When I stopped working on the races I was glad, but it left an emptiness. By then I knew that everything good and bad left an emptiness when it stopped. But if it was bad, the emptiness filled up by itself. If it was good you could only fill it by finding something better.

Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

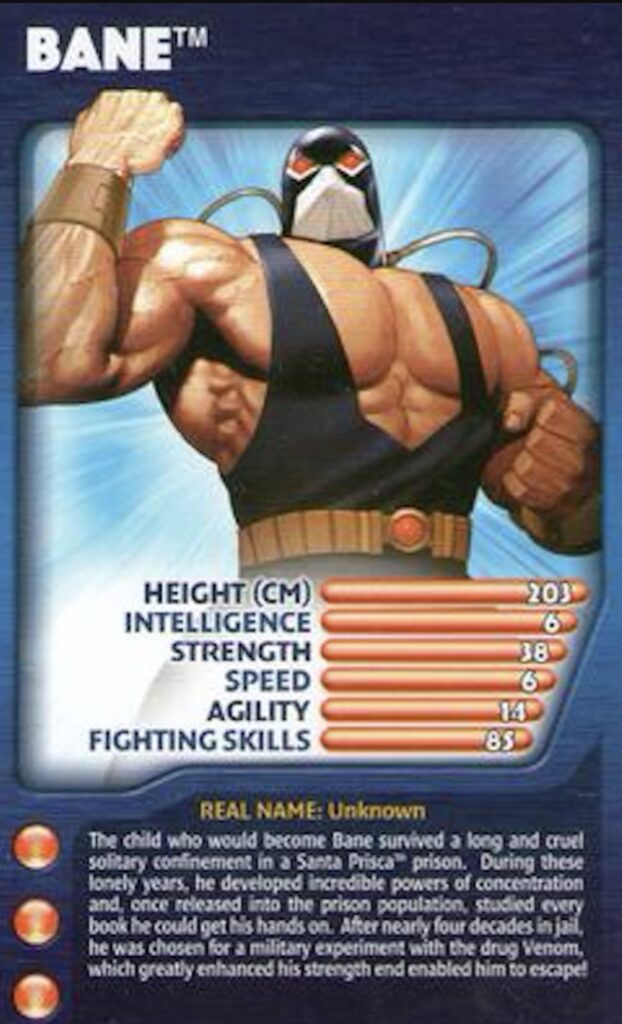

If he was a top-trump card, kids would whoop and holla when they got him because they knew the 98 score on power to chill on his jax trumped every other card in the pack. He’d lived out most of his young adult life with a corset on, the tightness of which symbolised the strength of his self-containment. Loneliness wasn’t for him. The company of other people, to give him what? His was a landmass surrounded by turquoise waters on all sides, well away from the maine.

On the off-chance he’d need to, he might seek company out. But always in a removed way that screamed out in veiled text that he wasn’t bothered either way. Even when his therapist flipped the script one day and told him his lonerdom was fear of engagement and his singledom was fear of rejection, he’d still beat the drum of one of the old Greek guys whose words echoed upstairs whenever he needed reminding. Self-sufficiency is the greatest virtue.

Seven weeks before he had given up drinking. And loneliness had crept up behind solitude and tapped it on the shoulder discreetly. My turn. And they had switched places. And now he felt lonely all the time. Perhaps not in the sense of needing to be with people. More in the sense of an awareness of the crushingness of how totally alone he was. Every single thought process which led to another thought process which led to another, was his alone. If he employed someone to a permanent position of listening to him speak his mind for twenty-four hours a day, an ocean would still remain present between them. Which led him to feel an ocean away from everyone.

Seeking help wasn’t really the issue. Since any help however well-worded wouldn’t penetrate. The issue had no core, nothing to get to the heart of. He could think of nothing more pathetic than wailing down the phone at somebody or staring deeply into a glass of sparkling water outside a café describing his symptoms and his ailments. And yet he had a sneaking suspicion he was doing his best to deny that he wanted more than anything for people to beat his door down and find him sat there in his flat at night, staring deeply into his glass of sparkling water, and ask him what was wrong. Nothing was wrong, he might reply. What is what.

There was a strange satisfaction in this death march. As if an unending set of enormous waves were crashing down on his head repeatedly, sending him spinning and tumbling into the depths, from which he’d surface just in time to catch sight of the next oncoming wave, to lock eyes and smile calmly at it. Then he’d go under again. It was calm and it was persistent.

A friend of his with a brain like a triple-decker bus and a heart like a champagne glass teetering on the edge of a table had told him that the colour would return. One day. The emptiness would fill up by itself. Or perhaps with something better.