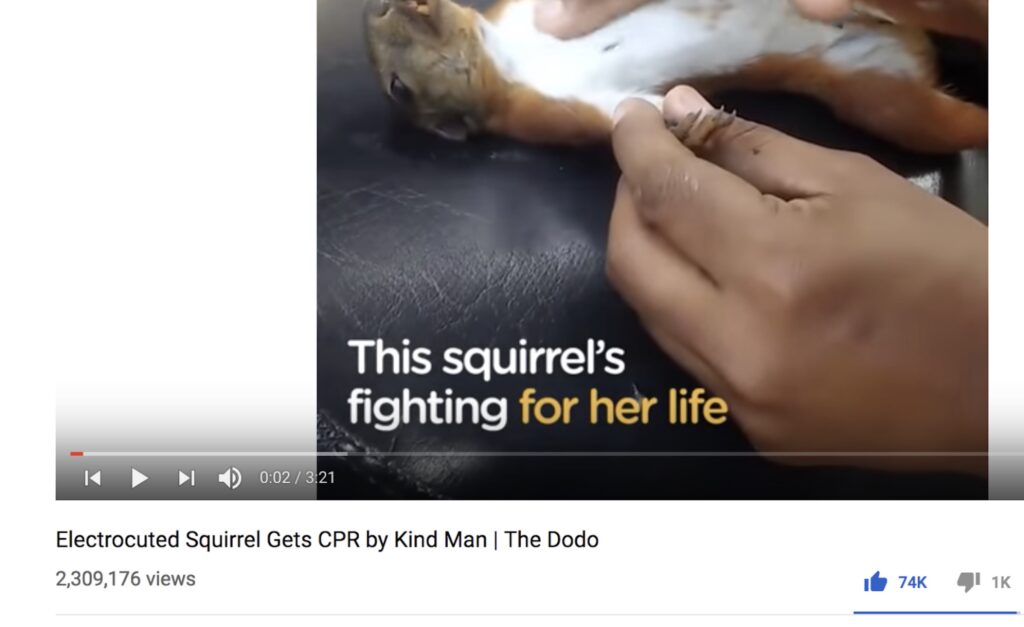

The wild elephants turn back to salute the men who have saved their baby elephant from the ditch. They raise their trunks aloft with wondrous grace in a moment between man and beast. I don’t blink, hardly twitch. Lit by the glow of the laptop screen, my face shows no flicker of emotion. The video finishes and the next one begins to load. Electrocuted squirrel gets CPR by kind man. Unbeknown to me, the daylight has faded across to the other side of the earth and I am in darkness. I am lying on my bed in the fetal position, as I have been for three hours straight…

… watching YouTube.

I don’t know how long me and YouTube has been a problem.

The first chapters of all addictions are written in the pen of innocence. Mine started in the same way all others must, with a joy unforeseen. A music video with a new friend behind the sofa at some party one unending night of summer. An email in my inbox linking a highlight reel of Messi’s greatest dribbles, coming in off the right wing, scything through tackles like water.

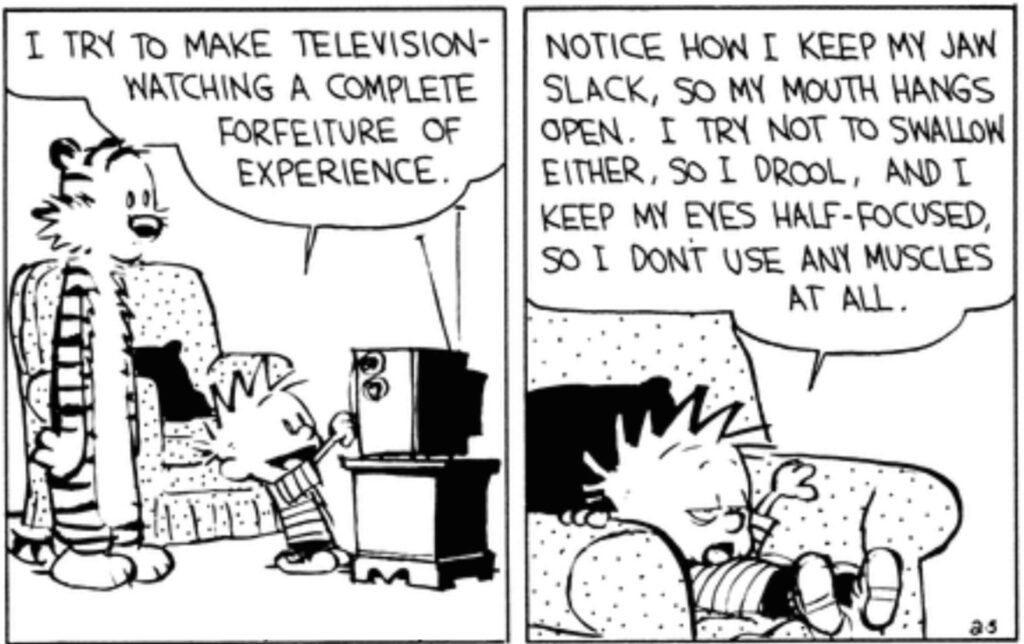

If I’m scrupulous I admit it started long before that, pre-internet. My parents didn’t let us watch much television. My answer to this depravation it seems, whenever they were away, was to flick through the channels like a drone, hoping of landing on something which gripped my attention for any longer than the spilt second it took for me to glean, ignore, and plough onwards. Alone, I never watched anything for longer than two minutes.

Years later I saw this interview with the writer David Foster Wallace, and it hit me deep.

Wallace fought a depression for most of his adult life that he succumbed to in 2008, aged 46. He suffered with different types of addictions, but said his primary addiction, as unsexy as it sounded, was to television. He was so afraid of watching it he couldn’t have a tv in his house. Hearing this for the first time opened my mind to the idea that the YouTube thing, as it moved silently along the forest floor of my impulses like a fox on his feet of silk, demanded a seriousness I was unwilling to give it.

Every addiction balances on the fulcrum of denial. The decline before the fall was coloured by a lake of awareness. I was unaware the habits I was slowly slipping into weren’t okay. At first it was just weekends. I was single and lived alone, if I woke up hungover it would be easy for me to turn my back on anything productive or social. One weekend I became fascinated by the internal politicking of the WTA tennis tour. Another weekend it was American High School track and field. A man in Pennsylvania fashioned knives out of rusted wrenches. I was in.

There were times when I wouldn’t communicate with anyone all day. It was isolationist, and repetitive, and hypnotic, I would sit entranced, swelling my command of thoroughly useless information as YouTube gently weaved its spell on me, drawing me down deeper and deeper into its pixelated underworld. As one video finished another one on a similar topic loaded, suckering me in for another five or ten minutes. Half hours became hours became half-days. And outside my window the world whizzed on.

*

A lot of people don’t know how to watch YouTube.

I wouldn’t know what to look for, my friend Milly once told me. Talking dog’s unique bark helps him get adopted is good, I thought. I shrugged and said nothing. A system of recommendations based on previously viewed videos appear as if by magic at the top of your screen, which means the table is always laid. If you’ve been watching videos on the Anunnaki and ancient alien space-travelling civilizations, it’s going to show you more of where you last left off when you next click on. Even when I wiped my recommendations, the subjects my dark side needed feeding on were etched already in my memory.

All that was left was to type them into the search bar.

To be addicted is to be completely at the whim of your impulses. Tick. To realise you are no longer in control of your decisions. Tick. To be aware that the behaviours you are undergoing are harmful to you, tick, are making you unhappy, tick, and in spite of this to repeat them nonetheless. Tick. I was losing control over my ability to not watch youtube, and in doing so I was losing days of my life I wasn’t going to get back. But still somehow I didn’t pay it the seriousness it deserved.

I did take a knife to my internet connection three times.

*

In 2007, back when I was at art school we were given a brief to go and do some Guerilla Marketing. To take something about the world we were upset about and use the urban landscape around us to be disruptive in. The idea was to give people a message we think they needed. I stayed up til 2am cutting out a set of stencils with a Stanley knife, I loaded up my backpack with spray paints and cycled through the darkness of the Witching Hour to go and leave my mark. The next day I went back as a sleep-deprived passer-by to watch people interact with it.

*

From just weekends, my YouTube habit morphed into week nights and then during the day. Work deadlines were affected. Spending a lot of time alone in front of my computer, the slightest sniff of procrastination would send me spiralling into the depths and I’d emerge an hour later, all the wiser, constipated by information I didn’t need to know.

Eating disorders are supposed to be so difficult because mealtimes mean the lion is let out of the cage three times a day. When most of our time is spent looking at screens, internet addiction means the lion never has a cage to begin with. It comes down to willpower and impulse control. Both of which are low on my list of virtues. Not having a smartphone or on any social media granted me a certain type of freedom, but it also meant all my wrath and self-loathing was concentrated into one place. Alone and in front of my laptop, I would make up for lost time.

I was acting out, YouYube was my drug of choice.

*

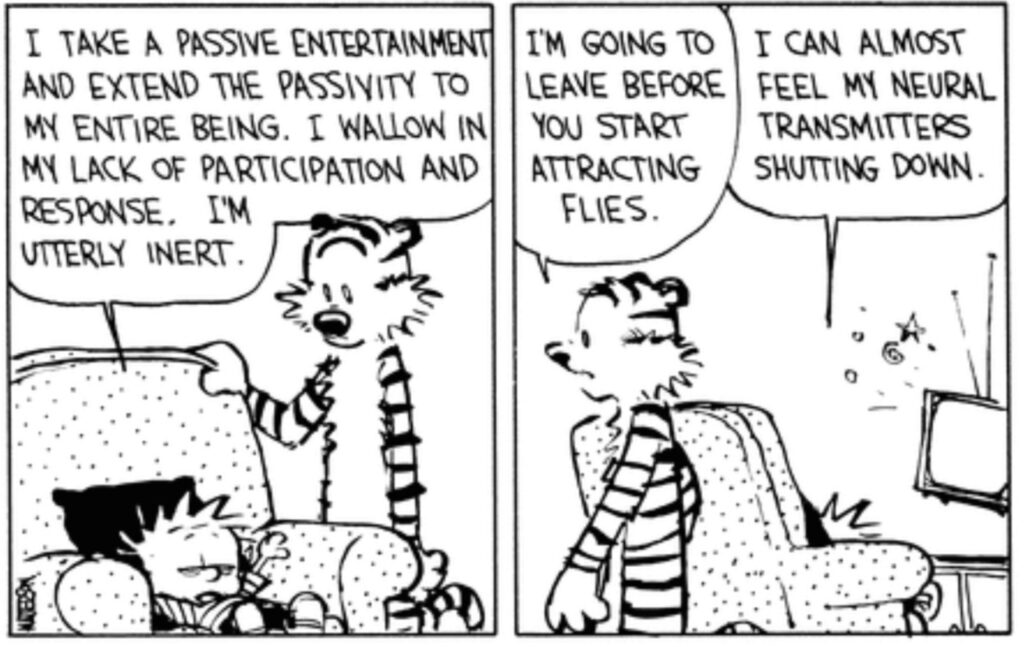

We’re going have to develop some real machinery inside our guts to turn off pure unalloyed pleasure. Because the technology is just going to get better and better, and it’s going to get easier and easier, and more convenient and more pleasurable to sit alone, with images on a screen given to us by people who do not love us but want our money. And that’s fine in low doses. But if it’s the basic main-staple of our diet, and I say this in a very meaningful way, we’re going to die.

David Foster Wallace

*

The strangest thing about the YouTube thing is this.

When I was acting out, I couldn’t watch anything that i enjoyed. I couldn’t sit down and watch an hour long documentary about wine-making or the Pyramids of Giza. That was the truly pathological nature of it. I had to watch short clips, back to back to back to back, about absolutely nothing. 95% of everything I watched in the grips of my youtube habit didn’t improve my life in any way. It was the American History X moment over and over again. Has anything you have done, made your life better.

This is all quite funny. The ridiculousness of it all, it’s laughable. But maybe I laugh to keep from crying. Because if you take away the politics of the WTA and fashioning knives from wrenches and elephants raising their trunks aloft to thank the men for saving their baby elephant from a ditch, what you’re left with is somebody alone in their flat, in the dark, willing unhappiness on themselves. In ignorance of the life going on outside their window they are walling themselves up against, in defiance of the light from the phone on the table beside them that is ringing and they won’t answer.

Some poisons go to work more slowly than others. They hide in plain sight all around us, masquerading as tools to make our lives more accessible, more comfortable and more immediate. One day we wake up and they’ve wormed their way inside our minds, ossifying our imaginations, crowding our every moment. And before we know it without them we can’t breathe.

I’ve got this, we tell ourselves, but they’ve got us.

Wallace described the moment when we finally find ourselves alone, and the dread that comes with that, that comes to us when we have to be quiet. When you walk into public spaces these days, there is always music playing. It seems significant that we don’t want things to be quiet anymore, he said. And this is happening now more than ever, when the purpose of our lives is immediate gratification and getting things for ourselves, we are moving moving moving, all the time moving.

At the same time there is another part of us that is the opposite. That is hungry for silence and quiet, and thinking very hard about the same thing for maybe half an hour or more, rather than just thirty seconds. Of standing and looking at the branches of a tree, or listening to the birds singing. And this part of us doesn’t get fed.

And what happens is this thing makes itself felt in our bodies, as a kind of dread, deep inside us. Every year it becomes more and more difficult to ask people to read a book, or to listen to a complex piece of music that takes work to understand. Because now in computer and internet culture everything is so fast. And the faster things go, the more we feed that part of ourselves that needs something immediate, that needs instant stimulation, and we don’t feed the part of ourselves that needs quiet.

The part of us that can live in quiet.

*

Brick Lane, 2007