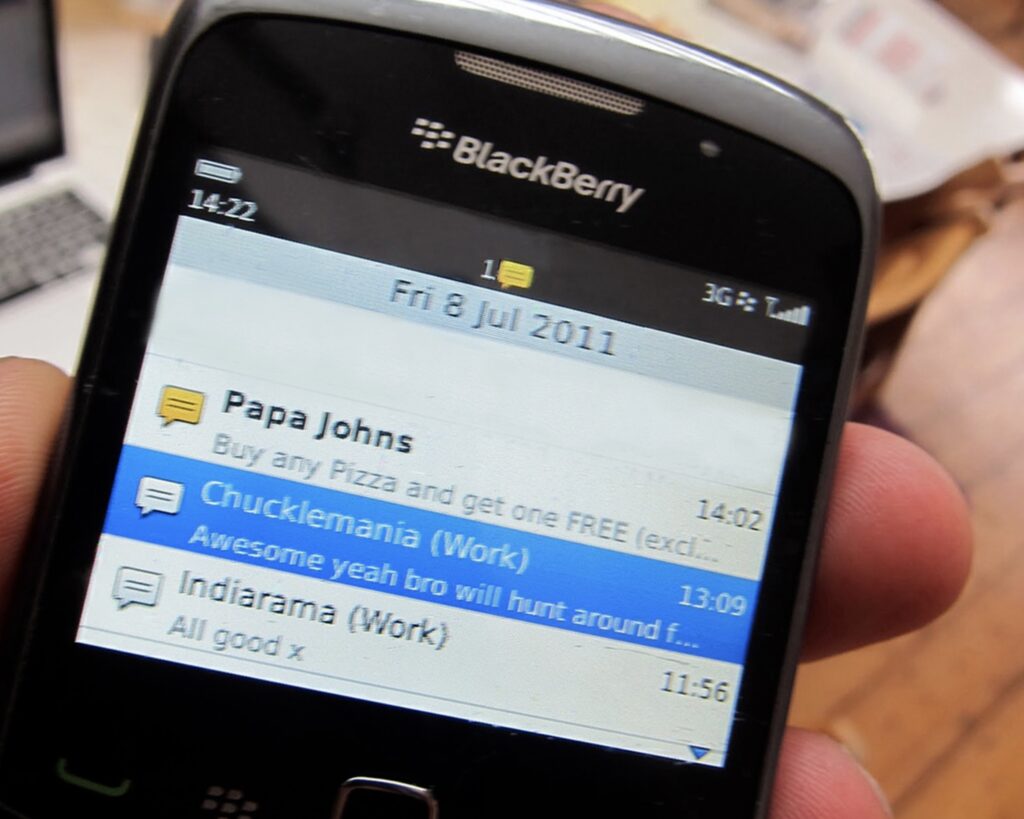

The last email I ever read on a phone was from Papa John’s Pizza in July 2011.

It was the middle of a long hot summer and as I gazed into the sad space between me and my loneliness a beep from my Blackberry Bold 9700 pierced the haze of the afternoon and warned me of a 2 for 1 deal I shouldn’t miss. Soon after I lost the phone and downgraded to a Nokia. That last call for pepperoni proved to be the last breath of my relationship with the internet in my pocket.

In the intervening eight years since Papa John’s came knocking I’ve hopped from rubbish phone to rubbish phone, and in the same timespan technology has become so advanced it is indistinguishable from magic. My Nokia 301 can do very little other than take calls and get texts, and the day I tried to download WhatsApp it froze and threatened to ignite.

These are the phones immortalised by the Matrix, that gave 90s teens their first taste of freedom from behind bedroom doors, the burners used by dealers to keep the police off their tail, and the reason Snake became the best mobile game of all time. These are the phones I’ve carried in my pocket for the last decade.

And I ask myself why.

And it’s confusing because I can’t give a straight answer.

Why, when modern life is increasingly run on them did I refuse to get a smartphone. Going against the grain had something to do with it, I suppose following trends did the opposite of what I desired, which was to be noticed. But there was one thing that bugged me. The lack of thought that went into the idea that the most recent thing must be the best. As if everyone was running blindly after what they stood to gain, and paying no attention to what they might lose.

For me, there are dangers in things being too good.

When I was a child MTV was too good, I would sit for hours flicking through music channels like a maniac until my parents banned me from tv. YouTube became too good, last month the Guardian published my account of a daily battle with a spiralling YouTube habit. If I ever go on a smartphone, the level of sorcery I feel like I’m wielding puts fear into me. So my technophobia has another root. Maybe I was policing myself all along, fearing the smartphone-shaped prison cell I might one day wake up in.

But there was something else. An emotion that would build up inside me when I spent too long on a phone, something tugging at my insides when I looked for too long at a screen. Too much cortisol, the opposite of peace. I hated it, and because I hated it I wanted to turn my back on it.

So for better or worse I spent the last eight years navigating my way through the modern world with a hunk of plastic that, dropped into a pint, would affect my life in no way whatsoever. The small print of which I’ve become so accustomed to it’s only when I write it down that it strikes me as strange.

*

I haven’t checked an email in the street since 2011. Or in fact anything apart from a text. I’ve never been on a WhatsApp group. I’ve never been on a Tinder date. I can’t use emojis. I can’t order an Uber. I can’t listen to Spotify. I can’t use Instagram. I have an iPod shuffle, a camera, a Barclays pin-sentry, and an unnecessarily heavy backpack. If I can’t memorise where I’m going I take an A to Z with me. I text friends to google things for me and the nicer ones reply. I still call 118 118.

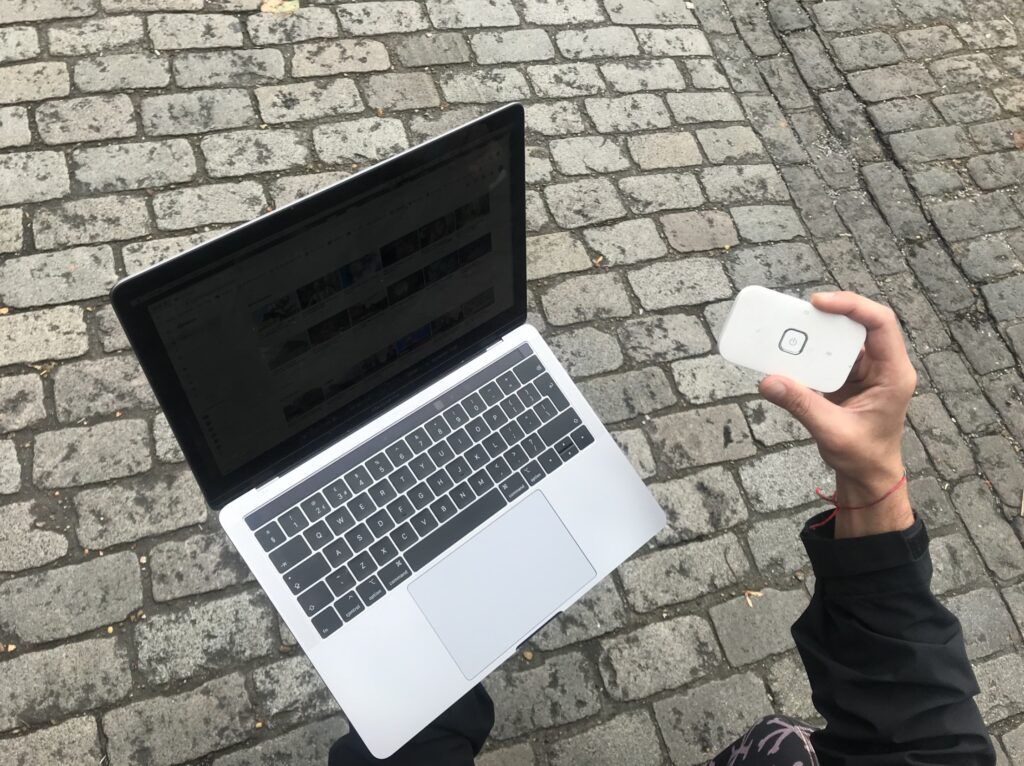

If I’m really screwed I can do this, but any info at all is the work of five minutes.

*

Four years ago in a restaurant, my parents began to frown.

It was the vision of a couple sitting opposite one another making no conversation at all, bent-double over their phones. What are they doing, asked my mother. I thought about how to reply. The thing is, I said… these things now mean you’re in fifteen conversations with fifteen different people, all at the same time, none of whom are in the room, all of whom need your attention. When do they ever get to be still, she asked. And we looked around, and half the tables in the room appeared to be under the same spell.

*

Much of this is about freedom.

Because a Nokia 301 really removes some options. I have no world in my pocket. No newsreel of other lives at the touch of a button. The only world I have is the world in front of my face. I can’t share an experience with anyone except who I’m with. I can’t get fomo because I have no idea what I’m missing out on. If I haven’t seen someone for four months I have no idea what they’ve been up to. My phone just isn’t very interesting. All I have is the living breathing world in front of my face.

And there is a deeper unconscious effect.

Because I have nothing to distract me from emotional pain I am forced to sit in my emotions and grapple with them. To bear the brunt of the pain and meet it full in the face and try to understand my worries, rather than suffer the anxieties they create. And in the end, perhaps this has obliged me to get to know myself better. Few people can have described this better than Louis C K talking about why he’ll never buy his kids a phone.

A year and a half ago I walked into a pub on a cold December night and saw a girl across the room waiting tables. I peered deeply inside myself and summoning up the courage, I walked over to her and asked for her number. I’d been single for a long time, I had no leads whatsoever, I was running out of options. And she was… well. I don’t think I would have met my girlfriend if I’d had a smartphone. I would have been too distracted by the world inside my pocket to notice her.

The real things, the truly important eternal things, don’t exist in pixels. They exist in front of our faces. The real world of real happiness and real pain and smells and laughter and the spaces in between, where the beautiful depths of life reside.

But in search of them we huddle around our devices, warming ourselves by their glow, bent-double, plastic-wrapped, alone and in company, on trains, heads bowed, stepping into oncoming traffic, present in a different distant moment making plans for lives that are passing us by, missing the present like a train that always leaves too early. The things that don’t mean to hurt us we will use to injure ourselves. Not understanding the extent of our self-harm. Not asking ourselves a question perhaps we need to.

How much is gained. How much is lost.