Chapter 1

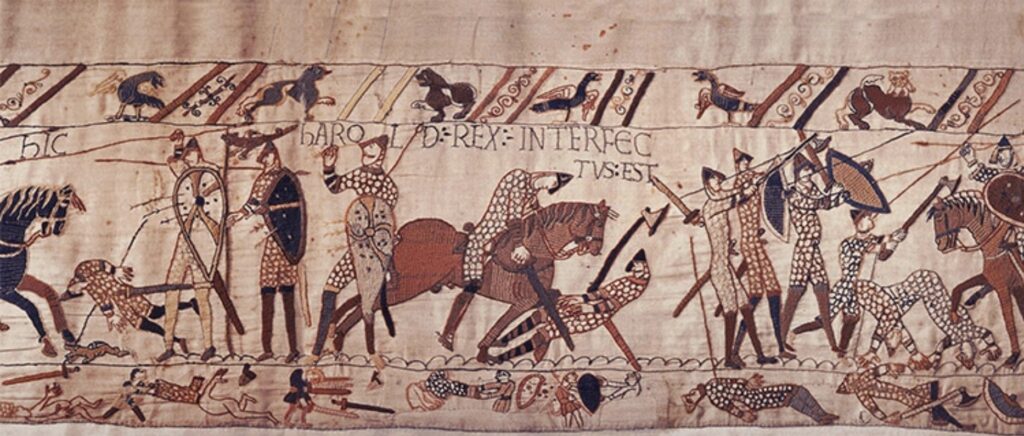

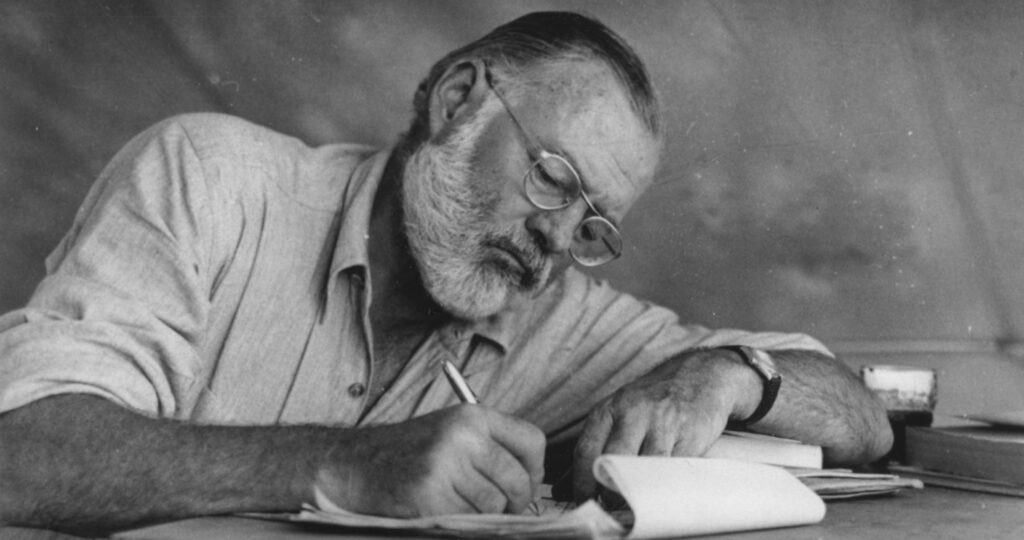

When my brother was born my father poured champagne all over him in the maternity ward. At the age of 63, Hemingway sat down on his porch in the early hours of the morning, poured out a glass of rum, and shot himself. ‘Holy Intoxication’ was encouraged in Ancient Egypt as an alternative state of being, a link to the world of the Gods. When Harold took an arrow to the eye in the corner of a field near Hastings in 1066, his first words were ‘bring me my wine’.

Humans like booze.

There’s that thing which says a drink is the tonic for all occasions. Happiness, misery, sunny days, rain, to celebrate a life coming into being, to mourn a life passing on. We drink to remember, we drink to forget, to commune with others, we toast our own company, we drink to feel different, we drink to prolong going back to feeling the same all over again.

I stopped drinking three months ago, and it has been such a weird trip that I have to write it down and try to give form to it because it has been one of the most confusing things I have ever done. When people are candid and throw their truth in your face without you asking, you stray in the murky territories of the #overshare. Unless you make it interesting, and then with luck it becomes characterised by its interest, rather than the fact someone is dumping the contents of their emotional hold-all over you whilst unloading it from the luggage compartment of your soul.

I decided to stop drinking because it had become repetitive. Not in the sense that I was doing it metronomically with no control over it, but in the sense that nothing new was coming from it. There was a gut instinct in me that I wasn’t doing enough to deserve it, while at the same time I found myself drinking in order to mute this voice in my head, drinking to bind the hand whose finger was gently prodding away at the root of this feeling of undeservedness.

On top of this, there was the added motivation that at weekends, one too many was leading me to do my best Toni Montana impression more often than I would like, which my sober-self concluded was fundamentally and categorically a waste of time, and I know enough to know a waste of time is the bedfellow of a wasted life.

There was also a feeling that time spent even not having that concrete an idea of what I was doing, was nonetheless time better spent than that filled doing something I understood was fundamentally bad for me. And things weren’t working out like that. Instead these two pastimes were playing a protracted game of musical chairs with each other, making an arrangement behind my back to sit down together on the one remaining chair in the room, linked in a warm embrace.

At the back end of another weekend, I made a decision and the shutters came down, and I stopped. I remember the subsequent first Friday afternoon, sitting there with my mate staring deeply into the hues of his pint, watching the condensation form on the outside of the glass. And then going home the following weekend to see my parents, telling them I wasn’t drinking. Any my father looking at me as if I’d just tied my shoelaces together, reminding me more than once at lunch how interesting the wine had become since it had begun to breathe, and how not to have a small glass with the main course was absurdo.

This thing is I agreed with him. I’m definitely on the side of the drinkers. When I go out for dinner with someone who announces they aren’t drinking there’s a voice in my head that immediately lets out an extended groan, and something in me lowers the bar for the potential of the evening. There is an unknown in a glass or two of something. And you sign up to that unknown once you take a first sip.

There is no unknown in a litre and a half of Highland Spring.

I count myself lucky i’m not one of those people who can’t ever have a drink of something again. In the knowledge that a big part of alcoholism lies in the denial of its existence, I can say with confidence I’m not there. For me this is an experiment that will at some point come to a close, and yet for the moment I can feel the presence of an unmoving 28-stone bouncer manning the door of my willpower that won’t let me reach for another drink again, until I understand exactly why I’m doing it. I have no idea what that understanding will be, but I know one hundred per cent that I’ll know.

I haven’t yet gone into why and how this whole process of sobriety became so confusing, but it was divided up into three specific stages, all as strange and delusional as each other.

Chapter 2

Last year I started writing an account of my decision to give up drinking. I described it as one of the most confusing things I’d ever done. The reason it left me so confused was because I didn’t learn anything from it. Well I kind of did and I kind of didn’t. But strangely the lessons I did learn seemed to vanish into the ether pretty quickly. The whole exercise had some point to it, whilst simultaneously proving in the end somehow pointless.

Having said this, it was one of the most important things I’ve done in recent memory. Me saying I didn’t learn anything springs from the fact the now, five months later, I’ve resumed a pattern of drinking none too dissimilar from the one I was in before I stopped. But the aim was never to stop drinking completely. The aim was to take a peek behind the curtain. And to mull over whatever it was that peek might reveal to me, over an ice-cold pint of pilsner.

To say I didn’t learn much isn’t true. We always learn. Even when we don’t, we somehow do. I’d say my experience could be split up into some key stages of being, appearing to me one after the other.

The first thing I felt was smug.

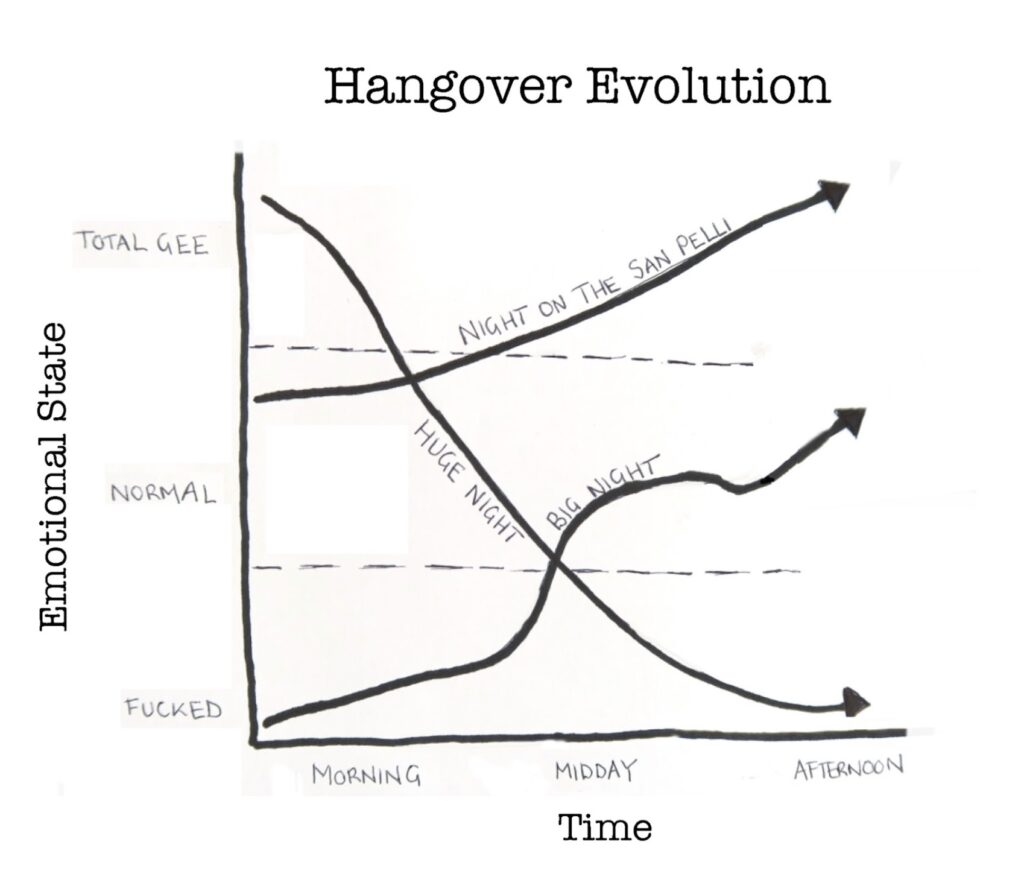

The most immediate and obvious effect of stopping drinking is clear.

With not a milligram of hangover, the magic of the wake-up lies in beginning the day on the right side of normal. From here a smooth transition into Total Geedom is by no means out of the question. Have a big night however and you don’t get out of normal until most probably late afternoon – the state in which you begin when you don’t drink. On a big night with the wrong type of hangover, you might not even by the day’s end reach the oasis from which your teetotal self has been calmly sipping all day.

Another option is to go nitro and have an absolute blinder. At least you wake up feeling marvellous, because you’re still drunk. But from then it’s a headlong freefall into the abyss. Which depending on how philosophical your mindset is, or more importantly how much work you have on, can be quite funny but more often than not an absolute living death.

In this new hungover-less state, the greatest difference I found from the off was that I woke up winning. I didn’t have any hazy memories of candle-lit heart to hearts or Campo Viejo-fuelled rants, but what I did have was no headache. The rocky road from fuzzy-headedness had had an upgrade, and now more resembled an Autobahn to world domination.

This mental clarity also served to dampen the voice of my self-doubt. With no hangover gnawing at me, everything had hope, everything had potential, things were worth trying. There was less fear, less non-engagement. The glass wasn’t just half-full, it was over-flowing with San Pellegrino.

The decision to stop drinking took on a force all of its own. As I said a 28-stone bouncer manning the door of my willpower had moved into permanent residency in my brain. The expression on his face of unflinching brutishness could be seen mirrored in my own, whenever the possibility of a drink presented itself. It was self-perpetuating. The greater I felt, the smugger I was, the more I wanted to sustain it, the less I wanted to drink.

I felt fucking great, and just as any state of prolonged smugness should rightly bring with it, I soon became unbearable. I’d see groups staggering out of pubs at 10pm on a Sunday and think how they were throwing their lives away. I’d see baskets in supermarkets loaded with tinnies and feel my eyes roll to the back of my perfectly sober head. My U-turn was shocking. I was turning into a sanctimonious dick.

And I was loving it.

But all good things must come to an end.

Towards the end of my fourth week sober, I friend of mine suggested a pub visit on a Thursday afternoon. My smugness had been gradually waning, the novelty of my new lifestyle was becoming no longer novel. I’d had a shitty day, and I wanted nothing more than a release. The kind of release not many things in the world can give you quite like the first few sips of an ice cold lager. I went up top, and there was my bouncer friend, looking especially lairy, gravely shaking his bald head. So I went to the pub and sat there monosyllabically for half an hour with a soda and lime. I got to the bottom of the glass, made my excuses, went home, and fell into a deep depression.

Chapter 3

It’s Wednesday today. I’m hungover.

Not a completely incapacitated hungover. I’m the level of hangover where I can take thoughts by the hand and toddle them to a conclusion, but my sight. If I don’t make a choice on what to focus on my vision doesn’t hang attentively in the middle-distance, it blurs into a soup of light and shadow. I’ve drunk so much water to flush out the alcohol that i need to relieve myself every twenty minutes, which is a drag. And still my mouth is dry like a desert at three in the afternoon. This has become an ordeal.

A pretty good state in which to finally conclude my trilogy on alcohol. I wrote the first part fifteen months ago, in the grips of sobriety. The second part this time last year, having jumped off the wagon at high speed, and now the denouement, one year on, sitting here staring out of the window at summer unrobing herself, sozzled, fed up, and in fervent need of unsozzling.

I don’t have a problem with alcohol.

Honestly.

*

To recap, there were specific stages I passed through in the aftermath of giving up drinking. First came the unbearable smugness of waking up on the right side of the bed, not just on the odd morning, but permanently, without a trace of hangover. Of seeing people in supermarket aisles with shopping baskets laden with tinnies, and shaking my head disdainfully as I watched them throwing their lives away. Of turning into a sanctimonious dick. Of increased productivity levels, increased self confidence, of glass half-fullness. I was the me I wanted to be.

But the thing is, it didn’t continue. After four weeks the novelty wore off. The mist cleared, and the abyss that had been there in front of me all along revealed itself. And I realised why we drink. I think we drink to not feel alone. Over night, my self-satisfaction had morphed into something very sinister. As if loneliness had crept up behind solitude and tapped him in the shoulder discreetly. My turn. And they had switched places. It still felt like me against the world, but my outlook was no longer one of defiance, as it had been when I was basking in the glow of my own righteousness sipping San Pellegrino. It was one of fear.

I was alone.

It wasn’t that I needed to be with people, it was more in the sense of an awareness of the crushingness of how totally alone I was. Every single thought process which led to another thought process which led to another, was mine alone. If I had employed someone to a permanent position of listening to me speak my mind for twenty-four hours a day, an ocean would still have remained present between us. Which led me to feel an ocean away from everyone.

The wool had been pulled back from my eyes, and I saw what was actually going on. Without the drink, the distraction, the mood-altering elixir, I was forced to sit there with my demons. Instead of reaching for a pint whenever things got heavy, I had to welcome in my darkest thoughts and sit in them. I had to meet and greet the worst parts of myself and befriend them. Just a little something to take the edge off please. But I didn’t have access to that. And I learnt that a lime cordial doesn’t take the edge off. At all.

That first plunge into a cold, crisp, obscure craft beer, medium-hopped, easy-drinking, the one with that cool lick of condensation running down the outside of the glass, invaded my dreams.

I read somewhere that we ask ourselves the wrong questions. The question is not why do we drink. The question is why aren’t we all lying on street corners drowning ourselves in booze around the fucking clock. The question is not why do we get anxious. The question is why aren’t people terrified out of their skulls every second of every day to the point where they can’t even move. Anxiety isn’t a mystery. The mystery is how we ever achieve brief spells of calm. The point of drinking is to relieve us momentarily from the unbearable suffering of being alive.

And so the second month of my sobriety was characterised by a month-long depression. I had broken the shell, and I stared out across the cinders of the world with naked eyes. I went up to 8 espressos a day, my San Pellegrino intake quadrupled, and I went into isolation. I no longer looked down on drunks, I envied them. They had taken what I so coveted, and I was jealous. Swilling their cheap malbec and baring their sediment-stained teeth, they laughed at me.

*

My mate Tom said that when he stopped boozing, he didn’t miss the drinking so much. What he missed was the binge–drinking. He missed the oblivion. Some people need an escape from their brain much more than others. In his brilliant autobiography The Story Of The Streets, Mike Skinner, no stranger to self-destruction, said the following:

That’s why I insist that my psychic deterioration was down to a lack of drink and drugs, rather than anything else. As bad as those things might be for your longterm health, they’re still down-time. Which someone who gets as caught up in his own head as I do, desperately needs.

I had drawn back the curtain, and I was encountering exactly what it was to be caught up in my own head, all the time. I had eliminated the most obvious, in your face, socially acceptable, by far and away most entertaining way of achieving down-time, and in its absence I was left pacing the floor of a room without an exit, and the inescapable, slowly creeping feeling that…

This is all there is.

Once I’d processed this, I came out of my depression. And my hangover from it, was this fundamental understanding of how alone we all are. Totally and completely alone inside the prison of our own minds, going over and over and over the same thought processes, the same ways of seeing the world, the same anxiety and paranoia and the same fear of never being enough. Small wonder we need a fucking drink now and again. These are mood-altering substances for a species in desperate need of having their moods altered.

I lasted another couple of months, with less and less enthusiasm, and one Friday I went for dinner with a friend in Soho, sat through a litre of Highland Spring, something in me broke, I screamed:

E N O U G H O F T H I S M I S E R Y

and went and got annihilated. I’ve never looked back.

I said before that the whole experience of giving up drinking was one of the most confusing things I’ve ever done. The reason it left me so confused was because I didn’t learn anything from it. Well I kind of did and kind of didn’t. But strangely enough the lessons I did learn seemed to vanish into the ether pretty quickly. The whole exercise has some point to it, whilst simultaneously proving in the end somehow pointless. Like a joke that you get, but just don’t find funny.

I have a feeling it belongs in the company of those lessons we have to learn over and over again a number of times in our lives, because we’ll keep forgetting them. The clarity that sobriety bought me was terrifying, I preferred the murky lie. I still do. The truly insidious thing about alcohol is that it is blinding. It blinds us to the truths waiting there for us to stare them square in the face, but don’t have the courage to.

Mental discomfort is an alarm bell signalling we’re getting closer to the stuff that truly needs our attention. As someone once wrote, the alcohol is not our friend, all it does is persuade us our awful jobs and dreary lives are fine because who needs to challenge the status quo when we can just shuffle down to the local instead.

*

I never thought sobriety would be so difficult. I never thought I’d have to get so lost to find myself. And then realise I preferred being lost. I never thought I’d have to start drinking again to save myself from being sober. And more than anything, that alcohol has very little to do with any of it in the first place.

The tough thing about booze is that it’s the angel and the devil. The beautiful and the lethal in equal measure. And life without it is a bore. Of course, there is such a thing as drinking for pleasure. There is such a thing as moderation. But those who don’t admit that line is a blurry one are probably the ones who need the most help. Or just another drink.

In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway wrote:

When I stopped working on the races I was glad, but it left an emptiness. By then I knew that everything good and bad left an emptiness when it stopped. But if it was bad the emptiness filled up by itself. If it was good, you could only fill it by finding something better.

*

You could only fill it by finding something better.

That’s about it really.