When I am old and beaten down by my years I will raise a smile and remember the time my uncle took me to discover beer. For five days we had walked the entrails of the Swiss Alps and now, at the end of the last and most difficult day, outside a mountain hut in the shadow of the Matterhorn he announced it was about time for a drink.

The glass was set down before me and as I peered into the golden squall with eyes narrowed and watched the waterfall of tiny bubbles rising up towards the head, I was afraid. After all this was beer, and I was eleven. Never before in my life had a beer been intended solely for me.

Inured to the mountains around me I zeroed in on the glass and raised it to my lips. The liquid washed over my tongue and into my gullet and somewhere in the bowels of an undiscovered darkness a flame was lit. I took down my first ever beer in two gulps.

Later, in the lengthening shadows of my teenage years my mother would frown and shake her head as I approached the breakfast table blurry-eyed and puffy-faced from the previous night’s excesses. We come from a long line of professional alcoholics, she barked, you better bloody watch out.

I knew back then what I know now, that her fears were misguided. Because for me it was only about the moment. In the mists of an eight pint marathon, in the pause between the second and third sip of the opening drink, the moment would reveal itself. A coming together of man and beer and time immemorial. An inchoate idea of the pointless repetition of everything and the beauty of this and on account of it, a deep contentment to be alive

*

1942, an old man is sat in the hilltop village of Tricesimo having a moment. Another man approaches him with a proposal, to which he consents. Che al mi dedi di bevi, mi baste he says in old Friulian dialect. ‘Enough to drink is all the payment I need’. The man with the proposal is the owner of a brewery, the old man becomes the face of Moretti the renowned Italian beer, and the moment is fixed forever in time.

As I moved into my twenties the pint-swilling of youth died down and the quality of what I drank began to exceed the quantity. Maybe it was an understanding that the moment came fairly early on and then vanished, and that any pint past number four added no value and was an unhelpful amount of liquid to have in your system.

For six months I lived in Paris and there I learnt restraint and class. To Parisians a drink was more a footnote than the be-all of an evening, I saw how it was possible to sit with an empty glass and not have a panic attack, I found out first hand how the skulling of une pinte in ten minutes was roundly considered une folie.

But our local supermarket was well-stocked and in the aisle one evening I came face to face with the Trappist beers of Belgium. Leffe, Chimay, Grimbergen, these names produce a reverie in me like birdsong and the smell of freshly fallen rain.

I would sample a new one each week, gradually adapting my taste buds to the more nuanced flavour. And then one day came the revelation of beer and nuts together, a watershed moment that arrived like the fulfilment of some destiny. Jean-Claude Van Damme’s ‘mouvement perpétuel’.

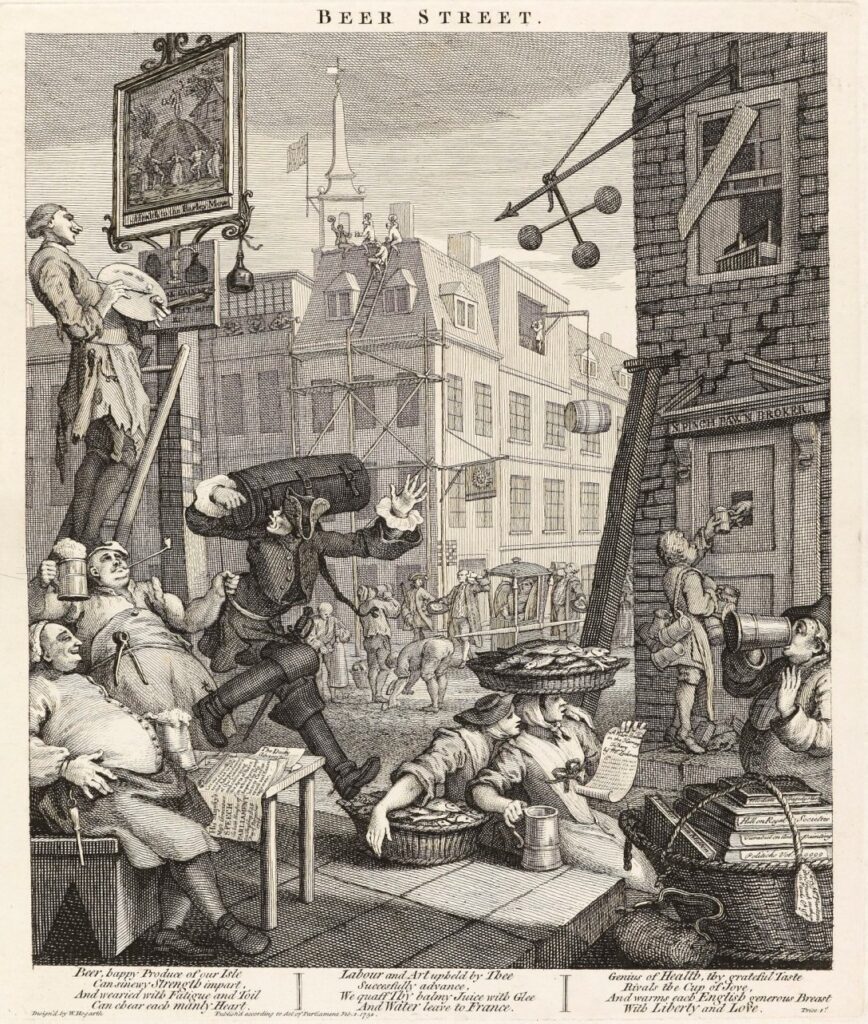

The Sumerians started the party in 4000BC. The Cistercian monks carried the torch through the Middle Ages. In 1751 Hogarth drew ‘Beer Street’. A century later Hardy described an ale ‘full in body, yet brisk as a volcano; piquant, yet without a twang, luminous as an autumn sunset’. And at last in 2011, came a whisper on the wind, a spark to the flame of the bonfire.

Every drinker through the ages must have thought they were sampling the sublimity of beer. They were wrong. For just under a decade ago, the giant leap for mankind was taken. The honeyed hops, the fizz that crackled, the hazy condensation on the side of the glass like dew on a spring morning, the craft beer had arrived.

The pissy beers of the noughties receded into the distance and made way for the new kids. Carling, Becks and Numbers became Brewdog, Beavertown, and Sierra Nevada. The format got a makeover. The 440ml can was jettisoned in favour of 330ml, a nugget of ice-cold wizardry that fit in the palm of your hand like a daydream.

The crafty was born.

And so was my alcoholism. In my teens I envisioned being the guy who had beers chilling in his fridge at all times. But for a man obsessed with finding the moment, the invention of the crafty threw up some problems. The crack of the can, the feeling as it touched my lips, I realised I could have my moment at home, whenever I desired.

I threw out my greens and cranked the fridge to optimum beer-chilling temperature. And an idea sidled up to me silently; it was always the right time for a crafty. To celebrate, to mourn, when I was pumped, when I was blue, when things were going great, when I wanted things to go better. Was I out of control, I couldn’t tell.

I still can’t really.

A Lithuanian builder Rom, a man of deep winters and cheap vodka, taught me once the key to a hangover was a beer as soon as you woke up. Just one, no more than that. And I tried it a few times, and it worked. But it also struck me as a dangerous place to dwell. Like there was something sinister in it.

Maybe my mother was right, perhaps I should’ve been wary of alcohol. At some point for sure it stopped being an adventure, and became a place I recognised, like getting in an elevator and knowing which number to press. And the dawning realisation that if something terrible were to happen to me, I don’t know if I might not consider it a refuge.

But I’d tell you my weakness wasn’t for the alcohol. It was for the crafty. That 330ml nugget. The moment. If the can wasn’t chilled to perfection I wasn’t touching it. Hand me a normal beer and I might hand it back to you. If an off-license was fresh out of crafties I wasn’t about to pick up a few Coronas, I was leaving empty-handed. There was a method in the mania.

The world isn’t an unlikely place to want to escape from. And there is an unknown in a drink, an oxygen, a door that opens to a new room. Every time I cracked a cold one I stepped into that unknown. I tried giving it up once, but it was a lesson hard-learned.

I’ve watched the old men in France congregate in village bars at 9am for a demi. In an East End boozer one afternoon I saw six men deep in conversation, each with a drink, each sitting at their own table, shouting across the room at each other.

My uncle Carlos would wait for his family to leave the Estancia and then he would go and sit on the terrace looking out over the Pampa with a drink, and would toast their departure. He told my old man it was his favourite pastime.

*

So here we are.

A man walks into a pub and approaches the bar. It isn’t yet busy but has the feeling of a room warming up. He clocks the barlady and motions to one of the taps and smiles. She tilts the glass and flicks the tap and the hazy liquid washes down into it, he turns and with his back to the bar looks out across the room.

The night ahead promises all the excitement of the unknown, but he knows this is it. The mountain top. This is the solo-sharpener, the peace before the maelstrom, when there is no need to talk, only to stand there in some idle thought, in the moment.

One man and his beer. He takes the pint in his hand and lifts it, then lifts it further, making a motion with the glass through the air, in a toast, to someone or something only he knows. Then he drinks.