At the end of 21 Grams there’s a Sean Penn monologue about the weight of the human soul. Which starts with the line.

How many lives do we live. How many times do we die.

Watch it, it’s beautiful.

With the exception of light at the end of the tunnel experiences spoken from hospital beds, or coffins with scratched ceilings, or reincarnation, I think we must only die once. In terms of the heart stopping and the soul escaping and the flesh rotting. The dust to dust idea.

I’ve always been drawn to things that we can’t understand or explain, maybe for the reason that we can’t understand or explain them, and up until recently when it came to the idea of the next chapter I was happy to sit on the fence with the sun on my face dangling my legs in the late-afternoon breeze. But strangely, these days I find it hard to believe in an after-life.

I think I agree with Bertrand Russell.

When I die I shall rot, and nothing of my ego will survive.

But why should we have the arrogance to assume that only logic and science within the spectrum of human understanding is what is actually out there. There is an argument for the existence of God based on ants. It runs that if ants can walk the earth in their billions unaware of the existence of us, the self-styled omnipotent species of earth, then equally why should it not be possible that something greater than us should exist outside the spectrum of our own understanding.

It’s a question that has polarised humanity’s best minds. One of my most rational friends and father of three months Gregory Kennaugh from Putney believes that we must hang around in some form or other after the landlord finally kicks us out into the cold. Einstein was a fan of mystery too. This coming from a man the sum-total of whose credibility rested on nothing less than absolute conclusive proof.

I know one thing. That at some point in the future, certainly bedecked in boxfresh AF1s…

I will wax from the pulpit about the certainty of an after-life.

*

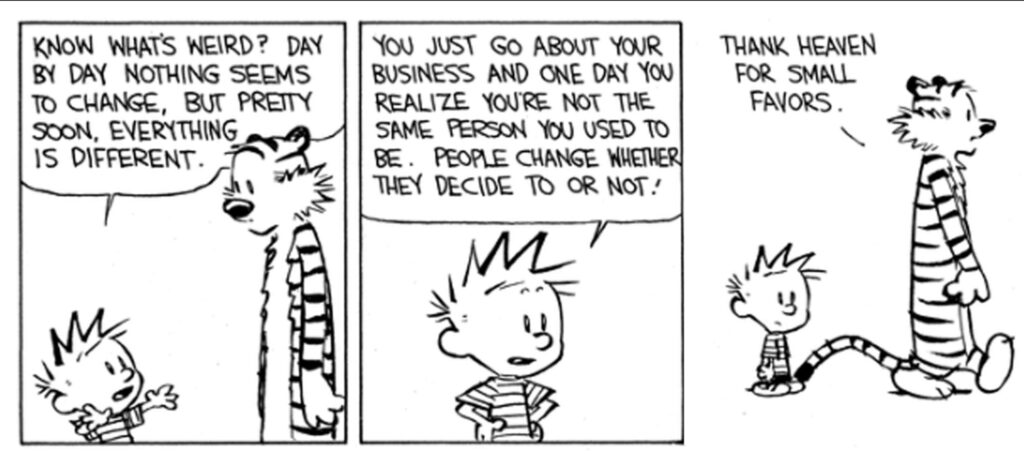

The after-life quandary is just an example of how our opinions on things change in relation to the different stages we are at in our lives. Anyone who has reread old diary entries and looked perplexed as they see a page written in their own hand-writing, spewing forth thoughts that could never possibly have come from their mind, will acknowledge how much our brain can change. Not just a particular opinion. But a complete outlook.

Just as spring eventually loosens winter’s grip and autumn pulls down the blinds on long heady summers, over the course of our life we will encounter change, not just from the outside but from within. Right now, despite its insistence on remaining tediously cold, spring is changing everything in our natural environment. There is a continent-wide shift in play.

We too are the trees through the seasons.

The trees themselves, their whole entity, they don’t change. But over the years their trunks will morph and fatten, their branches will grow out in different patterns shaped by the wind, they might be felled in storms or pruned by zealous park-keepers, and every year their leaves will spring and bask and die and fall. The trees are always changing, yet somehow aren’t.

I think it works as a metaphor for how we as people change. Those who maintain that people never fundamentally change are both right and wrong. Like the trees we are capable of change and yet incapable of it. We are the tree, but we are also its morphing trunk and falling leaves. And just like the tree, our lives are made up of seasons.

The Wonder Years was great because it pitched the idea of simultaneous time. The mature narrator, speaking to us from inside the mind of a teenage Kevin, was a reminder that time doesn’t have to be linear, that the different stages of our life are interconnected and playing out simultaneously.

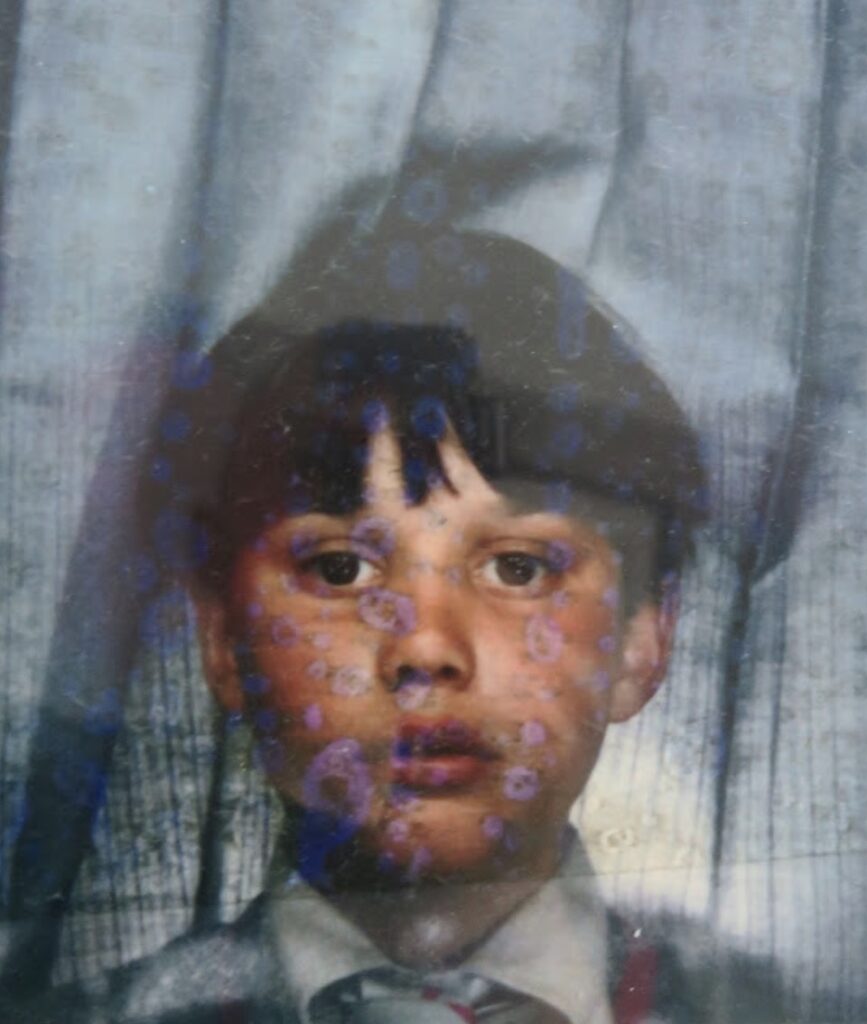

I’m reminded almost every day how connected I am to the six year old inside me. I’m looking out for him all the time, I’m still fighting his battles, I still feel his pain. If I stretch my imagination I am also connected to the 75yr old in me. He’s studying me quizzically right now by the fire in his carpet slippers, watching as my actions and today’s life choices form the tapestry of the life he has to look back on.

Old age is staring me in the face in a more real way too. In the form of two of the people closest to me in the world. As my parents move towards the music and take the floor in a slow-dance with their mortality, I realise they haven’t changed. They’re still the same children whose blurred photographs stare back at me from old photo albums, the same expressions of joy or boredom or surprise spread across their faces.

They mean the world to me because I love them. But to the outside world they’re anonymous people in the autumn of their lives. There’s an old lady in my local Tesco who regularly holds up the supermarket queue to talk to the cashier, much to the ire of the line groaning under the weight of their baskets. But it could be the only conversation this lady has all day. She might have lost a few braincells, but she was also probably the matriarch of a large family. In her prime she had guys queueing round the block just to speak to her. She has seen all of life. She demands our respect.

*

Same as Alf, regardless of where he posts his letters.

Old people are us. Because one day, we’ll be them. If we don’t respect them we disrespect ourselves. And the cycle of life that we are involved in. I wonder if this trigger-happiness to dehumanise the old is something we need to start checking ourselves for. Why should it take a leap of imagination to think of old people as young once? Is it not all part of the same grand arc of life. Just as the leaf grows hesitantly out of the branch, dances for a while in the summer breeze before turning brown and falling to the ground. Alf could tell you that.

Funnily enough Alf is the lead character in all of this. I’d send him a letter, but I’m not sure he’d know how to return it. Oscar Wilde said that the tragedy of old age was not that one was old, but that one was young. Alf is all of us, by reminding us that one day we will be just like him. We are all connected. Young and old are all the same.

This doesn’t change because we sprout nose hairs or start to feel the force of gravity weigh more heavily on us. It doesn’t change because the distance to our feet can feel unbreachable when the time comes to put our socks on. It doesn’t change because we post all our letters in the dog poo box. We’ll still feel the same inside as we did when our bodies worked without a second thought. Our parents would be the first to tell us that.

*

At the end of Prufrock, a 22 year old T S Eliot writes from the perspective of a man both looking back on his life, whilst wondering what old age might bring.

I grow old… I grow old…

I shall wear the bottom of my trouser’s rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

*

We can start singing, even if the mermaids won’t.

We can at least remind ourselves to from time to time.