Weekend 21st – 22nd March

The whites of the doctor’s eyes double in size as he says:

You need to get out of this room right now.

I grab my rucksack and bolt out of the surgery. A minute earlier while assuring him it was nothing like the dry Corona cough I’d read about, I mention all the symptoms of a common cold have been afflicting me for a fortnight. Once outside on the street he calls me. We still don’t know what the exact symptoms of this virus are. You could easily be carrying it without knowing. My shame surprises me.

Over the weekend the streets in central are quiet but not ghostly. It is brilliantly sunny and strange for it. As if with everything going on you can’t enjoy it as much, but also savour it more than ever. As if you always took the world for granted and now it’s off and you’re stealing a last look.

Sores are appearing on my right hand from all the scrubbing. We spend most of the day in the flat. Getting outside restores us but inside we are safe and out there is where the virus lives, so we are tentative. Matilda and I walk along the canal in the fading light. The sun is low and the temperature drops fast, an eeriness marks the evening.

My mother keeps texting, encouraging us to come up to the countryside. My father emails to say it is not ridiculous that we have abandoned him in the Pampa… it is a sin. We decide to leave London the following day by bicycle. Nothing exposes a 36 year old without a driving license more than a pandemic.

Monday 23rd March

335 deaths. Another sun-blanched day. A doctor friend of Matilda’s says if we’re careful it isn’t so dangerous so we decide on a taxi. Matilda is terrified of infecting my mother. At midday I run around the marshes and stop by the honeysuckle bush, a single flower from last June is still hanging on giving off its faint sweetness.

I make sure to wipe the sweat from my brow with my sleeve, then with a different part of my sleeve, until I run out of sleeve, then with my top, and stop, a sweaty mass of uncertainty, still not understanding if I can infect myself or if I’m being a tool. I leg it home.

We pack bags with what we might need for who knows how long. I worry my plants will die. Away from the city we fly. As we cross into the Vale of Aylesbury Boris enforces the lockdown.

Tuesday 24th

The red kite hovers on the wind outside the window, the daffodils dance, for the first time we hear no sirens in the night. Yesterday feels like 72 hours ago says the radio woman. Each morning brings a tsunami of media. I’ve had enough of it, says my mother. But she is happy to have us. She explains some house rules from 2 metres away as we walk in the garden.

I shout to my brother out of a window from across the yard, where he and Victoria and Mary are living. We have a family kick about and I do 43 kick ups. In London it stared us in the face every day but out here it is easier to forget somehow, which feels funny but not haha funny.

On the radio the man’s voice cracks, his dog-walking business is all but lost. An author says he has been self-isolating for 28 years and can’t tell the difference. Trump bellows out a tweet. WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF. I wonder what it is we will be cured of. A celestial thumb holds down the command key and hits R.

Wednesday 25th

465 deaths.

In the afternoon I run the circuit.

It is calm. I feel half the world away. The knuckles on my right hand are parched from the soap and two are bloodied. I run along North Marston road past the copse of trees on the outskirts of the village where all those years ago the man stopped me.

He waved me over with his hand and put his finger to his lips. From far above came the repetitive thud of something against the wood. I built a house for it once. It came back, he whispered. For a few minutes we stood there together in silence with our necks craned up, listening to the sound echo through the trees. The man didn’t look at me once. When I finally said goodbye he said nothing, just remained stock still, staring up through the branches. As if I had never been there.

Thursday 26th

578 deaths. The Oving village newsletter quotes Maya Angelou: A bird does not sing because it has an answer, it sings because it has a song. At 8pm the nation beat on frying pans and hoot and clap together in song to the Health Service.

In the house we shout to one another through closed doors and adhere to specific time-slots in the kitchen. Every appliance and surface and salt shaker is wiped down. To my mother’s chagrin Victoria hits up the local butcher which means another fortnight before she can hold Mary.

In the Pampa my father resigns himself to sit out the quarantine alone. But an ocean is no match for papa, from 7,000 miles away he makes his presence felt. Tout comprendre c’est tout pardonner as he loves to say. I suppose he feels alone and trapped and has a strange way of showing it.

Friday 27th

At some point this week Italy becomes the global centre of the pandemic. At some point this week the numbers become too strange to fathom. Deer wander through the subway of a Japanese city. Mallorcan police serenade the public with guitars. For five days England is in the stranglehold of uncut sunshine. Mary doesn’t understand why I won’t play Velcroball with her. This morning in Oving for the first time an ambulance siren pierces the birdsong.

*

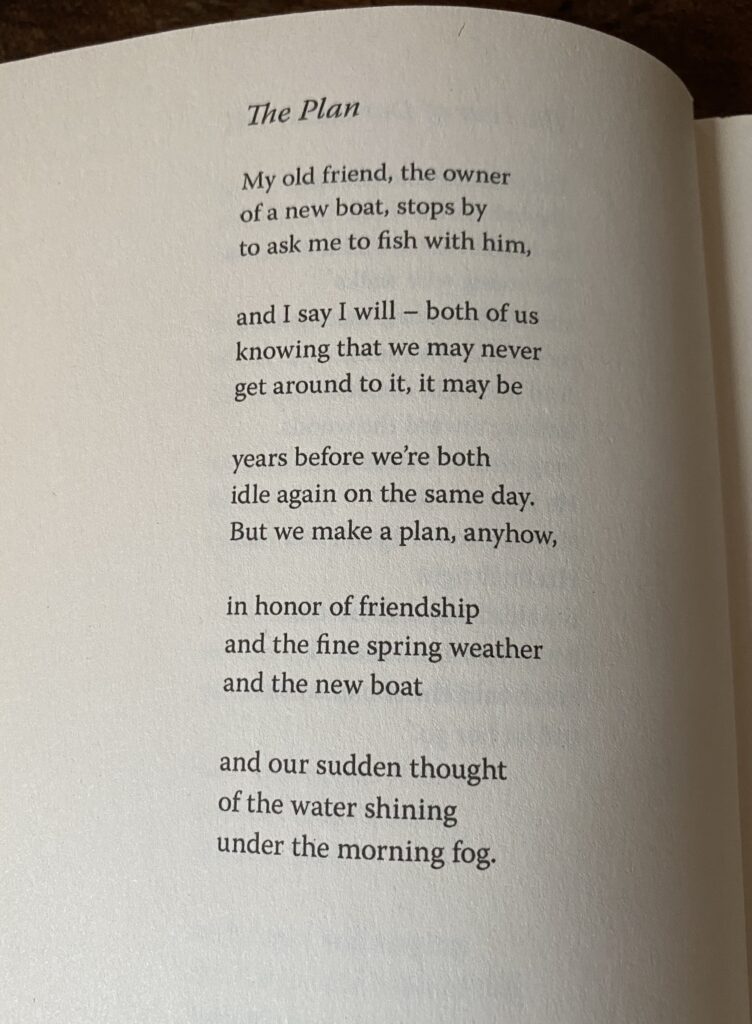

I oscillate over the weekend between dread and unknowing and fight with the point of writing. I worry about not seeing my father again. The clocks go forward. My friend Greg sends me a Wendell Berry poem called The Plan and I think it is the best thing I read all week.