Up in the high Andes, freezing to death inside the fuselage, their own bodies eating them alive, many of the boys from the Old Christians Rugby team said they came face to face, not with the God of scripture, the one they had learnt about at school, but the God of the mountain. A different type of almighty force. Many of them once back at low altitude, began to question their Christian faith.

What is God.

I’ll take a shot.

*

If God did not exist it would be necessary to invent him.

Voltaire

In a witty reparti Ricky Gervais says to a believer… you deny one less God than I do. You don’t believe in 2,999 Gods, I don’t believe in just one more. I mean he’s right. There are more Gods around these days than savoury donut options.

What all believers tend to converge on is the idea of a force above us, a higher power. Be it the Hindus, Muslims, the tribes of Africa, the Greeks and their myths, the God of fire and brimstone from the Old Testament. The thing that atheists scorn, with good reason, is the inconsistency of these theories.

They can’t all be true.

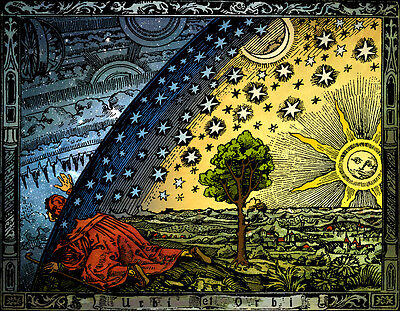

A good definition of God describes a circle, whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. The everything the light touches Mufasa moment. On mushrooms one morning in the flat as the sun streamed through the big school windows I found it very clear and obvious that this had to be it. The light glinting off the eucalyptus, the sway of the branch in the dawn breeze. Mufasa was right.

God was everything, everywhere, all at once.

David Foster Wallace was famous for a joke he made at the beginning of a commencement speech, two young fish are swimming along, and they meet an older fish who says morning boys how’s the water. They swim on a bit and one turns to the other and goes, say…what the hell is water. The idea that some of the truths that surround us are so glaringly present, hidden in plain sight all around us, we don’t even see them.

The limitless circle.

I could tell you my journey to cracking the God-shaped nut started around two years ago, with an experience, but most probably started far before that, in the scratchy feel of a First Communion suit. But sometime in 2021, lying on my sofa somewhat under the influence, something broke the fourth wall of the world and shook me to my core, opened a door that said, anything and I mean anything from now on could be possible. I called my father the next day in tears, telling him I’d had a religious experience. Don’t tell your mother he said, she’ll be worried.

I started to look for signs.

The fact you’re looking for a sign is the sign you’ve been looking for, I saw stencilled on an electrical box off Redchurch St. Looking down one day I saw a small cross on a pavement, I picked it up and took it home, put it on the kitchen island.

I became one of those bores putting their fate in the hands of the heavens. I tried calling a girl one day I was working some magic on and couldn’t get through. It’s a sign, I said to Alfie. Yeah mate, it’s a sign she has no phone reception. Also mate why is there a tile-divider on your table.

*

The problem with this God thing, the problem in Gervais’ demand for proof, is a demand for the impossible. One cannot prove It, Him, Her.

Since the enlightenment, the advent of Science and the ushering in of rationality and materialist reductionism, the human mind has worshipped at the altar of proof. Anything invisible is fantasy, hallucination. The confidence in this scientific viewpoint is bulletproof.

God is an illusion.

There were so many things they didn’t understand, not that they were dummies, explains Sean Carroll, so they had to come up with the idea of God. As we understand things better and better, some things stick with us, some things get replaced.

Very succinct, Sean.

As damp-squibby as this sounds, the God debate basically comes down to the left and right hemispheres of the brain. We are tilted either towards the left hemisphere, the problem-solving, logical, survivalist one, or the right, the realm of the artist, the one letting in information from all angles. Both work in tandem with each other, but as people we tend to either look left or right.

Those at the coal face of understanding existence, are the physicists and the poets.

Iain McGilchrist

The atheists, simply put, are left brain people.

The believers skew right.

The problem for the rationalist is this. While not much can make the brain more left-leaning, swathes of experience can open up the right hemisphere. Fasting, meditation, repetitive dance, psychedelics, down-regulate the default mode network, allowing the brain to make connections it would otherwise be fenced off from, the circuitry twinned with awe and belief in something far greater than ourselves.

This was all more self-explanatory back in the day. But since Galileo got airtime and Newton and Darwin began propping up the bar, as a culture we have been skewing more and more left. The same thing happened to the Romans, they became governed by logic and reason which eventually, writes Iain McGilchrist, led to the crumbling of the empire. This emphasis on the left hemisphere is the same outlook which now brings on the swatting away of religiosity, the derision of religious nuts, of God being no more than an illusion.

But look at Cindy.

Anybody who grew up with a postcard of Cindy on their pinboard doesn’t need to look far and wide for proof of the existence of a Creator. The big man in the sky wasn’t messing around. Jung said people don’t see God because they don’t look low enough. Asked in an interview about the state of his belief, he replied famously…

I know.

Truth, love, nature, God, they might all be synonymous words, interchangeable. The problem with the left brainers is they don’t like not knowing. They’re not content with it. So they refute. Prove it, they cry, cranking up their bunsen burners from behind the safety of their safety specs.

But nobody knows.

Not even Jung was laying claim to objective proof. More like he knew, rather than he knew.

Logicians and theologians talk until blue in the face, the argument by design, the ontological argument, the cosmological argument, the argument by gradation, God of the gaps, back and forth, back and forth. My brain is too low-rent to keep up, as interesting as I find it all, but I come back to the same point.

I could not deny what had come knocking one day.

I just didn’t know where the hell to put it.

My experiences of synchronicity, of strange events that went beyond serendipity, Jung’s most famous and far-out theory, had made me believe I might be in a mysterious dance with the Universe, but also some might contend, one step closer to some high-end psychotherapy.

In my floaty looking for signs way I stacked my chips on the empty cabinet on my bathroom wall, decided if this was all real I’d open it one day and find something miraculously in there. A VIP invite upstairs. I checked most days. There never was. Drunkenly I might launch into a monologue about it all, friends would listen politely. I’d written a prayer to my own version of God when I was 25 and especially happy, which I would recite midway through runs looking out over the Lea river.

Questions poured down like spring rain.

On the tube once, sat there sadly one evening opposite a group of youths about to hit the town, the train stopped and one by one they got off talking loudly. One among them, a cat with with long hair who’d been peering my way intermittently, stopped in front of me and looking me steadily and kindly in the eye, told me Jesus loves you. I nodded, half-shocked, half-moved. Really, he repeated, running off through the doors as they were closing.

Telling my ex-girlfriend this, she sat up in bed one morning and said very seriously in an almost strained way, Domingo if you feel some pull you have to go towards it, with everything you’ve got. I half nodded, but still it scared me.

I suppose the gap between one person and the divine can be bridged only by the person themselves. What is meant by the leap of faith. The one Indiana Jones nailed at the end of the Last Crusade.

That, or the Divine comes and slaps you round the face E. Honda style.

Some things I’ll keep to myself.

*

I don’t believe in God, but I miss him.

Julian Barnes

We find ourselves now in the 21st century, at the helm of the first society in human history to have ever lived without some idea of God, and something else is coming in to fill the void. Something has to sit on the throne of the culture, says the writer Paul Kingsnorth, and if it isn’t God, some other thing will rise up in its place. Reason, economic growth, technology, self-promotion, a new worship not of God but of the self.

Foster Wallace agreed.

In the day to day trenches of adult existence, there is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of God or spiritual-type thing to worship is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

If you worship money and things — if they are where you tap real meaning in life — then you will never have enough. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you. Worship power — you will feel weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to keep the fear at bay. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart — you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. And so on.

David Foster Wallace

The wars of religion, the Crusades, Jihad, the bastardisation of faith by man, the argument atheists bring up with good reason to counter the blood religion has on its hands. The race of men is failing, wrote Tolkien on Middle Earth. Onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war, screwing up the sacred, twas ever thus.

We might be beginning to find out, Douglas Murray says, that the only thing worse than religion could be its absence. God, this thing the human mind is more or less incapable of explaining, is being replaced by something far more unstable and maybe more destructive.

Murray goes in hard.

Looking at the great cathedrals of Europe, Michelangelo’s frescos, Bach’s concertos, it is hard to believe the motivating force behind this was some sort of un-informed superstition from pre-enlightenment simpletons. Apparently the last highpoint of the human brain was the Renaissance. When God was the man about town, showering down his gifts while mankind stammered back art worthy of his grace.

In Judaism it is said one cannot explain, but only attend. They have such a healthy fear of God they cannot even mention the word. G-d, they say. Another way of attempting to conceive what is inconceivable, Ram Dass explains.

If this is sounding quite noncommittal, it’s me understanding how little I understand. I’m in good company. At the end of his life Thomas Aquinas admitted that all of his writing, the totality of all he had dedicated his being to, the work of a lifetime, these words were.. ‘as so much straw’.

*

I wouldn’t be surprised if God made himself understandable to the demographics of the world by making himself relatable to their culture. The Buddhists and Atman, Taoism and their Tao, the Muslims have Mohammed and their laws. The African tribes. The Native Americans. The big guy moves in mysterious ways, the burning bush, the immaculate conception, Maradona’s hand.

Funny that the one guy who pitched up in Israel 2,000 years ago seems to play a part in them all. The Buddhists recognise Christ as the only other incarnation of God besides Buddha, the Indian mystics talk of Christ consciousness, the tribes of the Amazon described visions of the Virgin Mary with no knowledge of Catholicism, in Judaism and Islam he was a wandering prophet.

Tom Holland of The Rest Is History fame recently wrote a book called Dominion. Similar to the Foster Wallace water metaphor, he said we are goldfish in a bowl swimming in Christian waters. His study of the Greeks and Romans had led him to believe our morality, our ethics, began 2000 years ago when some guy with a beard and some strong opinions rolled into town.

The question I didn’t want to ask I suppose, paddling around in my right hemisphere dream pool, is how much of God is merely us, a yarn spun out of our infinitesimally complex brains. Why did my buddy Raymond’s mother eat chocolate mushrooms by mistake and see visions of Shiva and Krishna, in keeping with her faith, rather than the Buddha or Mohammed. Is it all just a projection of our minds, was Sean right. All an illusion. But why do we have a capacity for religious experience in the first place, what is its point.

What in the world is going on.

*

Where does this leave me, my ramblings and my empty bathroom cabinet.

Might atheism be a whole lot less trouble.

Any God I ever felt in church I brought in with me. I think all other folks did too. They come to church to share God, not find God.

Alice Walker

For my part I think God must exist in the space between one man and his relationship to the divine. To go into the corner of your room, hit your knees and begin your own communication. Any intention to evangelise or convince anyone of what you think seems fruitless, what they want to pursue or believe is their private business.

I looked for God, said Rumi. I went to the temple and could not find him. I went to the church and did not find him there. I went to the mosque, nor was he there. Finally, I peered into my heart, and there he was.

There was something else that came to me on the sofa as I had that Mufasa mushroom moment. The thought that God obscures himself for a reason, that this could be the crux of the whole thing. And those who so-choose go towards him, clumsily and perseveringly, like a shuffle to the loo half-asleep in an unfamiliar house. He has set this experiment into motion, wars and tragedy and natural disasters included, and that is the brief. To carry on Job-like, in spite of our suffering. To live the questions themselves, to act along the way in a manner that might bring one closer to some revelation.

The Big Man in the sky.

A monotheistic God, an unexplainable thing, an illusion perhaps, or not, who’s to say, one which every culture on earth – asides maybe from the present day one in the West – has developed a system of faith sounding in tune with their traditions and priorities. A man-made interpretation of the divine.

Religion is man’s way to God, and it is always erroneous.

Revelation is God’s way to man, and it is always perfect.

Still, people think they know, and no-one knows.

The ones who know, know they don’t perhaps.

Outside, in the courtyard, psithurism is in the house, the sound of the wind through the trees, that feels as Hesse said, like home, like a memory of the mother. It leads home.

Roger Scruton the philosopher, said something far better than any parting shot of mine. Sums it up in the shell of a nut.

Anybody who goes through life with an open mind and heart will encounter moments that are saturated with meaning, but whose meaning cannot be put into words. Those moments are precious to us. When they occur, it is as though, on the winding, ill-lit stairway of our life, we suddenly come across a window… through which we catch sight of another, brighter world – a world to which we belong but which we cannot enter. There are many who dismiss this world as an unscientific fiction. I am not alone in thinking it real and important.

*

Does He have a beard though?

No idea.

Might ask Him some day.