, all the signs of a country that feels alien to you because you will never know it. But I had known it. The chatter of the men in bars, the cool silence of empty churches, the town squares and looping mountain roads, the cattle bells and stillness of the mid-afternoon. I had known it all, and it had brought me back. Perhaps not altogether but enough. Maybe never in my life have I understood the wonder of a bicycle more profoundly, and its ability to show you the world in a way no other thing can.

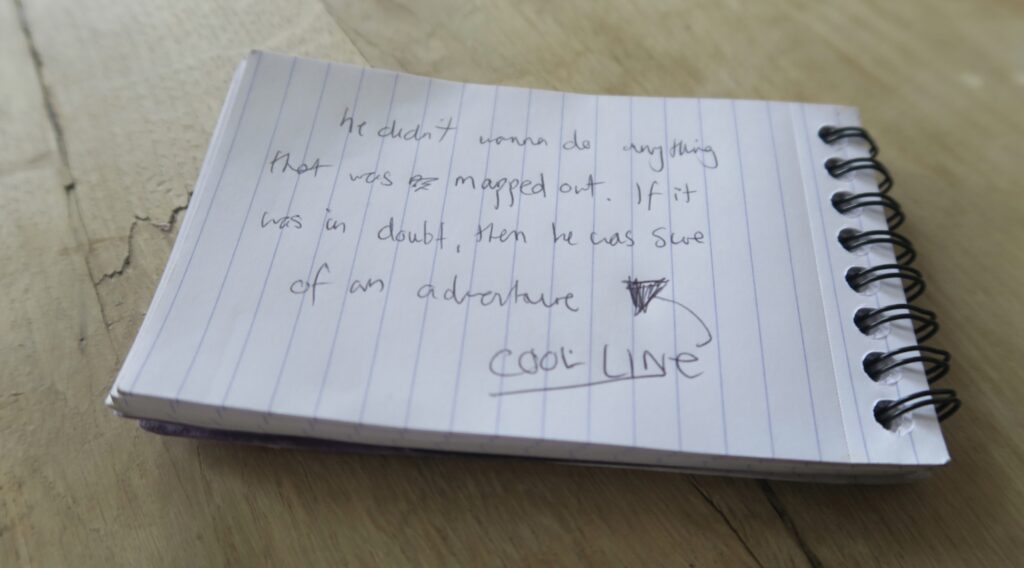

As we approached the first band of clouds, I took out my little pad to make a note, and flicking through the pages I landed on something I had written long enough ago to have no memory of it. I looked down at the scribbled words, read them slowly, read them again, and laughed.

He didn’t want to do anything that was mapped out.

If it was in doubt, then he was sure of an adventure.