They didn’t know it but I’d been recording them for a while.

Hiding mics under cushions, behind the marmalade, in the sleeve of my coat. While they mused on dead poets or fine places for murder mysteries, family history and the silhouettes of trees. Whenever they busted me they’d go ape. This is voyeurism they’d cry. I’m immortalising you, I’d shout back. It made for great listening, when they weren’t around, they wouldn’t always be.

I could crack a can, press play, get a piece of them.

There was a method to this espionage. What motivated me was a thought, that not thinking hard about los padres perhaps not being around, what a world like that might look like, before the day something did actually go south, and the news coming in, a text of some sort, the type that blindsides you on some idle Tuesday, would be like going into an exam room having done no revision.

With eight decades and change of fine lunches in him, Pops was beginning to creak at the hinges, crankier than ever, his impenetrable memory was showing weak spots. And as if overnight, he began to lose the use of his right hand and foot, could no longer write, could no longer type, dragged a leg behind him. We all got worried. They made a mad dash to BA for a brain scan. We waited.

When we’re young the raised eyebrow Home Alone moment seems ideal.

I made my family disappear.

But when it starts happening, you start realising how quickly you’d like them to not disappear too much. More friends than I can count on two hands had recently been through this pain, and pops’ malaise was a clearing your throat moment coming into rearview.

*

Parents can break balls, no surprises there.

What would I miss, I wondered.

Hands.

I’d miss the smoothness of hers, that grabbed mine and dropped them with a pat after half a minute because she wasn’t brought up Latin. The tinkle of mamama’s bracelet on her wrist. Her jumpers, a mother’s smell. How she said oh do get on when I was being a simp. Her non-pushover kindness. Watching her on the sofa all zizzed out. I could live without her tech quandaries or running film commentaries. Most of all I’d miss never knowing what the hell was going on in her head. Very mysterious lady my mother.

Him.

I’d miss his solid granite-like fingers fused at the joint. Thumbwar. Asking him inane shit just to get my favourite reaction. Pero vos estas loco. The way he stopped mid-walk for eternal minutes to make some point. His bottomless pit of knowledge. The stupidly expensive wine he ordered with a what the hell else are we here for look. His madman giggles alone to himself having breakfast. An ability to catch immediately the nuance of your thought. I could leave his rage and high maintenance. But his singing at table, his half stare lost in some thought, some passage in a dusty novel or what was for first course, I’d miss that.

It wasn’t my father faltering that made me write this. I’d watched friends go through real shitters and wanted to help, I’d learnt things and wanted to iron them out, see if there was anything I could spin to make sense of the nonsensical. Life is a great surprise, said Nabokov. I don’t see why death should not be an ever greater one.

*

Everyone’s favourite Austrian grandpa has his gameface on.

Surely death can’t be like birth, says the interviewer, if it’s an end.

Yes if it’s an end, says Jung, and there we are not quite certain.

There are peculiar faculties of the human psyche that aren’t confined to space and time. You can have dreams or visions of the future. You can see around corners. Only ignorance denies these facts. It’s quite evident that they do exist, and have existed always.

So we grieve.

We grieve life itself. We grieve separation from youth and beauty, we grieve past lovers, the hedonism of weekends with no commitments, things we can’t get back. The photo stared down at me every time I brushed my teeth. The one I put up there thinking it would inspire me, make sure I didn’t let the little guy down.

How could I let him down. Even back then, he was me now. Just as I now, was him then. He’s inside me, I’m inside him, we’re the same. Some days I miss her. But where is the separation exactly. Everyone you’ve ever met, been brave enough to love, is inside you. Every morning, afternoon, late night conversation, every row, every lol, every half glance. How could you be separated.

Surrounded by his followers at his bedside, the dying monk laughs. Why do you cry. Where could I go. If we zoom out we are all part of the same essence, the same grand process, separate pages bound in the same book. Moana, on the cusp of her great journey, unable to leave her dying grandmother behind, goes to her bedside.

Scene killed me.

There is nowhere you could go that I won’t be with you.

*

The tribes of the Amazon say the same thing, they know it intuitively, in the west you have severed your connection to spirit. The Hindus have their reincarnation. Encouraged in their culture rather than dismissed, Indian children remember past lives until their prefrontal cortex develops. In touch with the endless cycle of death and rebirth.

A mountain, described by the Buddha, six miles high six miles wide and six miles long, where every hundred years a bird flies over with a silk scarf in its beak, running it over the mountain once. The length of time it takes the scarf to wear away the mountain is the length of time we have been on this cycle.

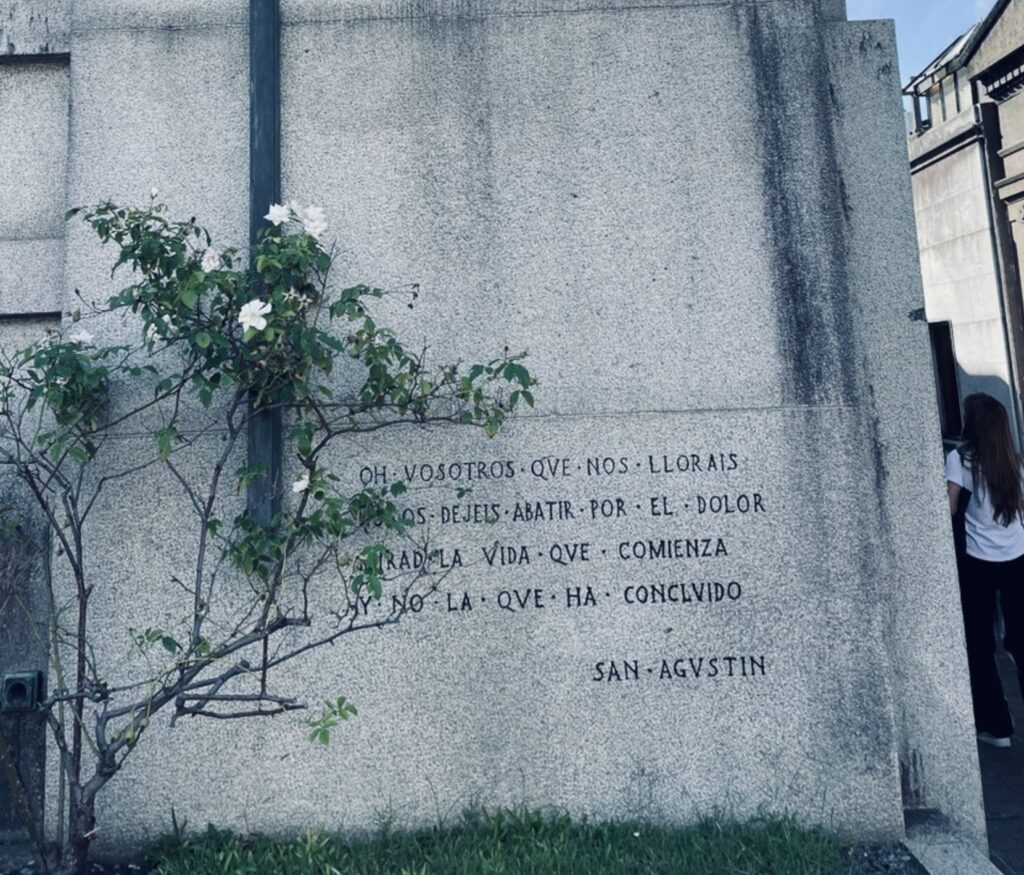

Walking through the Recoleta with Clara searching for our grandparents’ tomb, we take separate avenues. Rounding another corner in the maze, I see on the wall a line from St Agustin.

Oh you who cry for us

Do not let yourselves be cast down by your grief

Watch for the life that begins

Not that which has come to an end

Sat there with a friend in the pub, I explained the things I was trying to understand. She looked sadly into the middle distance, thinking of her pops. You’re right he did have a good one, he wasn’t that young I suppose. I know it sounds woo-woo I said, but apparently this stuff might be actually going down. Don’t be silly I love your spiritual stuff, she replied.

We don’t understand the world very well. What of stories of NDEs, near death experiences, accounts of tunnels and light and immense peace. 21 grams. The weight of the human soul. Stories of past-life regressions. Mysterious clues that point towards a continuation. If it is an end, Jung had said. And there we are not quite certain.

When Jules’ dad died they buried some of his ashes with a sapling in the garden. Once inside they looked out and saw Xav’s dog Vaya sitting there, as she had been for the last ten minutes on guard, staring unmoving.

Tell me where you’ll be, my cousin Clara implored my uncle when he was very ill. Communicate with me, find me. Francisco her brother kept his ashes in the living room, spoke to him, asked him things. I chatted to him about something yesterday, he told me in a voicenote.

Sat there alone in my flat I frowned. How does he know this stuff, I couldn’t figure it out. It was a recording from 1985, Ram Dass was mid-flow.

When you’ve entered into real love with another human being, there is huge attachment to the loved one, they are your connection to that feeling of love. So when they die the loss is felt so intensely, you try to hold and grab onto the person you knew.

My suspicion, because their karma was very involved with you, is that when they leave their body often they stay in a certain space in order to be there for you. Once a grieving process runs its course, and that can take time, years, there begin to be moments where there is a little space. Where you have opened to the grief, and can be quiet in a moment, and feel the sense of being back in the love, in the presence of the whole thing again. Not in the presence of the person, but in the presence of the essence the two of you had.

But because the grieving is so loud, and you are busy missing the person, you want them the way they were, to talk with them, to have them talk back to you, you don’t get quiet enough to hear that the thing that was the essence of it, hasn’t gone anywhere. It is still right there, all this time. And when you find this moment of peace, you get what you wanted, but not the way you thought you were going to have it.

*

This is quite amazing.

*

Grief is a thing with feathers, grief is a storm we weather.

On the rock in the vast nothingness we continue the spin-cycle. We look up at the moon. As the ancients did. How long have we been doing this. The bird moves the scarf over the mountainside, brushing across it gently. See you in a hundred years. What is even going on. The grand miracle of everything.

It seems to me to be as close as we can come to an armour, to protect us against the full force of the blow. How much we feel is how much we love. In our hearts and minds we keep them there, alive through love. They live in us.

There is nowhere you could go that I won’t be with you.

This is no answer, an attempt at a balm maybe. A way we might come closer to understanding the un-understandable. If we knew what was going to happen, we might care less about the thing in the first place. So it remains a mystery, for us to fumble around in the dark in spite of.

A mate showed me a poem, by an Alaskan Native American called Mary Tallmountain, called No Word For Goodbye.

Sokoya, I said, looking through

the net of wrinkles into

wise black pools

of her eyes.

What do you say in Athabascan

when you leave each other?

What is the word

for goodbye?

A shade of feeling rippled

the wind-tanned skin.

Ah, nothing, she said,

watching the river flash.

She looked at me close.

We just say, Tlaa. That means,

See you.

We never leave each other.

When does your mouth

say goodbye to your heart?

She touched me light

as a bluebell.

You forget when you leave us;

you’re so small then.

We don’t use that word.

We always think you’re coming back,

but if you don’t,

we’ll see you some place else.

You understand.

There is no word for goodbye.

*

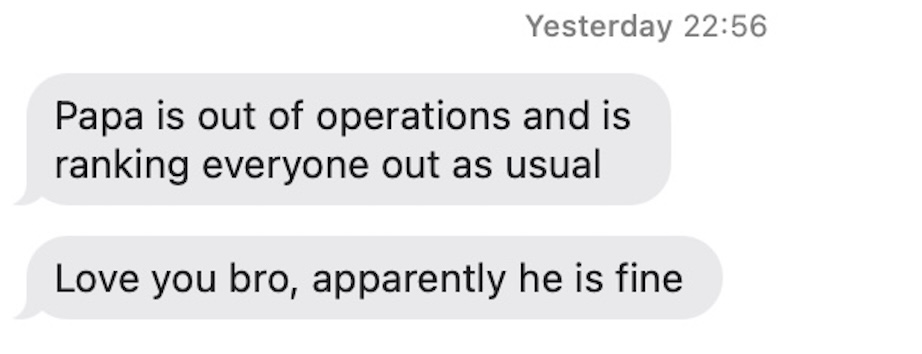

The results from the scan came back.

A blood-clot on the brain from an accident months ago, was pushing the thing to one side away from the cranium. This explained the loss of movement in his right hand and leg. They operated, drained it, within twelve hours he was back to some semblance of normal. The whole time I was strangely calm. It surprised me.

My bro texts.

Having fought with two nurses before the sun had risen, down the phone to me this morning talking through his death’s door moment, we spoke of the divine and what awaits, spoke of prayer, things I’d learned, you need to teach me, he said, I will be your disciple, then started barking at me for abandoning him. Yeah, he was back. The dictaphone could wait. Not forever, but a while.

*

Where are they.

Inside us, I think.

When does your mouth say goodbye to your heart.

Separate pages bound in the same book.

A clumsy attempt to tie some things together.

How to deal with great pain, I wonder, pain many had felt, were feeling, a pain we would all feel. Maybe to register we ever had anything to start with. What are the chances, all things considered. And we will wonder not where are they, but wow, how come I got to spend some time with them at all.