Today is a Saturday of early August and after lunch, the Premier League season will begin again.

And because of this fact I am deeply uneasy, because I hate football.

I hate how boring it is. I hate how repetitive it is. I hate how easy it is to have an opinion about. I hate its baseness and cheapness. The lack of honour in it, the monotony and broken dreams, I hate Sky Sports Super Sunday, I hate how football sucks hours from my life. How it hoovers my emotions and churns them around and shits them out, I hate how try as I might I can’t help but be hooked by it.

Each summer, in between the polite applause and whispered gasps and cat gut thwacking nylon and leather on willow and the sweat and gears and heroism on Alpine mountain roads, at the back of my mind is the gnawing fear that the football season is approaching and the roar from the terraces, a murmur on the wind, is slowly finding form and gathering force like a wave in a distant ocean, and I fear its onset like a growing malaise because I know it will take the worst of me.

And so here we are.

*

The first intense crush of my life was Gary Lineker.

Not a football crush, a real crush.

I was six and he had come back from Italia ’90 and both him and Paul Gascoigne were playing for Tottenham, and as I gazed wide-eyed at the back pages of the newspaper I remember thinking how there could be a single person on the planet who wasn’t a Spurs fan was beyond me.

Three decades on I’m still a Spurs fan. As a journey it has been a non-starter, the car is still in the driveway, the keys broken off in the ignition. Without the highs the lows lose resonance, and supporting a team hovering around mid-table for a third of a century had come to warrant little more than a shoulder-shrug and the preamble to another drab weekend. Tottering Tottenham, they called us.

But four years ago something happened.

We started doing alright.

An Argentine manager called Maurico came in and some strange sorcery saw Spurs rising up the table, doggedly and consistently, and my dormant fandom began to reheat. All of a sudden I was six again, Gary was standing over my bedside beaming, I was all in. I learnt the fixture list by heart. I organised weekends around games. I’d sit alone in forsaken backwater pubs rifling through a ramekin of peanuts staring impatiently at the big screen waiting for the early kick-off.

I followed the construction of the new stadium as if it was my own kitchen refurb, I checked the webcam every two days for updates. I cycled up to N17 to tour the half-finished ground. I visited the Tottenham Experience to soak up the largest retail space of any club in Europe, I bought a jumper and a keyring.

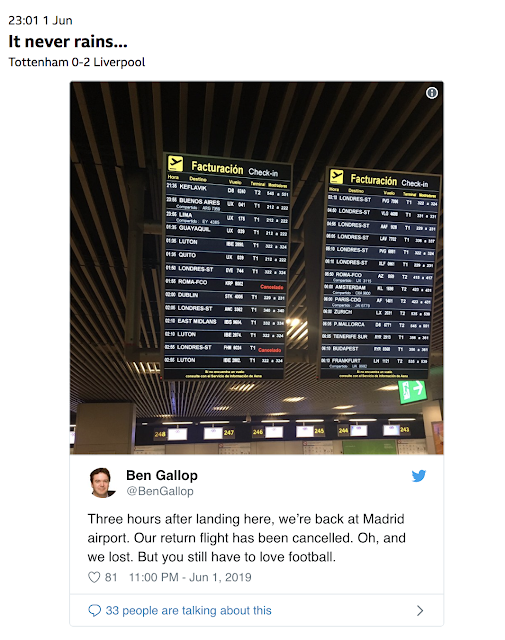

Things on the pitch were heating up too. At the end of last season Tottenham reached the final of the most important club competition in the world. Which was absolutely shocking. We beat the best team in the country in the quarter-finals. In the semis we came back from three goals down to beat Ajax of Amsterdam in the last minute of injury time. Spurs fans all over the world had heart attacks.

Mauricio fell to his knees at the final whistle overcome with emotion and later declared…

It is impossible to live without the emotion football brings!

I wouldn’t know.

Because I was in bed. I saw none of it.

At 2-0 down after half an hour I turned the game off. The same thing happened to me in the final, the biggest match in Tottenham’s history. I went to the stadium with 60,000 Spurs fans to watch the match beamed back from Madrid on six giant screens. 1-0 down with twenty minutes left but arguably the better side and still in the game, I slung my bag over my shoulder and walked out of the stadium. I turned my phone off and cycled back along the canal in the encroaching dark.

I couldn’t sit with the level of cortisol coursing through my body. I still can’t.

Each failed pass, each hopeless high ball, each bumbled set piece was more than I could take. As the seconds ticked by the dark mass of my mood metastasised, and prolonging it became so painful it overrode the prospect of any joy I might feel. I could no longer bear it, so what did I do. I forgot about football altogether. I put myself to bed, I walked out of a packed stadium, I unshackled myself from pain.

And with it I lost any chance of feeling pure ecstatic joy.

There is a strange thing about sport.

The investment in it. The reading of articles, the scanning of statistics, the buying of merchandise, the amount of time spent caring in something, the outcome of which you have no control over whatsoever. The only control you have is in how much you choose to care, at what point you choose to walk away. It is a love affair.

The day I went to the Spurs stadium to watch the Champions League final taught me something about football I’d never experienced. In the hours I spent around the ground in the build-up to kick off on that early afternoon of midsummer, I saw an outpouring of human emotion such that it changed the way I saw the game as a whole.

What happened on the pitch was a sideshow.

I saw six hundred fans outside a pub jumping in unison for forty five minutes spraying fountains of beer all over themselves. I saw a man up a lamppost being cheered by an army of three thousand. I saw a four year old screaming YID AAAAARMY at the top of his voice, exploding with pride. It was joy and passion unbridled, something tribal. It was human connection.

As a dad and his two kids made their way through the cacophonous underbelly of the stadium, I went up and asked him what it felt like to be bringing his boys to the ground, to be passing on the baton. It’s different, he said. Do you wish you were in the mad throng of six hundred, stomping in unison, drowning in beer, I asked. He looked at me deadly seriously. I was mate, I am.

The true DNA of football runs through the heart of working class families, generations of football fans, born into a love for it who grow up with it in their blood and pass it down. Who go to cheer their team every match day and its resulting triumph and disaster and treat those two imposters just the same. Who proclaim their love to their losing side at full-time just for getting to a final.

Who the hell walks out of a Champions League final with twenty minutes to go. I can’t call myself a real fan. Real fans are all in, regardless of pain. That’s what love is, being all in. Football isn’t about winning. It’s about investing your love in something through the highs and lows, and being unconditional.

How should we like it were the stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

To be half in, only to guard oneself against suffering, that is no life.

So how am I set for the oncoming season.

The other thing about life, I suppose, is sometimes you just have to let it happen.