Overlooking a lagoon rising out of a desert of grass there is a little hill. On it sits a house. The womb of a family. I went there in August on my own. Touched base with a part of me I’d been ignoring, that had been gnawing on my insides for years. They say the happiest people in the world are those who have been released from some sort of shackle. That’s me. Thumping my chest like a bass drum.

Not scared anymore.

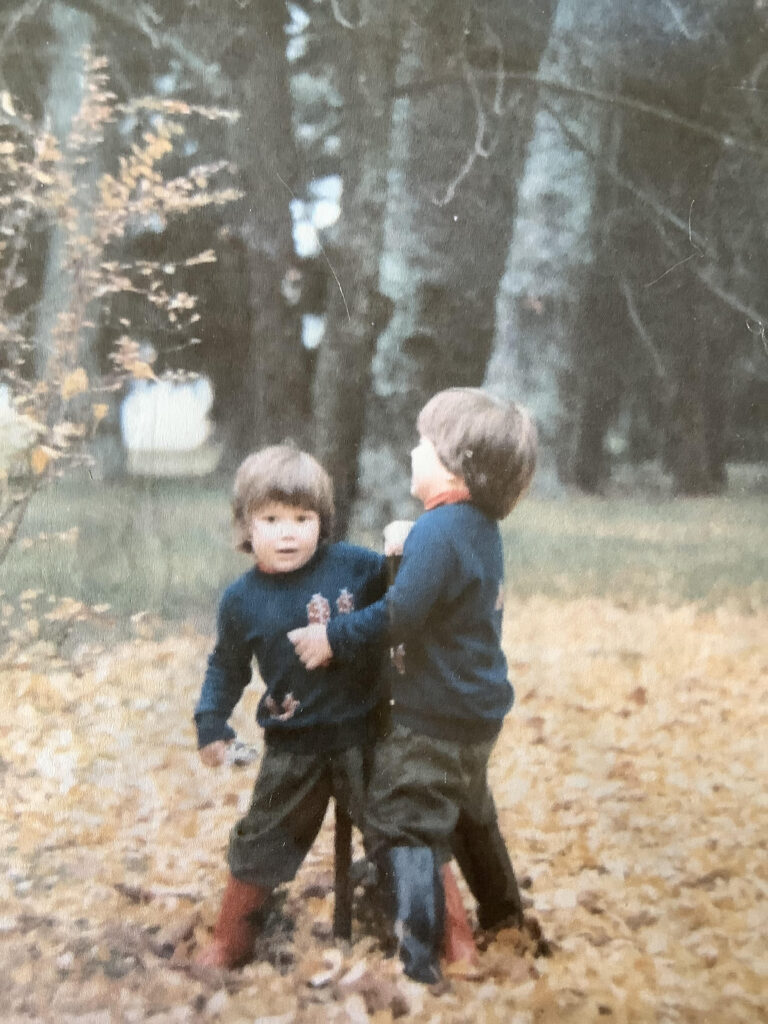

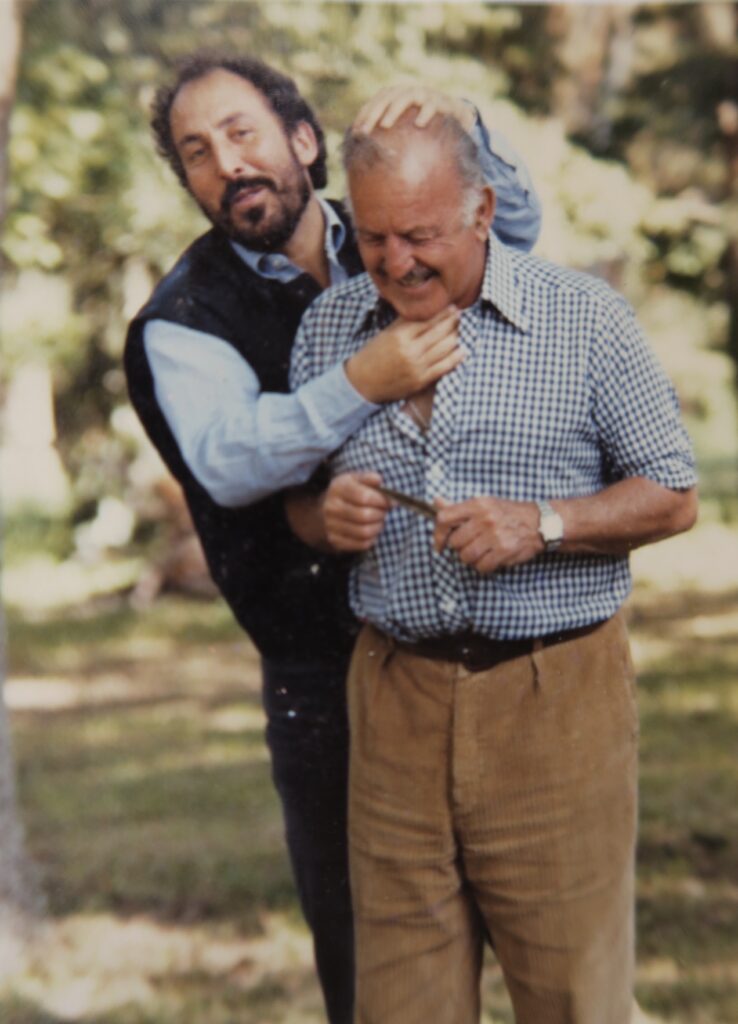

My father came to England at the start of the 70s, to escape a tired Peronismo but more his parents, worked in Gospel Oak as a psychoanalyst. Ten years later at a cocktail party he met my mother, proposed five times in 3 months. Two years later my bro appeared, and then me. Being called Domingo was definitely uncool until well into my 20s. I drew the long straw. My brother’s full name is Miguel Martín Tomás de Teresa de Jesús Cullen. An exile in a foreign land, no 7,000 mile stretch of water was going to stop my father, hellbent on making his children as Argentine as possible.

Every school holiday saw the four of us on a plane, my mother writing Spanish vocabulary furiously in pocket books, learning the language from scratch aged 39. In the beating English summer we spent two months out in the Pampa, jumping in puddles, huddled around fires, watching the winter course through the plains and beat against the wall of our fortress, the great trees that held us firm.

We grew up mestizo.

In a strange no man’s land. English but not quite. Not Argentine but nearly. Months of horse riding and campfires, mud and bruises, Nesquick and boredom and the endless horizon of the huge expanse waiting there like a sea. The birdsong. The electric storms. The runaway horses. The power cuts and candlelight.

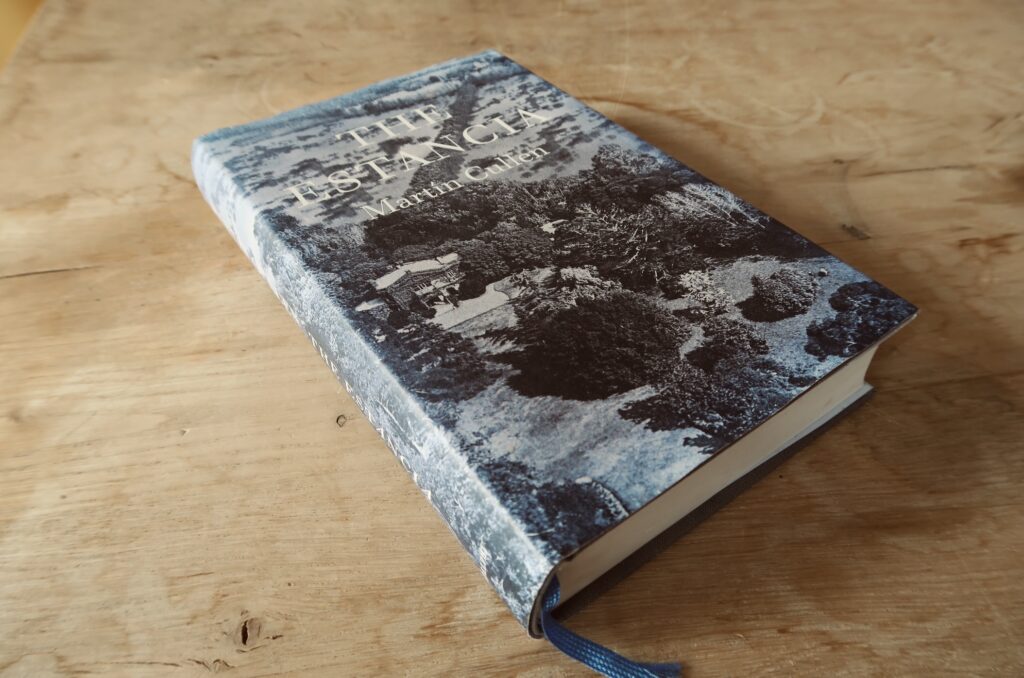

You could write a book about it.

My father did.

Took him forty years.

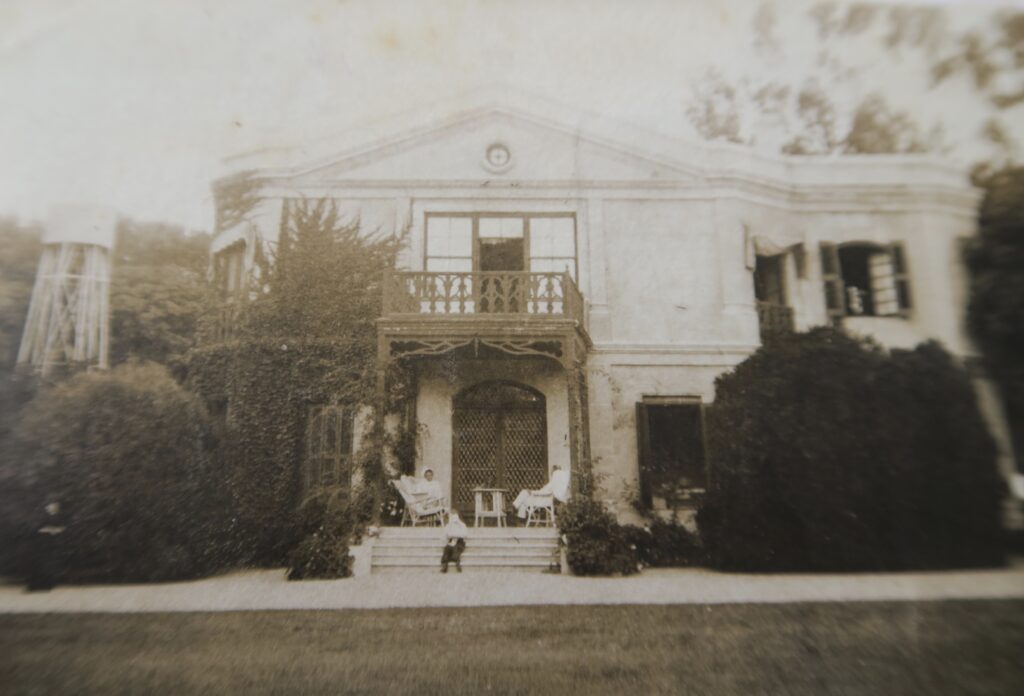

The Estancia is the house on top of the hill. Santa Helena was built in 1881. One of the many estancias divided up in the hectares our ancestor negotiated from the indigenous Indios who reigned over that enormous territory. When he died mad and scribbling on walls after years of government house arrest, the Indians stole his body and took it back with them to the pampa.

For seven generations it has been the home of our family. The trees, the birds, the laguna, the stink of sweat and horsehair under the cincha of the recado, my whole Argentine family grew up here.

‘We were woken by the sound of the gravel being raked, and then, when our nanny Gilda opened the window, by the white glow of the maple tree. The sun, already strong, reflected the white of the gravel and the white of the tree, and gave our unassuming country morning the radiance of the sea, or snow.’

The Estancia, p.127

My father, his brother, and his sister fought over the division of the house. For a decade. It was the source of so much angustia. Recriminations, lawsuits, resentment. Feeling they had a right to what was theirs. Feeling what was theirs being taken from them. It drove a stake between them. In the Latin way, unfamiliar to my English side, of loving and hating simultaneously, best of friends and enemies. In the end my father and my tío Carlos flipped a coin for the house. It has its own name now, its own folklore. La moneda, they call it. Papa won. The land was divided three ways.

The house, up on the hill, kept watch, over this family. Through seasons, her colour morphed from green to maroon to stark grey, on moody days the wind moving through the eucalyptus drowned the call of the wood pigeon and the chimango and at her edges the endless pampa bayed to come and subsume all to its will. In the evening my father liked to walk to the palos at the end of the park, the border between us and that plain where the shore meets the sea.

‘The vast landscape was deaf to the beating of my heart, and still it urged me to follow, to disappear within it. What do they know, those who speak of stillness? I stood there with the flat vista stretching out before me, the locked door of the casco at my back, and behind it the sunset burned, its light spreading out in a semi-circular fan before me. As the horizon receded, the smells of the pampa, revived as the heat exhausted itself, returned; mint, grass, dung, the dust of the corrals. But my trapped eyes ignored them. There was no smell, no temperature, no sound, only the silent fire at my back that enlarged that empty world that was me.’

The Estancia, p.158

Jaded by the fights, Papa left the house to me.

You’ll be better at fighting off the people who want to take it from you, he said. It doesn’t make sense to Miguel and I. The house is ours. When I think about it, the house is not anyone’s. Our family is the house’s. Santa Helena owns all of us. She has done for 140 years. All of us, generations of our family that have slept in her womb, walked her corridors, treaded her steps, flushed her cisterns, even the families of sirvientes and peones, park keepers and mayordomos. She owns all of us.

*

Analia brings me breakfast in the comedor, the steam from the coffee rises up in the air of the morning, the fires crackle in each room. I am alone in Santa Helena. These fires lit for me? I write to pops, hellbent on hearing my news. He’s living your every breath, my mother says, but he doesn’t want to bother you.

No se quiere meter.

I sleep in my mother’s bedroom, watch the embers spit in the darkness I shift position and hear the brass bed jingle, the linen sheets my old man loves are scratchy. I am happy alone in this big house listening to it stretch and sigh beneath me. The next morning in the bath, I look out at the window towards the laguna and remember being small, sitting at night as the water grew cold watching the frogs on the outsides of the window still as old stones lying in wait for bugs, and their tongues. Slop. Gobble. Gulp. Heavy weight of memory.

I read a passage in the book, feel something fathoms deep move in me.

*

So that was me.

Locked for years in this scary bind with that land I somehow didn’t feel worthy of.

I had cousins aunts uncles grandparents, memories, and I felt scared. When people came back from BA and declared it the coolest place on the planet I would grin and bear it. I wasn’t a tourist. I wasn’t a porteño. I didn’t know where to fit. I felt not Argentine enough. I remember talking castellano to someone on the flight back once and she commented that my accent was strange and it killed me.

The car ride from Ezeiza to the centre of BA was blind fear. I wanted to hide. I still feel it. Round at dinner at Solís, Vivian a friend of our family, did the maths. Of course you felt fear. Think about how tense tu papa must’ve been. His relationship with papapa and mamama was so strained. I saw it all the time. You could cut the tension with a knife. He would’ve been a state, your mother would’ve been a state on his account. Imagine you two, hiding in the backseat, feeling all that. Like heading into some sort of purgatory.

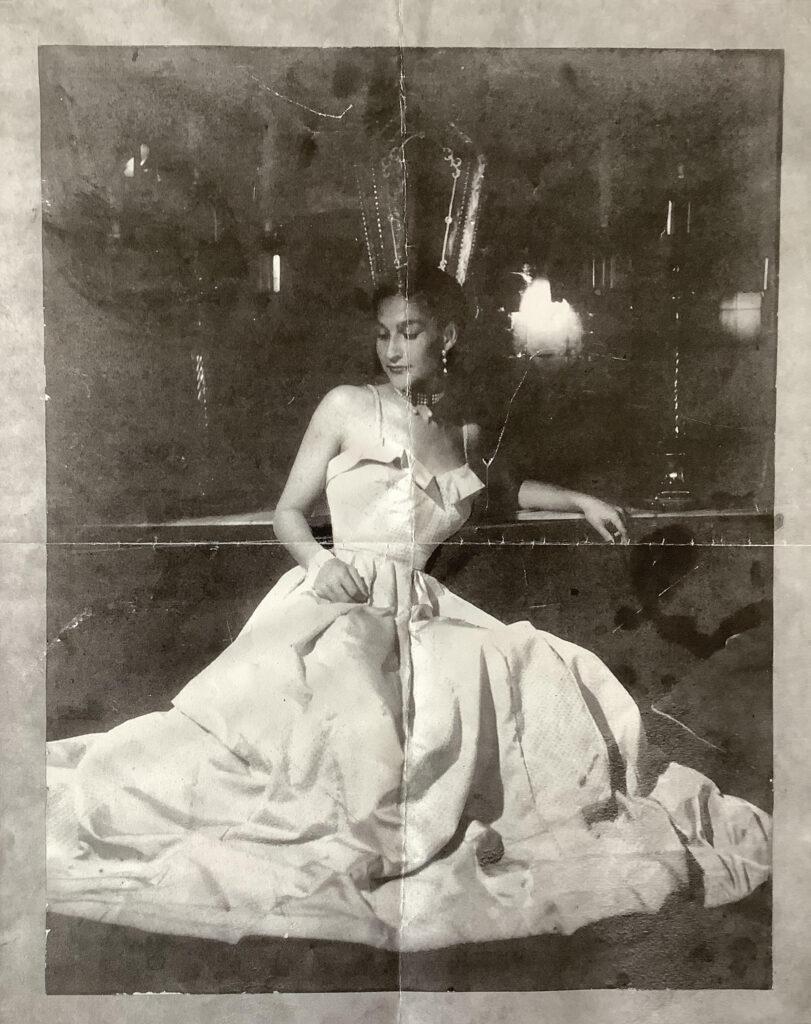

Alone in BA I walk the long corridors of Esmeralda and hear the wood creak underfoot and think of them all. The ghosts still there in that huge empty apartment. Mercedes my aunt said it terrified her to sleep there alone. But I don’t feel afraid. If mamama walked in to talk to me I would love it. Through the open door is the room where her and papapa died.

Every room full of the past.

When I was 28, one winter’s morning papa and I went rowing on the laguna. It was windy, twice we rescued his panama from the water. Half way to the gallinero, I broke down. Que pasa! he said. I can’t do this. Do what. I can’t do it all, I said in tears. I can’t teach Ruben about trees. I can’t talk to Analia about flowers and oeuf cocotte and borders, I can’t be their shrink and their confidant, I can’t give them orders, I can’t teach them about history, I can’t tell them what branches to prune, I can’t carve lakes out of the earth, I can’t make decisions about cows, I can’t earn their respect, their fear, their love.

I don’t know how.

Whatever you’re crying about, whatever you think it is, it’s not that, he said. It’s something else. Francamente, he said half-laughing.

Back in Blighty, scared as I was, I confronted none of it, and my relationship with that earth, that house, fell into shadow. It gnawed at me every day. The source of my biggest fear. An enormous black presence I chose to avert my gaze from. Papa would get sad, why do you not go there. I thought to tell him, but it was so hard. It felt like my failing. I didn’t tell anyone anything much back then.

He must have thought I didn’t care.

Why don’t you ever invite us out, my friends would clamour. I told myself it was another world, they wouldn’t get it. Now I realise it’s because I knew they would sense my weakness. It sounds silly and yet it had wormed its way inside me, it was fixed there like a simple pin. I didn’t even question it.

Matt went out there with Miguel once, we went for dinner on his return. What are you doing, he cried. Go you idiot. You have such a beautiful family out there, waiting for you. All they want to do is see you.

*

In February this year I awoke with the mother of all hangovers. Went to get a coffee and my card got declined. It came flooding back. Fuck. Alfie and I had got loose, extremely loose, gone deep about Argentina for hours. Your fear is your guide was our motto. We were shouting it by the end. Not before I’d booked a one way ticket to Argentina, club class, leaving in three days. I rang up BA, got a refund, and fell into a six week depression.

But somewhere on a rusted track wheels had clanked into motion.

After a post-covid summer of love, I booked a ticket. Followed my gut. I don’t quite know why, something inside told me I couldn’t not. My uncle was ill. The end of winter was approaching. Days of cold sun slowly lengthening, the sea of grass, fires lit, the birds. I made my way across the ocean.

I spent three weeks there. Three weeks of something exploding in slow motion, something freeing itself. With my cousin Francisco we went to Santa Helena. He left, I sat in the comedor alone. On the terrace. To Kakel with Fede, riding back, the smells of tierra and junco, the horse’s sweat under the recado, five years it’s been and feels like yesterday, I say to him. Literally, I did this yesterday. With Ivan to the far flung territories. Without papa I felt an envoy, in some small way like a patroncito. That I could fill this hole after all.

There is part of my old man that is so consumed by that place he can’t give it up. Mi casa, he calls it. And then when he’s tired and bored of the endless task of it all, he says I’m doing this all for you. Tu casa. You don’t have to be your dad! Mariano our administrator cried out in the comedor one evening. You do it your way. You have to be you.

When I was sad and anxious I thought I must clean my hands of it, I can’t bear for it to be there, the whole weight of this family, the responsibility of it all on me, thousands of miles away drinking craft beer in Hackney, that house, the womb that carries us all, lying empty. The fear would take me. The same fear I now had to go towards. As I felt the spirit of my grandmother accompany me to the loo I thought what madness. What am I even thinking. What would she think.

Back to the bath.

Sitting there looking out at the windows recalling the frogs. Reading what papa had written 50 years before. I realised I was the last, not the last, the latest link in the chain. And I had no right to break it, because if I did it would shatter into a million pieces, who knew what else might break with it. Like Muir said, tug on anything at all and you take the entire universe with you.

‘We stretch like those tiny frogs that stick to the glass of windows at night in the estancia; and when immobile resemble straw coloured moths, but wet and translucent, craving rain with protuberant eyes and trembling throats, taking aim at the insect dazzled by the light of the room we are watching from, the diminutive frogs let loose another long and avid tongue to swallow the insect with a shaking of its whole body. But they are still hungry. Because they never tire of being hungry.’

La Estancia, p. 396

In all endings are my beginnings, all time is eternally present. The same frogs stuck to the windows of our past. Of my father’s. The same ones mamama would’ve seen, and otramama before her. We move our fingers back along the chain, feeling it like Braille, like the rosary. Link after link after link.

*

I went rowing with Fede as the sun was falling.

A funny thing not feeling afraid. You don’t feel it leave, you just notice it isn’t there anymore. As if like dust it has evanesced onto the wind. Rising into the enormous sky, carried on the streams that keep the storks floating like suspended stars.

We shall not cease from exploration, said Eliot, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started, and know that place for the first time. I think I understand it now.

You change. And the world around you changes. You reshape it, remould it, banishing the ghosts of the past, and see it as it is, untangled from the weight of old memory. The memory is there still, but lighter. And you pile new memory on top. The happiest people in the world are those who have been released from some sort of shackle. Always in a state of becoming.

I can’t be who I’m not. I must be who I am.

Around us the world whizzes on.