Giles Coren is best known as the angry man who writes scathing reviews of restaurants. But some years back The Times gave him an opinion column on Saturdays from which to pontificate over things above and beyond the culinary.

Yea exactly.

But one idle Saturday of early April Giles ripped up the script. In my time as a seasoned attendee of the broadsheet milieu I can put it down as one of the most pleasurable reading experiences of my career. I felt the need to tell him. He said ‘thanks’.

In defiance of Murdoch’s paywall I Assange’d the situation and transcribed the thing last night while my mate stood me up at the pub. And I can’t type very fast. It took me ages. I even threw in some pictures to season the sirloin.

*

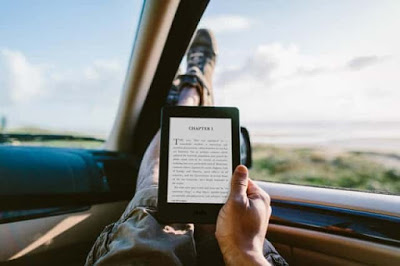

Leaving aside such tedious familiar responses as “me wife” and “me kids” and “me ‘elf”, the most important thing in my life is my Kindle. It’s not just that it has doubled the number of books I read in a month and tripled the number I buy – doing immense service both to my brain and to the coffers of a desperate publishing industry – nor that it has rid my walls of decaying organic matter, nor even than it has revolutionised my packing for holidays, creating a space in my luggage where 20 paperbacks used to be that can now be filled with budgie-smugglers in every imaginable hue. Above all, what my Kindle has done is give me a new way of reading and thus led me to new ways of thinking.

For most of my life, I read one book at a time. The old-fashioned textual delivery method encouraged a teleological commitment that drew one inevitably to the end of each book before starting the next. But since moving wholesale to electronic formats, I find myself reading at least two, but more usually four or five books at once. I always have one vast work of non-fiction on the go for reading on public transport, alone in restaurants and while sitting on the sofa watching Tom and Jerry with my children (when distraction is called for, but plots cannot be followed). And also a modern, ambitious literary novel for a quiet hour in bed before sleep, when the deep, private part of the brain can be fully engaged.

Then I have usually a collection of letters or diaries standing by to offset the tedium of the morning stool and some sort of cheap sadomasochistic pornography for lonely nights in provincial business hotels. Add at least one awful book by a friend that has to be ploughed through for a single nugget of praise that can be delivered without actually laughing, and you have five books being read at once in a sort of literary jigsaw that previously never existed. Certainly not in a portable form that could be accessed without plan or forethought and with a single unifying typeface, page size, colour and heft.

And what happens then – which is quite fascinating – is that these unrelated books begin to read to and against each other, existing as they do almost simultaneously in my imagination, and to make new books that did not exist before and generate ideas their authors never intended. So i found myself reading Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers: The Story of Success at the beginning of this year alongside the third volume of Fifty Shades of Grey, and thus endlessly musing on why one person should come to be confident and accomplished at rough sex, and another not. Genetics or education? Practice or natural gift?

I read Stephen Grosz’s The Examined Life (a collection of psychoanalytic case histories) page for page with Ian McEwan spy novel Sweet Tooth, at times when Will Self’s giant neo-modernist riff on mental illness, Umbrella, was more than my head could handle, and found myself unwittingly formulating a psychoanalytic model for the causes of the Cold War that would blow your mind. And a simultaneous reading of Bring Up The Bodies with Claire Tomalin’s life of Dickens, Charles Moore’s Thatcher biography and the letters of Ronald Reagan gave me a massive new story of how public power has emerged out of individual solipsism across five centuries.

This is the post-structuralist dream of the truly free text, unhinged from all notions of authorial intent and cultural location, at play in the world in a Derridean loop of self-generated semantic crisis. This week it reached its apogee for me in a simultaneous reading of Max Hasting’s Catastrophe: Europe Goes to War 1914 and Dave Eggers’ The Circle.

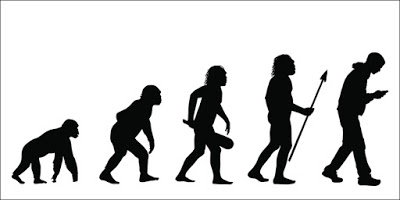

It is hard to imagine two more different books. One is a vast, rather butch anatomy of European politics in the run-up to the First World War and the slide towards mass slaughter, the other is a slim American science-fiction novel rooted firmly in the 20th-century dystopian prophetic tradition of Orwell, Huxley and Wells, set on the campus of a Californian technology company that has already consumed Facebook, Twitter and Google and is on the point of “closing the circle” so every lived moment is accessible online and all human activity is controlled by an invisible, omniscient, commercially motivated will. But both, I suddenly realised in bed last night, are about the same thing: humanity rushing dumbly towards its doom.

In 1913-14, the world stood on the brink of a confrontation in which the old would collide with the new in a most horrific way. Modern technology – originally developed with the best of intentions – would sweep away a generation that had rushed eagerly into the fray, polishing its new boots, winking at girls and singing It’s a Long Way to Tipperary. All that was good and sound and beautiful would be lost because nobody thought the worst could happen and once it had started to happen nobody had room to manoeuvre out of it.

We stand there once again, exactly 100 years later. On the brink. The shift of everything we know – communication, social interaction, sex, shopping, sport, morality – from the physical to the digital universe is happening so fast that it is now out of our hands. The world we knew is in its death throes. The lamps are going out. Our young people are marching off into a future where every single element of their life is filmed, phoned, liked, poked, tweeted, retweeted, slapped… (I begin to run out of terms and sound old and fatally disconnected) and every facet of human existence is validated exclusively by its digital mediation (even I am aware, for example, that this rather esoteric* column will not attract the attention I get with one of my “ban all triangular things and lock up the Belgians” pieces, so will not make the “most read online” league table come Monday morning, and will be judged therefore as worthless by our marketing department).

I see young people, shackled to their phones and tablets and their lifeless jobs of pointless information-sharing and I see lions led by donkey Zuckerberg, the donkey Gates, Jobs, Brin, Dorsey and Wales – whose names will live in infamy alongside Haig, French, Rawlinson and the rest – sending millions of young men and women to their doom in the blind service of their own reputations and fortunes. A whole generation brainwashed not by the twin mirages of king and country, but by something else altogether. Though I am too old to understand what it is. Connectivity?

It does not have an anthem to lament it, this doomed youth. But I see young people at restaurants, in pubs or at the cinema, hunched over their flickering interfaces, pissing their very lives away, and I think, “bent double, like old beggars under sacks… an ecstasy of fumbling… his hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin…” They churn and moo outside their schools, grazing the internet for tiny molecules of sustenance and I think: “What passing bells for those who die as cattle?”

There isn’t any turning back now, as there was not 100 years ago. And just like 100 years ago there are vested interests, in cold alliance with lazy thinkers, telling us to stop worrying, it is all going to be fine. But it wasn’t then. And it won’t be this time either.

[If you spotted the grand irony that i only arrived at this gloomy realisation through the technological advance represented by my Kindle, congratulations. But i never meant to suggest technology was useless, only that it is murderous.]