Monday October 19th was a day like no other. Similar you could say, but uniquely different. As the morning news filtered onto the interfaces lighting up the screens and dinging the notifications, the nation roused itself to smell the coffee.

Covid vaccines were forecast for the end of the year. Trump’s health was improving. Michael Gove had declared the door to the Brexit trade deal ‘ajar’, and Britney had set pulses racing with a sexy dance on instagram in a red halter top.

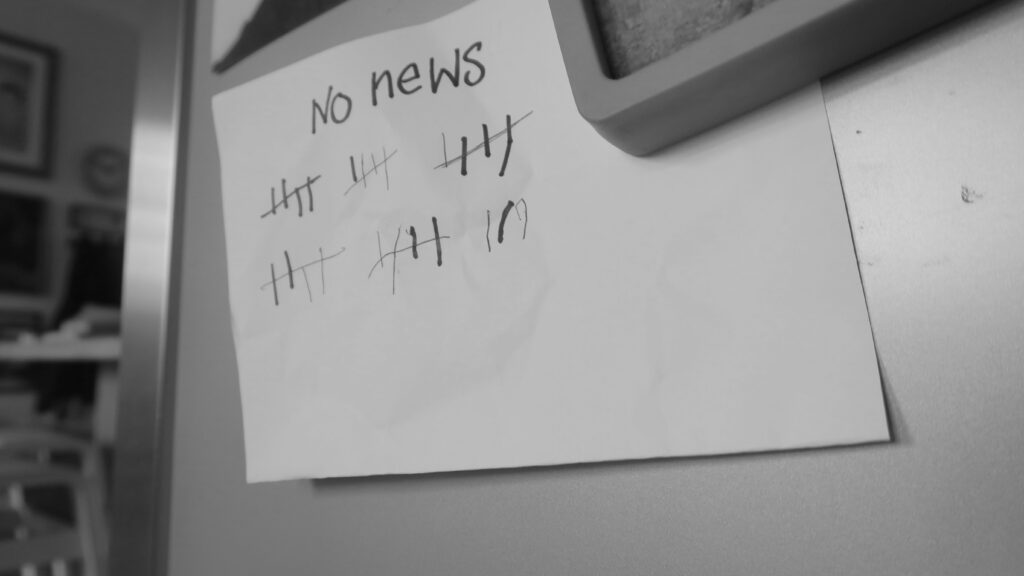

In the shower around 7.19am, I made the decision to stop watching listening or clicking on any news for a month. The Stoic deprivation thing was part of it. But it was more that I was going mad. My life had become a metronomic clickfest of newsfeed incontinence relieved by snatches of sleeping and eating.

BBC News Guardian FT BBC Sport ESPN Grazia YouTube BBC News Guardian FT Heat BBC Spo… Refresh consume excrete refresh consume excrete.

It was another thing too. The day before, I’d gone online and noticed every one of the two dozen articles on the homepage I was blinking at was about something terrible. Death, crime, poverty, scandal, corruption, racism, climate catastrophe, deadly virus.

Hand an extraterrestrial the morning paper and it’d be like these cats have fucked this place up good I’m out. It was the grimness of the headlines more than anything that made me stop to wonder if this relentless checking and informing and updating was doing my mood any favours at all.

In his book Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker writes how contrary to what the media would have us believe, progress throughout the world in the last 150 years has been close to miraculous. Deaths in war have plummeted, extreme poverty has halved in three decades, the world has seen a mass decrease in starvation, domestic violence and child abuse are down, life expectancy is way up, there is 90% global literacy rate in under 25’s, and the world is a safer place.

But journalism tends to cover what goes wrong rather than what goes right, what happens rather than what doesn’t. Bad things, Pinker points out, are sudden and dramatic and occur on an idle Tuesday in May. An attack, a riot, a bomb blast. Good things are things that don’t happen, such as children not starving, terrorism not taking place, nations not being at war.

Knowing full well that humans are evolutionarily tilted towards negative information, the mainstream media goes fishing. So in ignorance of all the good in the world, we read of Sarin gas attacks and police brutality, spiralling infection rates and Kim Kardashian’s butt-reduction, now brought to us in real-time by a new army of video journalists, basically anyone with a smartphone.

I stepped out of the shower, somewhat purified, and got busy. I deleted the news apps on my tablet and set up some site blockers on my computer. Not owning a smartphone meant time in the street was free from temptation.

Leaving the flat that morning I felt the lightness that comes with the instinct of being kind to oneself. Outside all was as it had been. The traffic lurched and gargled, the last leaves trembled, the lollypop man on the crossing by the school smiled.

My first encounters were positive. Friends nodded in understanding, said they’d thought of doing the same, the lady at the checkout gave a look of earnest commiseration. It’s all the same so dreary day after day yer doin a good thing.

But mid-morning at my desk when the site-blockers barred my way I was taken aback. What the hell was I supposed to do, how was I going to know things. The infection-rate. Had London gone into Tier 3. Was Donald on the mend. Keeping up to speed could be deemed more critical now, than say, on Jubilee Weekend.

What if I emerged from my flat 28 days later and the streets were empty, the shops boarded up, just a harsh wind beneath a birdless sky, and the world was unrecognisbale. What if we were top of the league with two games in hand.

I began to sniff out clues for signs of the pandemic, the sirens in the air, the number of masks, the degree of crestfallen countenances. I glimpsed a news board one night cycling through central with the words Isis in Vienna written large on it. In the back of a taxi I heard something muffled about Macron addressing his people. From the bowels of my laptop a video emerged of a concerned-looking Boris behind his wooden lectern and I closed it down immeditely.

I perfected an appropriate level of concern facial expression, a grin and bear it brow-furrow, and a shrug of humorous resignation, hoping that would cover all the bases. So if I got chatting to a stranger they wouldn’t clock I had absolutely no fucking idea what they were on about.

The churning news cycle was a conversation I had been left out of and I felt dumber for it. But also calmer, like I was the guardian of my own secret, of the things going on around me. Instead of drawing in on myself, I felt pushed outward. Like a great gulp of mountain air.

I noticed time more, there were now pauses between things. I could break from a task without going all bbcsporguardiayoutubeholebleughh, I would sit there, stare in the fridge, do some jigsaw. My brain began to refocus, my attention span spread its wings.

Outside there were sounds, strange shifts in air currents, winter’s creep, the harsh brick of St John’s against my hand. I found allies in the things headlines meant nothing to, the building cat, the enormous planes of London fields, the wide-eyes staring out from prams. I began to feel a little as they were always, present in my surroundings.

On the off-chance I might leave the house one day and get tased and airlifted to a bunker by the World Police, I told my mother to text if Boris and his stooges went full-Wuhan. I forgot about the US election entirely. I was on a roll. What else could I give up that required being on my own in the flat with decent wifi.

Two and a half weeks in, the country went into nationwide lockdown. The same day the election results came in. I’d gone down to Devon with a friend, a US politics obsessive. As he relayed the headlines from his smartphone in real-time, I heard an exotic language that needed careful enunciating back to me. Jow-Bye-Dun you say. But a short sharp hit of news was thrilling. I felt part of the crew again.

Was it unethical, was it my duty to keep informed. If news and politics were part of the culture I lived in and I wasn’t engaging in that culture, was I abusing the freedom I took for granted to live in a democracy. What about the men and women affected by job losses and insufficient furloughs, was my no-news experiment mocking them.

When every government decision had a direct impact on mortgage payments, covering rent and buying food, was taking time off from the headlines nothing more than proof of privilege. Or would the world spin on regardless, whether I kept up to date or not.

With all the fun happening the other side of some forcefield, I began to relish my separation. It wasn’t that I’d found something new, more that I’d got back something I’d lost. I was a 90s kid with a pre-internet brain and I was unlearning habits that were so normalised I’d stopped noticing how unbelievably weird they were.

It turned out that this compulsion that had swallowed up two hours of my day, easy, I didn’t miss at all. The moments that filled me up I still had access to, an autumn walk, a book’s depth, a talk with a friend. I literally felt cleaner, and understood what the word detox implied. The removal of some poison.

With only the world in front of my face for company, I decided to write my own headlines. I smiled at everyone like a moron, even through a mask, held-up supermarket checkouts with platitudes, sprained my elbow holding doors open, fist-bumped the lollypop man, left a tin of biscuits for the dry-cleaner, engaged in pretty much every tiny human interaction I could, and saw goodness come my way.

Eventually it came around.

Twenty seven days in, on the eve of my reinitiation, I felt twitchy. Had Trump died. Were Tottenham top of the league. Was the pandemic now a scamdemic, was everything still a mess. I deactivated the site blockers and began to click and refresh and click some more, and somehow.. nothing had changed at all.

It was all the same.

A new president, the pandemic still there or thereabouts, Spurs second on goal difference. Nothing much had happened, at all. Not really. It could’ve been yesterday. Just ever-changing details in an unrelenting cycle destined to endlessly repeat itself.

I’d been here before. I found myself very aware of how this was merely the latest iteration of a sequence which would change tomorrow and the day after and if I checked now or next week it wouldn’t change the core of me. I didn’t have to know. I had stepped off the edge of something.

Straight away the headlines brought a sinking feeling, and I picked up a book, ashamed of my denial, dimly aware it would be impossible to keep ignoring the news, and wary of the slow-spiral that would inevitably lead me back to where I’d started, a lump of media-gorged non-attention.

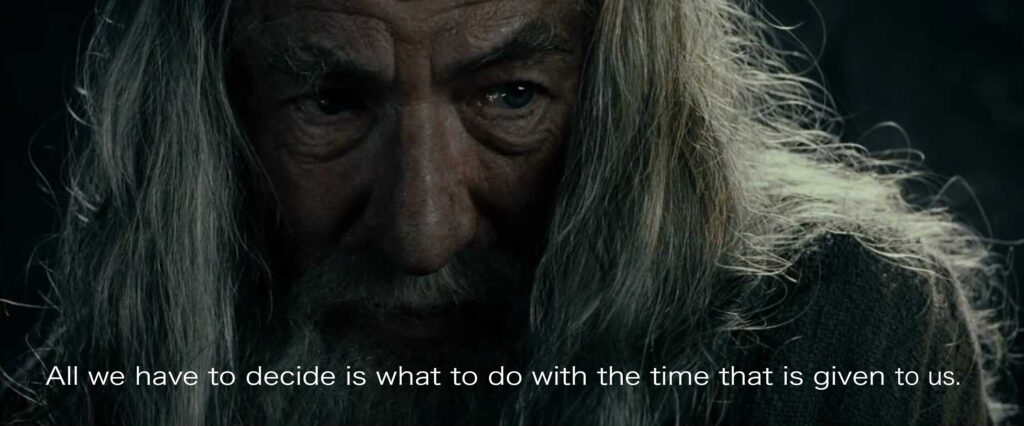

Sitting with my feet up one night watching The Fellowship Of The Ring, an answer came. Exhausted and emotional, Frodo looks into the foreboding dark of Moria and sighs. I wish the ring had never come to me. I wish none of this had happened. Turning, Gandalf fixes his eyes kindly on the little hobbit and murmurs. So do all who live to see such times.

But that is not for us to decide.

The news cycle was the stark evidence of a suffering world. 2020 was a year like no other. I wish none of this had happened. So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for us to decide. The news was going to keep happening whether I read about it or not. Pretending it didn’t exist wasn’t the answer, and relentlessly checking it wasn’t either.

There was another news cycle going on all around me that the media couldn’t report on, tiny miracles beyond the pixelated glare bouncing off my retina that required my attention. The myriad pockets of time in my day, the little windows of pause. How would I spend them, what would I make of them. How would I remember them. All I had to decide was what to do with the time that was given to me.