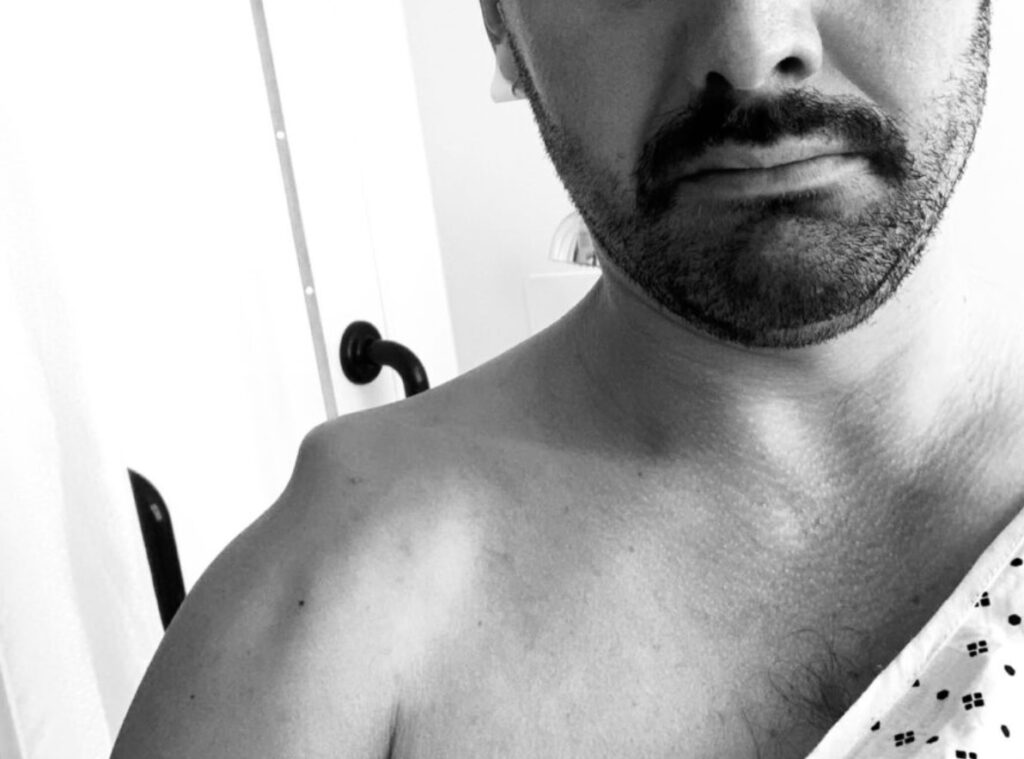

Lying in hospital at 2.43am on a drip, I figured the only way was up. I almost shrugged a shoulder but thought better of it. For a week the only thing holding my collarbone inside my body had been skin, my left wrist was a mess.

From on high a zen descended.

When you go down with 50kg of loaded touring bike under you it’s always dramatic. I’d brushed myself off, saw blood and road rash down my leg and elbow, felt an adrenaline surge to mask the pain. Close run thing. I went to pick my bike up. It dropped like a stone, no strength in my arm whatsoever. I reached for my right shoulder and a bone the size of a golf ball I’d never felt before was pressing out of it.

I hung out with some horses for half an hour, a plump lady rounded the corner, I flagged her down with my good arm. Je crois que j’ai cassé ma clavicule, I said. She looked horrified. Oh mon Dieu. She reversed onto the grass and lit a cigarette.

The ambulance took another 45. A legend called Habo, a military doctor who’d pulled up in his jeep, kept giving me counting exercises to do to stop me fainting. When the Pompiers loaded me into the back and barked at me to stop fretting about my bike, Habo was like bro chill, I’ve got it. He called me most of the afternoon to check on me.

After seven hours in a hospital in Limoges watching people being wheeled into A&E in ten times worse condition than me, they sent me away with no pain medication for one of the worst nights of my life. My wrist was fractured, my collarbone was three inches out of position, I couldn’t take my cycling shorts off to pee, and lay on the bed of a hotel room in filthy sports garb sweating out the pain, thinking of large women.

In the morning I limped to the pharmacy.

Nothing rams home the information you should probably get a girlfriend faster than your mother flying out to France to carry your bags back for you. Gap year stuff.

The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft a-gley

Robert Burns

Back in London a surgeon told me my shoulder separation was a bad grade 5. What’s grade 6 then, I asked. Not much shoulder left. I asked him about the odds of attending a festival in Somerset the week after the op and he cracked up.

It killed me.

I’d been looking forward to the trip for months. Heady summer days stretching out before me like a never-breaking wave and in twelve seconds my plan A had spontaneously combusted. Plan B didn’t exist. If I hadn’t been focusing on the half-cow I was going to take down for dinner maybe I would’ve seen the oil patch, maybe I’d be free-wheeling down a mountain like a gee instead of sat in a hotel stinking of BO and regret.

With a week to go until the op I fell off a cliff. Alone in my flat I sprung for a Huski beer cooler and got totalled on ludicrously cold pale ale. The morning after brought with it bad news. A headache, a messed up shoulder, and the malaise of the other two put together, I saw a summer slipping out of my grasp.

*

CHINESE PARABLE TIME

In olden times, a Chinese farmer’s horse runs away. That evening his neighbours join him to commiserate. We are sorry to hear of your horse. This is most unfortunate. Maybe, says the farmer. The next day the horse comes back with seven wild horses, in the evening the neighbours return. What a turn of events, you have luck on your side. You have not one but eight horses. Maybe, says the farmer.

The next day attempting to break in one of the horses the farmer’s son is thrown off and breaks a leg. The neighbours crowd around, commiserating. What bad luck. Maybe, says the farmer. The day after officers came to conscript soldiers into the army for a Great War, they scour the village but leave the son behind on account of his injury. What great fortune! chime in the neighbours.

Maybe.

*

Chaperoning me back to Hackney after the operation my bro buys me food from the supermarket, makes sure I’m chilling and leaves. The door shuts and I bend over-double, break down. Sob hardcore. I feel pathetic, I drain my tear ducts. Weirdly once I think I’m done, I go again. Intense cartoon-like bawling. Some almighty build-up of tension releasing itself.

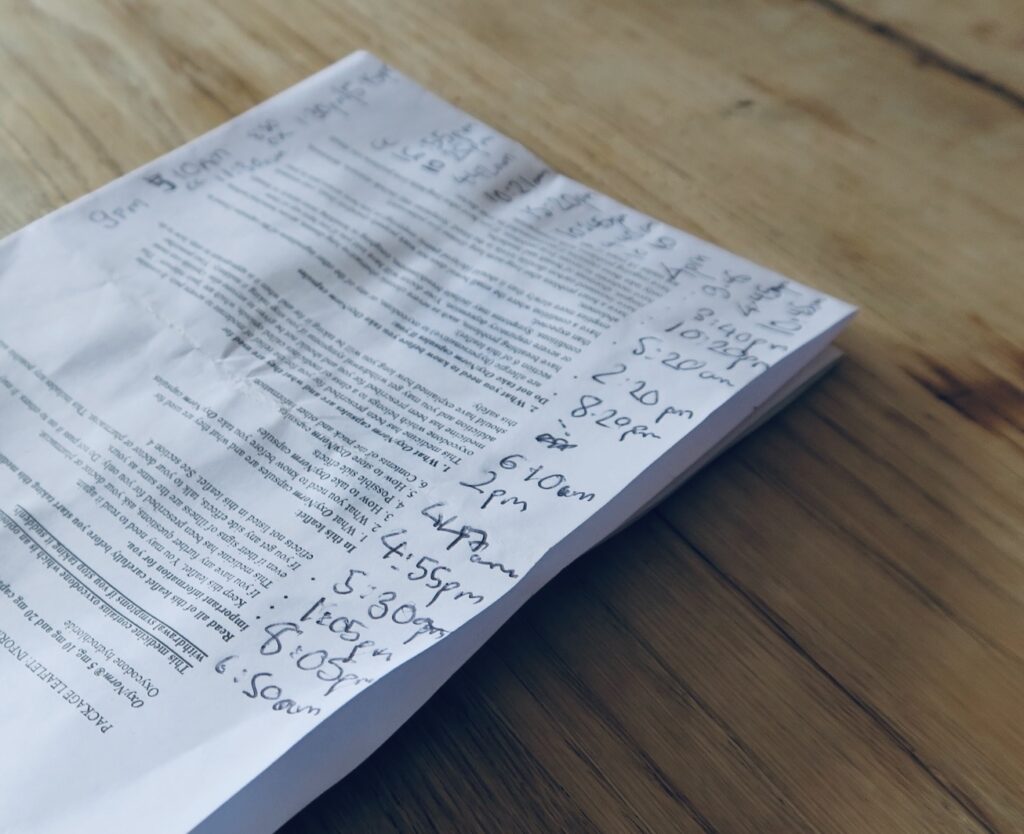

I spend the next week staring glumly out the window, noting down my cocodemol so I don’t overdose. On a nurse’s instructions to allay the plugging up of bowels from illegal amounts of codeine, I up my fibre intake and slam Weetabix for the first time since ’91.

I think back over the last month.

Makes for strange reading.

I’d been mugged by some dodgy guys in the back of a Merc. Two days later half my bike gets stolen. An oil patch rules me out of a great adventure, a best mate’s 40th, and I sack in a ticket to the world’s greatest music festival. Spurs finish 8th. In a hotel in some French town I suffer the ignominy of not being able to wipe my arse for two days.

Am I being tested.

On the phone down to LG, I search in vain for the moral of the story. There doesn’t always have to be a moral you douche! he says laughing. There’s always a moral, I clamour. I call a Deliveroo driver an idiot over text. I’m not wrong. Refuses to find my flat even though he’s a minute away. Still it haunts me.

To atone I pick up three Huski beer coolers for some cold-gold obsessed mates. Yesterday a salt of the earth dude takes the Amazon package from outside my door before I can get it.

I am being tested.

Sometimes rock bottom is your trampoline.

Job-like I rail at the sky.

THIS ALL YOU GOT BRUH.

When God takes everything from Job and Job asks why are You testing me, God shows him the infinite complexity of the world of His creation, and says you have no idea the things that are at play, in every minuscule moment. My shoulder situation was shit. Or was it. Maybe. Like the Chinese parable, who knew what weirdness might come my way, in this newfound situation, not in spite of but because I had gone over my handlebars, halfway up a hill in France.

The guy who told the parable, Alan Watts, went on to explain. The whole process of nature, he said, is of such immense complexity, that it is impossible to tell whether anything that happens within it is either good or bad. Seeing as one can never tell down the line what might be the consequence of good fortune; nor the consequence of misfortune.

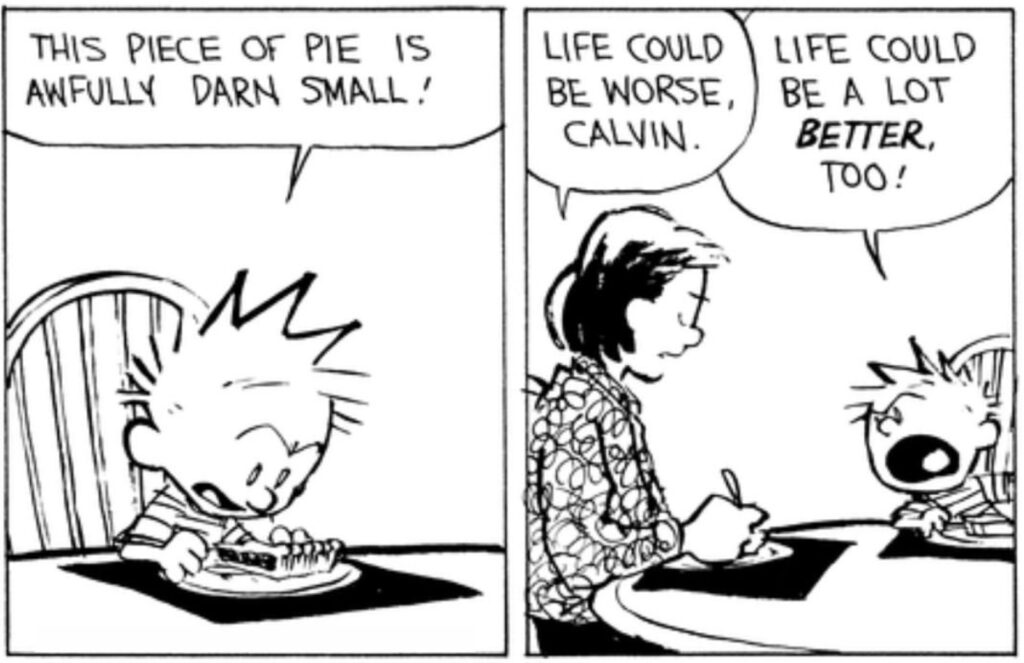

Mulling this over on my eighth cocodemol of the day, I figured things could be worse. Then again, who was I kidding, they could be a lot better too.

Maybe a summer of sitting on my tod knuckling down, healing, finishing a book, making podcasts, reading good shit, doing things I didn’t want to but were beneficial to me, was better than what these months of balmy evenings tended to encourage, impulsive pleasure and Gatsbyesque hedonism. Far-fetched, but not out of the question.

What if everything right now, was mysteriously perfect.

You know what’s better than feeling superb. Summoning a smile when shit goes south. Laughing in the face of aridity and disenchantment. When things get really bad, that’s when you take the stage, do a little jig.

When life gives you lemons you paint that shit gold.

I’d hurt my shoulder. But I was no man in the iron lung, lying in a yellow box since 1952, all the while insisting his life was perfect. If you wanna find someone worse off than you, you don’t have to look far.

My shit was laughable.

Just as well really.

The surest sign of wisdom is a constant cheerfulness.

Montaigne

It sounds pathetic, but those two days in the hotel, when the pain in both arms got so bad I couldn’t even take my socks off, the night I’d spent when the only movement not making me wince was opening my eyes, showed me something humbling, about a state of survival. As if when things are really bad, all you can do is breathe. There’s no space for sadness. It’s just onto the next.

Reduce your time span. Get through the next five minutes.

*

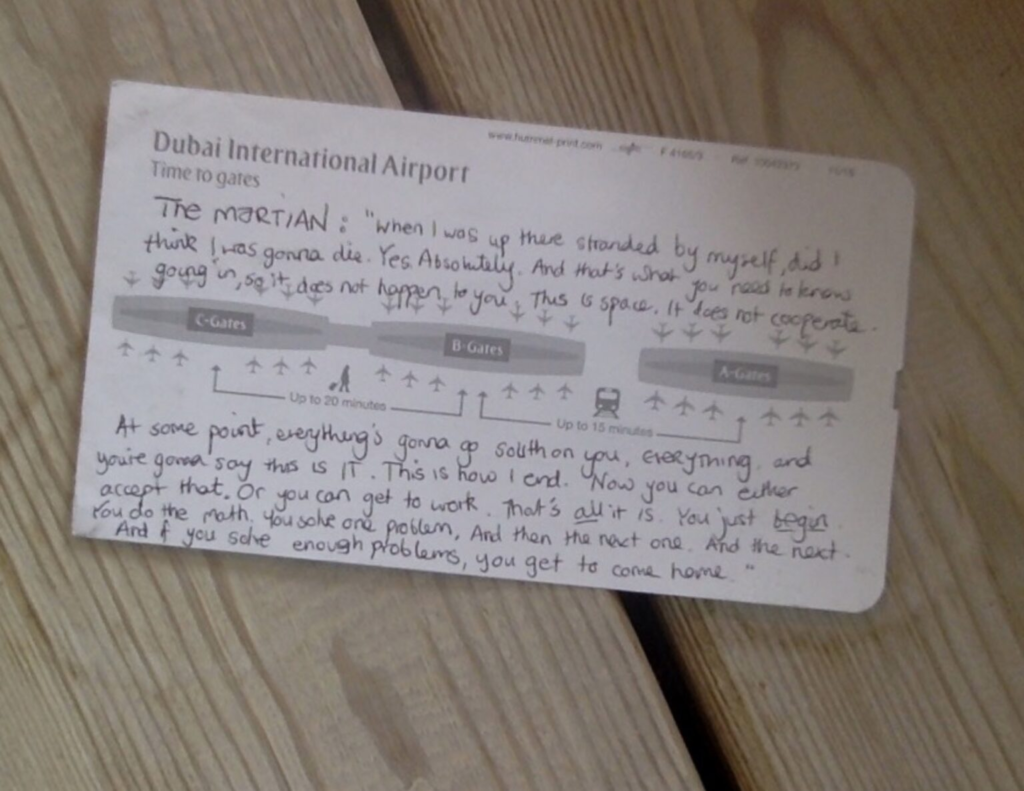

The end scene from The Martian, that had flipped my lid so hard on a plane once I’d copied it onto my boarding card, came to mind.

This is space. It does not cooperate. At some point, everything is going to go south on you. Everything is going to go south, and you’re going to say.. this is it. This is how I end. Now you can either accept that. Or you can get to work. That’s all it is. You just.. begin. You do the math, you solve one problem. Then you solve the next one. And then the next. And if you solve enough problems you get to come home…

Feeling miserable invokes a certain leeway, a space, a gap within which to feel sad. But when things really go south, all you can do is get through it. Get to work. Solve one problem, then another. Put out fires to get you through the day.

I would’ve learnt none of this had that road had no oil on it. I would’ve had a nice holiday and some high-end steak, got a ropey tan-line and gone to a banging music festival.

At the end of Eternity’s Gate, in a passage from one of his letters Van Gogh turns to the man he is painting and says an angel is never far from those who are sad.

*

So that’s me.

Spouting philosophical garbage tripping balls off codeine, doing the next best thing, counting blessings, listening to unhealthy amounts of some low-end podcast. Life could be better. Life could be a whole lot worse. When it gets better I’ll calculate if deep down, all things considered, things are even better after all. They might be.

Maybe.